Foreword

This article is the fourth installment in a series dedicated to decrypting the new era of great power politics through the structural lens of Global Value Chains (GVCs). The analysis that follows, which turns the spotlight on the United States, finds its primary inspiration in the prescient work of Vaclav Smil. His 2014 book, Made in the USA: The Rise and Retreat of American Manufacturing, offered a powerful and enduringly relevant framework for understanding a nation’s geopolitical trajectory by examining the health of its industrial base. The steady hollowing-out of American manufacturing, Smil argued, was not merely an economic trend, but a profound strategic vulnerability in the making.

Recent events have only added credence to this vision. This analysis seeks to adapt and extend Smil’s core thesis to the central geoeconomic contest of our time: the systemic rivalry between the United States and China. This exploration is further strengthened by the insights of thinkers like Michael Pettis, whose work illuminates the deep macroeconomic paradoxes that constrain American industrial policy, and Wang Huning, whose early diagnosis of America’s internal cultural and societal fractures has proven remarkably insightful. Underlying this entire series, however, is the inescapable logic of great power competition, a reality powerfully articulated by the work of John Mearsheimer, whose realist framework provides the essential context for why the struggle over these material assets is not a matter of choice, but of necessity.

Building on these foundations, this article advances a central argument: that the high-technology, “macro techno-industrial ecosystems” we call GVCs are the primary arena of 21st-century power politics. They are the source of economic wealth, military strength, and global influence. As such, in a world defined by the unforgiving logic of the balance of power, control over these ecosystems is not just a commercial prize, but a fundamental strategic imperative, making them the natural and most fiercely contested battleground between the world’s great powers.

Chapter 1: The Industrial Bedrock: Rise, Primacy, and Erosion

How did the United States forge its global primacy in the crucibles of its factories, and how did the subsequent, decades-long dismantling of this industrial bedrock become the nation’s defining strategic vulnerability in the 21st century?

The story of modern American power is not primarily one of ideology or finance, but one of unparalleled industrial might. Its rise from a continental nation to a global superpower was not an accident of geography but a direct consequence of its capacity to produce, innovate, and deploy material goods on a scale the world had never seen. Understanding this history is not an academic exercise; it is essential to grasping the monumental challenge the US now faces as it attempts to reverse a half-century of industrial erosion in a fiercely competitive world. The very foundation of its past glory has become the source of its present anxiety.

1.1 The Forge of a Superpower (1865-1945)

The end of the American Civil War in 1865 unleashed the full, unified potential of a continental-scale economy. In the decades that followed, the United States underwent an industrial transformation of breathtaking speed and scale. This was not merely economic growth; it was the construction of the physical and logistical superstructure of a future global power. The lacing of the continent with steel rails was its first great act. The transcontinental railroads did more than connect coasts; they created a single, vast domestic market, mobilized resources with unprecedented efficiency, and allowed for the projection of centralized power across immense distances. This logistical mastery, powered by an explosion in steel production that soon dwarfed that of Great Britain, was the foundational layer of America’s ascent.

Upon this foundation, a new production philosophy emerged that would give the nation its next decisive advantage: mass production. While others relied on craftsmanship, American industry pioneered a system of standardized parts and assembly-line efficiency—often termed Fordism—that could churn out complex goods at an astonishing rate. This wasn’t just about making affordable cars; it was about perfecting a system of organization and output that could be applied to anything. This industrial model created a virtuous cycle: high production volumes led to higher wages, which in turn fueled a mass consumer market, further driving industrial expansion. By the early 20th century, the United States was no longer just a rising economy; it was a completely new kind of industrial organism, possessing a productive capacity that no European rival could match.

The ultimate test and proof of this industrial power came with the Second World War. When the United States entered the conflict, it was its factories, not just its armies, that decisively tipped the scales. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s call for the nation to become the “arsenal of democracy” was answered with a flood of matériel that buried the Axis powers. In a few short years, American industry produced hundreds of thousands of aircraft, over 100 aircraft carriers, and millions of military vehicles. This was a war won as much on the factory floors of Detroit and the shipyards of California as on the battlefields of Europe and the Pacific. It was the irrefutable demonstration of a core realist principle: in an era of industrial warfare, the nation with the greatest manufacturing capacity holds a crucial advantage. America’s global leadership was not granted; it was built, welded, and assembled.

1.2 Industrial Primacy and the US-Led Order (1945-1970s)

In the aftermath of WWII, this industrial supremacy was institutionalized as the bedrock of a new global order. The United States, accounting for nearly half of the world’s manufacturing output, was the only major power to emerge from the war with its industrial base intact and supercharged. This economic reality underwrote the entire US-led system. The Bretton Woods agreements, which established the post-war financial order and enshrined the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency, were credible precisely because the dollar was backed by the immense productive capacity of the American economy. The world trusted the dollar because it trusted America’s ability to produce goods.

Throughout the Cold War, US industry was a primary instrument of statecraft. The Marshall Plan was not just a financial aid package; it was a program to rebuild Western Europe with American equipment, machinery, and know-how, binding the continent into a US-centric economic and security bloc. American factories supplied and standardized the arsenals of its NATO allies, creating a level of military-industrial integration that the Soviet bloc could not replicate. The “Made in America” label during this period was more than a mark of quality; it was a symbol of geopolitical alignment and the material strength of the “free world”. This was the zenith of American power—a period where its industrial, financial, and military dominance were fully aligned and mutually reinforcing.

1.3 The Great Unwinding (1970s-Present)

It was from this peak of industrial power that a slow, structural decline began. The 1970s marked a critical inflection point, the moment when the logic that had built America’s primacy began to be deliberately dismantled. A new paradigm took hold in American boardrooms and in Washington, one that prioritized short-term financial efficiency over long-term industrial resilience. The pursuit of higher shareholder returns and lower labor costs began to supersede the strategic logic of maintaining a robust domestic production base. This thinking led to a great migration of capital and manufacturing capacity offshore, a move made possible by the very US-led global security umbrella its industries had helped build.

This process accelerated dramatically with the integration of China into the global economy. The arrangement seemed, for a time, to be a masterstroke of capitalism: American firms would control the high-value “brain” of the GVC—the R&D, design, and branding—while China would provide the low-cost labor and manufacturing “body”. For decades, this symbiosis fueled global growth, provided American consumers with cheap goods, and cemented the dollar’s role as the currency of global trade. Yet, it was a bargain with devastating long-term consequences. The United States was, in effect, systematically training and equipping its future peer competitor.

The hollowing-out of American industry was therefore not merely an economic trend; it was a profound act of strategic self-harm. It severed the vital feedback loop between domestic innovation and manufacturing, eroded the high-wage job base that had anchored social stability, and created critical dependencies on a strategic rival for everything from consumer electronics to essential pharmaceuticals. The very Global Value Chains (GVCs) that had once projected American power were now being used to fuel China’s rise. By the 2020s, the United States awoke to a stark new reality: the industrial foundation upon which its global power was built had been catastrophically weakened, leaving it in a desperate scramble to reclaim what it had willingly given away.

Box 1.1 | The Arc of American Power: From Industrial Might to Financial Hegemony

The ascent of the United States to global superpower status was not an accident of history but a sequential process built on a specific foundation: America first became the world’s undisputed industrial power, and only then leveraged that material strength to architect and dominate the global financial system. Understanding this historical arc—from industrial supremacy, to financial primacy, to the eventual, corrosive divergence between the two—is essential for grasping the source of American power and the roots of its current strategic predicament.

1. The Industrial Foundation (c. 1870-1945)

Long before the U.S. dollar was the world’s currency, American factories were the world’s workshop. Following the Civil War, the U.S. embarked on an industrialization of unparalleled scale and speed, overtaking the British Empire as the leading manufacturing power by the late 19th century. This industrial supremacy, secured by vast domestic resources and geographic insulation from global conflicts, culminated in its role as the “Arsenal of Democracy” in World War II. Its ability to out-produce the Axis powers combined was the decisive factor in the war and the primary springboard for its post-war global leadership.

Table 1: U.S. Share of Global Manufacturing Output, 1870-2023)

| Year | U.S. Share of Global Manufacturing Output (%) |

| 1870 | 23.3% |

| 1913 | 35.8% |

| 1953 | 44.7% |

| 1970 | 28.7% |

| 1990 | 21.4% |

| 2010 | 17.3% |

| 2021 | 15.1% |

| 2023 | 17.2% |

Source : Bairoch (1982), UN, Statista.

2. The Pivot of 1971: Power Politics and the Un-anchoring of the Dollar

It was from this position of overwhelming industrial strength that the U.S. established the dollar-centric Bretton Woods system in 1944. For decades, America’s financial power and industrial might were symbiotic. However, the system came under strain in the late 1960s. The decision to terminate the dollar’s convertibility to gold in 1971 was a pivotal moment, driven by a convergence of crisis and a deliberate act of power politics.

- The Geopolitical Need: The U.S. needed to finance the immense costs of the Vietnam War and its broader Cold War military posture, a task constrained by its finite gold reserves.

- The Strategic Power Play: By severing the link to gold, U.S. policymakers made a calculated bet. In a world with no credible financial competitors, they transformed the dollar from a currency backed by a physical asset into one backed purely by the full faith, credit, and power of the United States itself. This move freed the U.S. from external constraints, cemented its financial hegemony for the next half-century, and created the “permissive structure” for massive global imbalances.

3. The Great Divergence and the Vicious Cycle (Post-1971)

The 1971 decision unlocked the gate, but a new corporate ideology provided the motivation to walk through it. Driven by a neoliberal focus on shareholder value, American corporations made the “deliberate choice” to pursue efficiency by offshoring manufacturing. This unleashed a vicious, self-reinforcing cycle:

- The new fiat dollar system permitted large trade deficits.

- The new corporate ideology motivated companies to move factories overseas, which created these trade deficits.

- The resulting capital flows back into the U.S. financial system strengthened the dollar, making domestic manufacturing even less competitive and providing even more incentive for the next company to offshore.

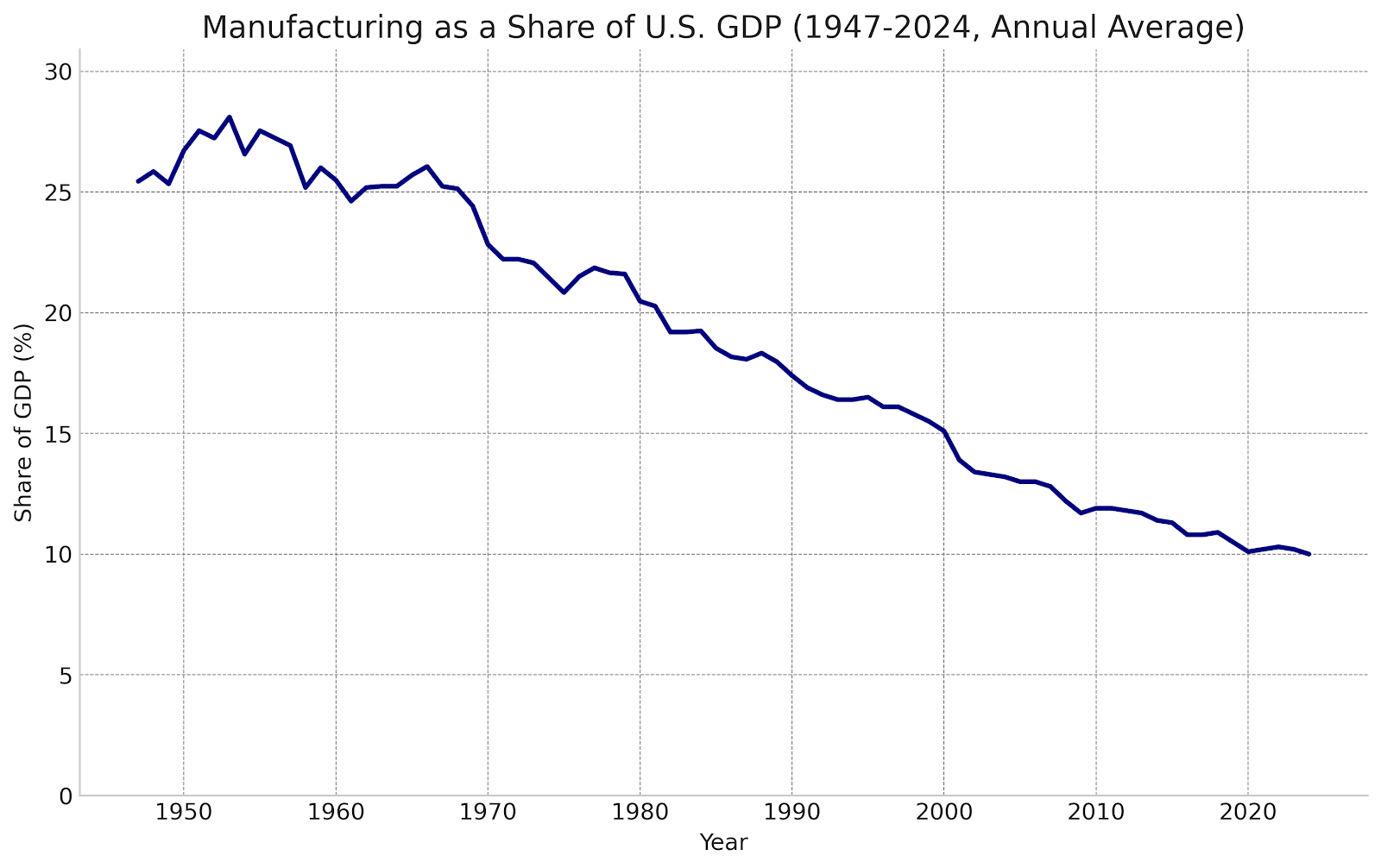

This created the “great divergence” seen below. The chart shows U.S. manufacturing’s share of its own economy beginning a long, steady decline. In contrast, the table shows the dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency, after a period of volatility, becoming entrenched at a dominant level. Financial power had been successfully decoupled from the fate of the domestic industrial base.

Figure 1: U.S. Manufacturing as a Share of GDP (1947-2024)

Source : Bureau of Economic Analysis, Federal Reserve Economic Data.

Table 2 : U.S. Dollar Share of Allocated Reserves (1918-2025)

| Year | U.S. Dollar Share of Allocated Reserves (%) |

| 1918 | 0.6% |

| 1920 | 25% |

| 1928 | 58% |

| 1950 | 33% |

| 1970 | 85% |

| 1980 | 58% |

| 2000 | 71% |

| 2025 | 58% |

Source : International Monetary Fund, Barry Eichengreen (2014).

4. Nuance: Other Factors of U.S. Primacy

A purely industrial or financial explanation for U.S. power is insufficient. This dominance was reinforced by other critical factors, including stable political institutions, deep and innovative capital markets, and the immense global appeal of its “soft power.” These elements helped sustain the dollar’s credibility even as the industrial foundation that first launched it began to erode.

Conclusion: This historical arc reveals the core of America’s modern predicament: its global financial and military primacy was built on an industrial foundation that has since been allowed to systematically erode. In a previous era of unchallenged U.S. hegemony, this divergence between financial power and industrial capacity was considered manageable, or even optimal. However, the return of great power politics and the rise of a peer competitor in China—a state that has masterfully fused its industrial development with its geopolitical ambitions—has transformed this structural weakness into an urgent national security crisis. This new reality forces the central question that this article will explore: Can a nation that has anchored its power in financial dominance for half a century successfully rebuild its industrial base? And can it do so while grappling with the very domestic political fractures and global economic structures that are a direct consequence of its own past choices?

Chapter 2: The GVC Dilemma: Defining the New Battleground

Having forged its global power on a bedrock of industrial might, how does the United States now confront a globalized world where the very architecture of production—the Global Value Chain—has become the central and most fiercely contested battleground for 21st-century primacy?

The answer requires moving beyond simplistic metaphors of “supply chains” and understanding these systems as they truly are: the complex, living ecosystems of national power. The current geoeconomic struggle is not about trade balances in isolation; it is a fight for control over the intricate networks of production, innovation, and logistics that determine which nations will lead and which will follow. For the US, this represents a stark awakening to a battleground it helped create but whose strategic nature it disastrously misjudged for decades.

2.1 From Abstract Chain to Physical Ecosystem

To grasp the stakes of the new great power competition, one must first discard the one-dimensional image of a “chain” and see the system in its full, three-dimensional reality. A Global Value Chain is not a line, but a techno-industrial ecosystem: a dynamic, interwoven network of physical infrastructure, human capital, and intellectual property. It is through the mastery of this entire ecosystem that durable national power is now built. We can dissect this system into three primary layers:

- The Innovation Layer: This is the “brain” of the ecosystem. It comprises the universities, R&D laboratories, venture capital funds, and design centers that generate the foundational ideas, patents, and software that drive modern technology. For decades, the US has been the undisputed leader of this layer.

- The Physical Layer: This is the tangible “body.” It is the sprawling network of factories and industrial clusters; the mines and processing facilities for raw materials; and the logistical arteries of ports, railways, shipping lanes, and undersea cables that move physical goods and data.

- The Human Layer: This is the central nervous system that animates the ecosystem. It is the skilled workforce of engineers, technicians, factory managers, and logistics experts who possess the tacit knowledge and operational experience to translate designs into products and manage complex production processes at scale.

The critical insight, and the one that American policymakers overlooked for a generation, is that manufacturing is the essential nexus where these three layers converge. The factory floor is where abstract ideas from the innovation layer are transformed into tangible, high-value goods by the human layer, utilizing the physical layer. Without a strong domestic manufacturing base, the innovation “brain” becomes detached from the production “body.” Its brilliant ideas are commercialized and scaled elsewhere, the vital human skills of production atrophy, and the nation loses the capacity to physically produce the very technologies it invents.

2.2 The Old Bargain: A Fractured GVC Spectrum

The post-1970s era of globalization was governed by an asymmetric bargain, a strategic wager made by the United States. Confident in its Cold War victory and its seemingly unassailable lead in the “innovation layer,” the US concluded that true power resided exclusively in the “brain.” Manufacturing, by contrast, was increasingly seen as a low-value, commoditized activity—a cost center to be optimized, not a strategic asset to be protected. This logic led to a deliberate fracturing of the GVC spectrum. American corporations, with the full backing of US policy, retained control of the high-margin nodes—IP, finance, branding, and R&D—while systematically offshoring the physical means of production to countries like China.

This arrangement was hailed as a “win-win.” The US enjoyed lower consumer prices, higher corporate profits, and could focus its resources on frontier research. China, in turn, received the capital and employment needed to modernize. But it was a profoundly flawed strategic calculation. By outsourcing its industrial base, the US was not merely outsourcing low-wage jobs; it was outsourcing scale, experience, and the potential for future innovation. It was handing its nascent rival the profits, the immense tacit knowledge of at-scale production, and the manufacturing ecosystems required to eventually build its own world-class “brain.” The US believed it was simply leasing out its factory floor, when in fact it was funding the construction of a rival industrial fortress.

2.3 The Collision: Competitive Re-integration

The current era of all-out geoeconomic competition was triggered when this flawed bargain reached its logical conclusion. China, empowered by its dominance of the GVC’s physical layer, launched a deliberate, state-directed campaign of vertical integration from the bottom up. Its goal was no longer to just be the world’s factory, but to ascend the value spectrum and seize leadership in the very high-tech nodes the US had reserved for itself. Initiatives like “Made in China 2025” were explicit declarations of this intent: to use the power of its manufacturing base to dominate the future of AI, 5G, robotics, and biotechnology.

This offensive push collided with a dawning, defensive realization in Washington. The United States discovered that its control over the “brain” was critically vulnerable without a secure “body.” It could design the world’s most advanced semiconductors, but found it could not mass-produce them. It could invent life-saving pharmaceuticals, but found the precursor chemicals were made exclusively in China. The COVID-19 pandemic laid this vulnerability bare for all to see.

The result is the central dynamic of our time: a great mirrored rebalancing, as both powers now scramble to re-integrate the full GVC spectrum to secure their interests. China is pushing upwards, trying to complete its vertical integration by building a self-sufficient innovation layer to match its production might. The United States, in a dramatic reversal of policy, is scrambling to re-integrate downwards. Through massive state interventions like the CHIPS and IRA acts, it is attempting to rebuild the domestic manufacturing “body” it once discarded, recognizing that without it, its innovation “brain” cannot survive in a contested world. The GVC is no longer a collaborative space for efficiency; it is a zero-sum battleground for ecosystem control.

Box 2.1 | Competing Ecosystems – From Fragmented Chains to Vertical Integration

The architecture of a Global Value Chain (GVC) is not a static economic fact; it is a direct reflection of the prevailing geopolitical logic of its time. The post-Cold War era, defined by the perceived security of the U.S.-led order, gave rise to GVCs built on a philosophy of efficiency and allied specialization. In this environment, it was considered safe and optimal to fragment production across a network of trusted partners. The semiconductor industry, with its complex web of interdependencies, is the quintessential product of this logic.

However, the new era of systemic competition has inverted this philosophy. The guiding logic is no longer efficiency, but resilience and strategic dominance. This has given rise to a new model of GVC architecture, one built not on collaborative specialization, but on a “whole-of-nation” effort to achieve full-spectrum, vertical integration. China’s rise in green technology is the prime example of this new model in action. It reflects a deliberate industrial strategy to achieve overwhelming market dominance, a strategy made possible by China’s “exceptional” combination of continental scale and state-directed power, which allows it to attempt a level of integration once thought impossible for a single nation.

A detailed comparison of these two ecosystems reveals not just different industrial structures, but two fundamentally opposing philosophies of national power in the 21st century.

Part 1: The Semiconductor Value Chain – A System of Interdependent Chokepoints

The semiconductor Global Value Chain (GVC) was the quintessential product of globalization, creating a system of profound, asymmetric dependency. An analysis of its key stages reveals a clear geographic division of labor.

- A. Chip Design (The “Brain”): This foundational, high-value stage is dominated by the U.S. and its allies. American firms Synopsys (31%) and Cadence (30%), along with the US/German Siemens EDA (13%), control approximately 74% of the vital Electronic Design Automation (EDA) software market. This gives the U.S. a powerful strategic chokepoint, as virtually every advanced chip in the world is designed using its software.

- B. Manufacturing Equipment (The “Tools”): The complex machinery required for fabrication is controlled by a similar oligopoly. ASML (Netherlands) holds a 100% monopoly on the essential EUV lithography machines, while American firms like Applied Materials and Lam Research, and Japan’s Tokyo Electron, dominate other critical segments. Tellingly, while production is concentrated in the West, China is the largest single buyer, accounting for over 42% of all equipment purchases in 2024 as it races to build domestic capacity.

- C. Advanced Manufacturing (The “Heart”): The physical production of the world’s most advanced chips (<10nm) is almost entirely concentrated in Asia. In the first quarter of 2025, Taiwan’s TSMC held a dominant 67.6% of the global foundry market, with South Korea’s Samsung a distant second at 7.7%. This creates a critical dependency for the U.S. and the West, which rely on this region for their most vital components.

- D. Assembly, Test, & Packaging (ATP) (The “Body”): The final, labor-intensive stage is also centered in Asia. In 2022, Mainland China held the largest share of global ATP capacity at 30%, followed by Taiwan with 27%. Southeast Asia (notably Malaysia and the Philippines) collectively held nearly 20%. This geographic concentration makes the back-end of the supply chain highly vulnerable to regional disruptions.

This fragmented ecosystem, once a model of efficiency, is now seen as a source of extreme strategic vulnerability, fueling a global race by both the U.S. (via the CHIPS Act) and China (via its “Big Fund”) to onshore and control the entire value chain.

Table 1: Semiconductor Supply Chain – A System of Interdependent Chokepoints (2024-2025 Data)

| Value Chain Segment | Key Metric | Leading Players & Market Share (%) |

| Overall Market | Global Sales (2024) | $627.6 Billion (+19.1% YoY) |

| Chip Design (EDA/IP) | Global EDA Software Market Share (2024) | USA-led oligopoly (Synopsys, Cadence, Siemens EDA): ~74% |

| Manufacturing Equipment | Share of Global Equipment Purchases (2024) | China: 42.3% |

| Advanced Manufacturing (<10nm) | Global Foundry Market Share (Q1 2025) | Taiwan (TSMC): 67.6% South Korea (Samsung): 7.7% |

| Assembly, Test, & Packaging (ATP) | Geographic Capacity Share (2022) | China: 30% Taiwan: 27% |

Part 2: The Solar PV Value Chain – A Model of State-Led Vertical Integration

In stark contrast, China has demonstrated a new model of GVC control in solar PV, achieving overwhelming dominance across every key stage of the value chain through a concerted, state-led industrial strategy.

- A. Polysilicon (Upstream Raw Material): China was set to produce 89% of the world’s solar-grade polysilicon in 2024, the foundational material for the industry. Its capacity share in this and other upstream components is projected to reach almost 95%.

- B. Wafers & Cells (Midstream Components): Chinese control here is nearly absolute. In 2024, China’s wafer production reached 753 GW—an output far exceeding the entire world’s annual installation demand of ~600 GW. This massive overcapacity allows it to dictate global prices.

- C. Modules (Downstream Finished Product): The global market for finished solar panels is dominated by Chinese brands. In 2023, the top four Chinese firms—JinkoSolar, JA Solar, LONGi, and Trina Solar—controlled a combined 68.5% of the global market.

Table 2: Solar PV Supply Chain – A Model of Vertical Integration (2024-2025 Data)

| Value Chain Segment | Key Metric | Leading Player & Market Share (%) |

| Overall Market | Global Installations (2024) | ~600 GW (China accounted for nearly 60% of this total) |

| Polysilicon (Upstream) | Global Production Share (2024) | China: 89% |

| Wafers & Cells (Midstream) | Global Manufacturing Capacity Share | China: Approaching 95% |

| Modules (Downstream) | Global Market Share (2023) | Top 4 Chinese Brands (Jinko, JA, LONGi, Trina): 68.5% |

Conclusion: The semiconductor GVC represents the past—a model of globalized efficiency that created a fragile interdependence and is now fracturing under geopolitical pressure. China’s solar GVC represents the new reality—a model of strategic resilience and dominance achieved through vertical integration, creating a one-way dependency that the U.S. and its allies are now desperately trying to counter in other critical sectors.

Sources:

- Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA), Gartner, The Futurum Group, TrendForce, SEMI, Counterpoint Research, Mordor Intelligence, company financial reports.

- International Energy Agency (IEA), Wood Mackenzie, Precedence Research, InfoLink, GlobalData, company reports.

Chapter 3: The Home Front: The Fault Lines of a Fissured Nation

As the United States pivots to confront a new era of great power competition, can it muster the necessary national cohesion and resources to re-industrialize, or will its strategic ambitions fracture against the deep internal fault lines created by the very decades of hollowing-out it now seeks to reverse?

The contest with China is not merely an external challenge; it is a harsh mirror reflecting America’s own internal divisions and structural weaknesses. The grand ambition to rebuild the nation’s industrial bedrock is colliding with at least four critical domestic fault lines—economic, social, and political—that will ultimately determine its fate. These are not peripheral issues; they are the central battleground where America’s capacity for renewal will be won or lost.

3.1 The Total Cost Challenge and the Dollar’s Burden

The most immediate brake on America’s re-industrialization ambition is the immense, multi-faceted cost structure of its domestic economy. While the wage gap with countries like China was the convenient excuse for decades of offshoring, the reality is far more complex and challenging. The true obstacle is the total cost of production, a formidable matrix of interlocking factors that cannot be solved by simple protectionism or subsidies alone. This includes high direct costs for labor, land, and energy relative to global competitors. It also includes the immense expense and difficulty of navigating a complex and often litigious regulatory environment.

Beyond these direct expenses lie deeper, systemic costs born from decades of neglect. Rebuilding a semiconductor fab is one thing; resurrecting the intricate domestic supplier ecosystem of specialized chemical providers, precision tool makers, and equipment maintenance technicians that must support it is another challenge entirely. The atrophied state of these networks means that even new, state-of-the-art factories may remain dependent on foreign inputs, negating the goal of resilience and keeping costs high. Compounding this is a critical shortage of skilled industrial labor—from welders and machinists to advanced manufacturing operators—which inflates wages for scarce talent and necessitates costly, long-term training initiatives.

This deep structural cost disadvantage is powerfully reinforced by the unique role of the US dollar in the global financial system. The dollar’s status as the world’s primary reserve currency, often hailed as an “exorbitant privilege,” functions as an “exorbitant burden” on domestic manufacturing. As economists like Michael Pettis have compellingly argued, to supply the world with the dollar liquidity it demands for trade and reserves, the United States must, by accounting identity, run a persistent current account deficit. It must absorb the excess production and savings of the rest of the world, making it the global “consumer of last resort.” This structural reality exerts a constant upward pressure on the dollar’s value, making American exports more expensive and imports cheaper. It creates a powerful, self-perpetuating macroeconomic headwind that works directly against any national strategy aimed at reshoring industry and running a trade surplus. America’s financial dominance is thus structurally at odds with its industrial revival.

3.2 The Productivity Gamble and the Bifurcated Nation

The conventional answer to this daunting cost challenge is a surge in productivity. The hope in Washington is that a new wave of automation and artificial intelligence can revolutionize American manufacturing, creating efficiency gains so monumental that they overcome the cost gap. This, however, is a high-stakes gamble, not a guaranteed outcome. While the US remains a frontier innovation leader, there is no assurance that these technologies will deliver a decisive relative advantage. Competitors like China are pouring immense resources into deploying the exact same technologies, often with the advantage of greater scale and state-directed focus. The US is betting it can innovate its way out of a structural hole, a bet whose outcome is deeply uncertain.

More consequentially, the very pursuit of this productivity model over the past several decades has cleaved the nation in two, creating a major social fault line. The hollowing-out of traditional manufacturing did not just eliminate jobs; it destroyed a pathway to middle-class stability for millions of Americans without a college degree. In its place has emerged a bifurcated “two-track” economy. One track consists of hyper-productive, globally-connected innovation hubs on the coasts, which have prospered by managing the high-end, intangible nodes of the GVCs. The other track is the vast landscape of former industrial heartlands, which have been left with stagnant wages, diminished opportunities, and a profound sense of economic and cultural dislocation. This is not just a gap in income, but a divergence in social trajectory, creating two Americas that increasingly share little in terms of economic experience or future outlook.

3.3 Fiscal Overstretch and the Price of Renewal

The third major fault line is the direct collision between the immense price tag of strategic competition and the nation’s precarious fiscal health. The United States is attempting to fund a generational contest with China from a position of historic fiscal weakness, with its federal debt-to-GDP ratio at levels unseen since the aftermath of World War II. This structural vulnerability places a hard constraint on any strategy for national renewal, creating a dangerous and highly politicized trade-off between investing in future strength and maintaining present fiscal stability.

This tension manifests differently under the two competing models of statecraft:

- The “Planner State” model, exemplified by the previous Biden administration, relies on massive public spending through legislation like the CHIPS Act and the IRA. While justified as essential for national security, this approach placed a new and direct strain on a budget already buckling under the weight of existing entitlement programs and rising interest costs.

- The “Enforcer State” model of the current Trump administration has shifted tactics, aiming to replace direct subsidies with revenue from massive tariffs while simultaneously pursuing large-scale tax cuts. This creates a different but equally perilous fiscal dynamic, where the revenue generated from protectionism is unlikely to offset the costs of reduced tax receipts, potentially leading to even larger structural deficits.

Regardless of the specific policy mix—whether subsidies, tax cuts, or tariffs—the underlying reality is the same. The entire system is dependent on the “exorbitant privilege” of the U.S. dollar, which allows the nation to finance its chronic deficits cheaply. This reliance is itself a profound strategic vulnerability. Any erosion in global confidence in U.S. debt, whether triggered by excessive spending or unsustainable tax cuts, could trigger a fiscal crisis, forcing an impossible choice between funding the strategic competition with China and servicing its own debt.

3.4 Political Polarization and the Collapse of Consensus

Perhaps the most critical fault line is the one that runs through the American political system itself. The socio-economic fractures described above have become the fuel for a deep and bitter political polarization that now threatens to paralyze any attempt at a coherent, long-term grand strategy. The economic grievances and cultural anxieties of the communities left behind by de-industrialization have been powerfully harnessed by populist movements, transforming economic policy into a front line of the culture war.

This has made national strategy subject to a destructive “policy whipsaw.” What one administration builds, the next may seek to dismantle. The IRA’s green energy investments, for example, are lauded by one party as a vital tool for competing with China but are simultaneously attacked by the other as “woke industrial policy.” This extreme volatility makes it nearly impossible to foster the stable, predictable environment that is essential for the multi-decade, public-private partnerships required to rebuild entire industrial ecosystems. Private capital, hesitant to commit billions to projects whose subsidies could vanish after the election, will either sit on the sidelines or demand a higher risk premium. This internal political dysfunction stands in stark contrast to the unified, state-directed, long-term planning of a competitor like China, and it may represent America’s single greatest strategic disadvantage. The nation cannot hope to win a generational competition with the outside world if it is fighting a permanent war with itself.

Box 3.1 | The Dollar’s ‘Exorbitant Burden’

The U.S. dollar’s status as the world’s primary reserve currency is a source of immense American power, often called an “exorbitant privilege.” However, this privilege comes with a structural curse—an “exorbitant burden”—that acts as a powerful, permanent brake on domestic manufacturing. Understanding this paradox is crucial to grasping why a sustainable re-industrialization of the United States is so difficult. The logic unfolds in two stages: the original dilemma under the gold standard, and its modern form today.

1. The Original Warning: The Triffin Dilemma (Bretton Woods Era)

In the 1960s, under the Bretton Woods system where the dollar was pegged to gold, economist Robert Triffin identified a fundamental flaw. For the global economy to grow, it needed more dollars to finance trade and to be held as reserves. For the world to get more dollars, the United States had to run deficits and send more dollars abroad than it took in.

This created a fatal contradiction:

- If the U.S. didn’t run deficits, the world economy would run short of liquidity and stagnate.

- If the U.S. did run deficits, the flood of dollars overseas would eventually exceed its gold reserves, destroying global confidence that the dollar was “as good as gold.”

This dilemma predicted that a system based on a single national currency as the world’s reserve was doomed to instability. This instability led to the collapse of the gold standard in 1971.

2. The Modern “Exorbitant Burden” (The Michael Pettis Argument)

After 1971, the dollar was no longer backed by gold, but its central role remained. In this new era, the paradox takes a different but equally powerful form, as compellingly argued by economists like Michael Pettis. The mechanism is no longer about gold, but about capital flows.

The logic is an inescapable accounting identity:

- Step 1: The World Needs a Safe Haven for Savings. For various reasons (high domestic savings rates, export-led growth models), many countries—most notably China, Germany, and Japan—produce more than they consume, generating massive pools of excess savings. These countries need a safe place to park this capital.

- Step 2: The U.S. is the World’s Safe Haven. The U.S. financial market, with its depth, transparency, and rule of law, is the world’s primary destination for these savings. Foreign central banks and investors take their excess capital and buy U.S. assets, primarily Treasury bonds.

- Step 3: The Inescapable Accounting. For foreign capital to flow into the United States (a capital account surplus), the U.S. must, by definition, run a corresponding current account deficit. There is no other way for the global balance of payments to balance. A current account deficit means the country is buying more goods and services from the world than it sells.

- Step 4: The U.S. as “Consumer of Last Resort.” This accounting identity forces the U.S. into the structural role of absorbing the world’s excess production. It must be a net importer to allow other countries to be net exporters and to provide a home for their capital. This structural need to absorb foreign capital keeps the dollar’s value persistently higher than it would be based on trade fundamentals alone.

Conclusion: The Brake on Manufacturing Competitiveness

This structural role directly undermines domestic manufacturing in two ways:

- An Overvalued Currency: The constant foreign demand for U.S. financial assets keeps the dollar strong, making American exports more expensive on the global market and imports cheaper at home. This acts as a permanent penalty on U.S. producers trying to compete.

- An Incentive to Offshore: For a U.S. corporation, this dynamic creates a powerful incentive to move production to a lower-cost country and then re-import the finished goods back into the U.S., which is structurally positioned as the world’s primary buyer.

In essence, America’s role as the provider of the world’s safe asset forces it into a role as the world’s primary consumer. This financial dominance is therefore fundamentally at odds with any ambition to become a net producer of manufactured goods again. The “exorbitant privilege” of cheap financing is paid for by the “exorbitant burden” placed on its industrial base.

Box 3.2 | The Hollowing-Out of the American Industrial Base: An Unfolding History of Choice and Consequence

The decline of American manufacturing as a source of mass employment was not a single event, but a complex and organic process that unfolded over decades. It was not a simple story of automation versus trade, but an evolution driven by a shifting set of structural pressures, technological opportunities, and deliberate corporate choices. To understand the profound internal fractures now facing the United States, one must deconstruct this history and the two distinct epochs that define it.

1. Act I (c. 1970–2000): The Era of Domestic Productivity and Rising Competition

The story begins in the 1970s, as the U.S. industrial base, for the first time since World War II, faced intense international competition from a rebuilt Europe and Japan. This new pressure created an urgent need for American firms to increase efficiency and cut costs. The first major opportunity to do so came from within: the computer revolution, which unleashed a powerful wave of domestic automation.

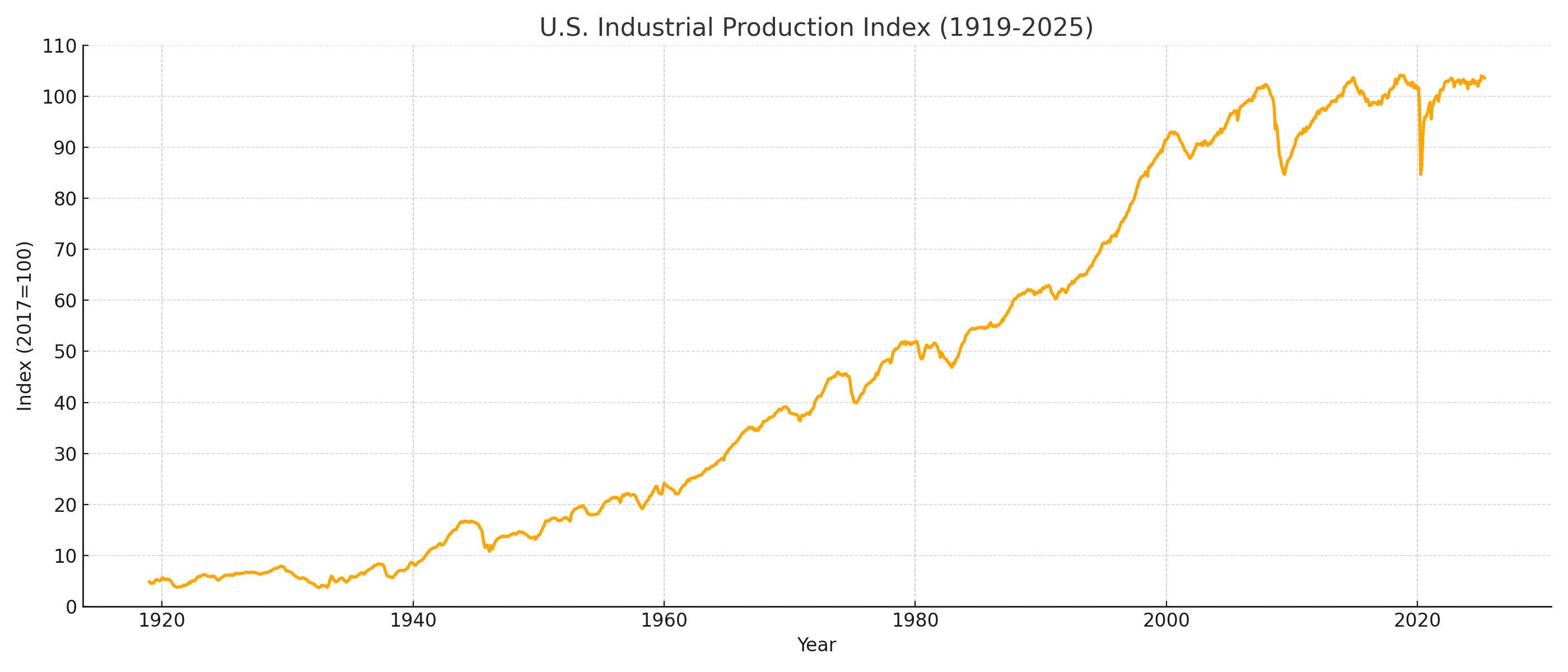

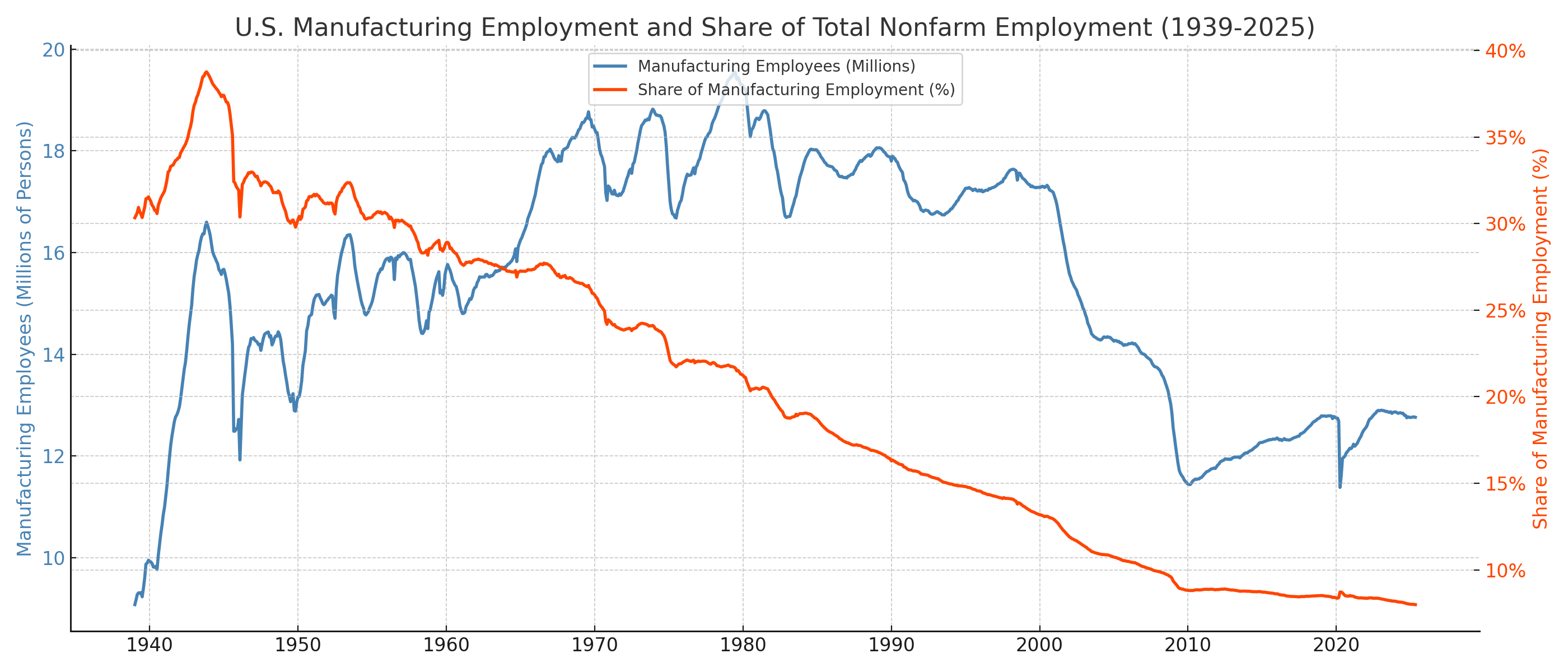

During this period, U.S. factories invested heavily in new technologies, leading to significant productivity gains. The data clearly shows the signature of this trend: real manufacturing output continued to grow robustly, yet the sector’s share of the national workforce began a long, gradual decline. From 1980 to 2000, manufacturing productivity surged at an average of 3.3% per year, while output grew at a slower 2.2%. This mathematical inversion—where efficiency gains outpaced the growth in demand—meant that fewer workers were needed each year to produce more goods. This was a story of a technologically advancing industrial base adapting to new competitive realities.

2. Act II (c. 2000–Present): The “China Shock” and the Great Acceleration of Offshoring

The dynamic shifted violently around the year 2000. China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) presented a new and far more powerful opportunity for cost reduction: global labor arbitrage on an unprecedented scale. This was enabled by the post-1971 global financial system and justified by the ascendant corporate ideology of shareholder value maximization.

The choice for corporate leaders was no longer just about automating at home. The new strategy was to “slice up the value chain”—keeping the high-value “brain” (R&D, design, finance) in the United States while outsourcing the manufacturing “body” abroad. This unleashed the “China Shock,” a wave of import competition that was the definitive cause of a catastrophic collapse in U.S. factory employment. The data signature changed completely:

- Employment plummeted, with 5.8 million manufacturing jobs lost between 2000 and 2010.

- Critically, the long, steady rise in real manufacturing output itself stalled and stagnated for over a decade, signaling that entire productive ecosystems were being moved offshore.

Recent economic research has revealed that much of the measured “productivity growth” during this era was a statistical illusion. This “phantom productivity” was created when the cost savings from offshoring were misattributed in national accounts as gains in domestic efficiency, masking the true weakness of the industrial base and making the official output data from 2000 onward a likely overestimation.

Chart A: U.S. Manufacturing Output (showing robust growth until ~2000, followed by stagnation). Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data.

Chart B: U.S. Manufacturing Employment as a Share of Total Nonfarm Employment (showing the long decline, accelerating after 2000). Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data.

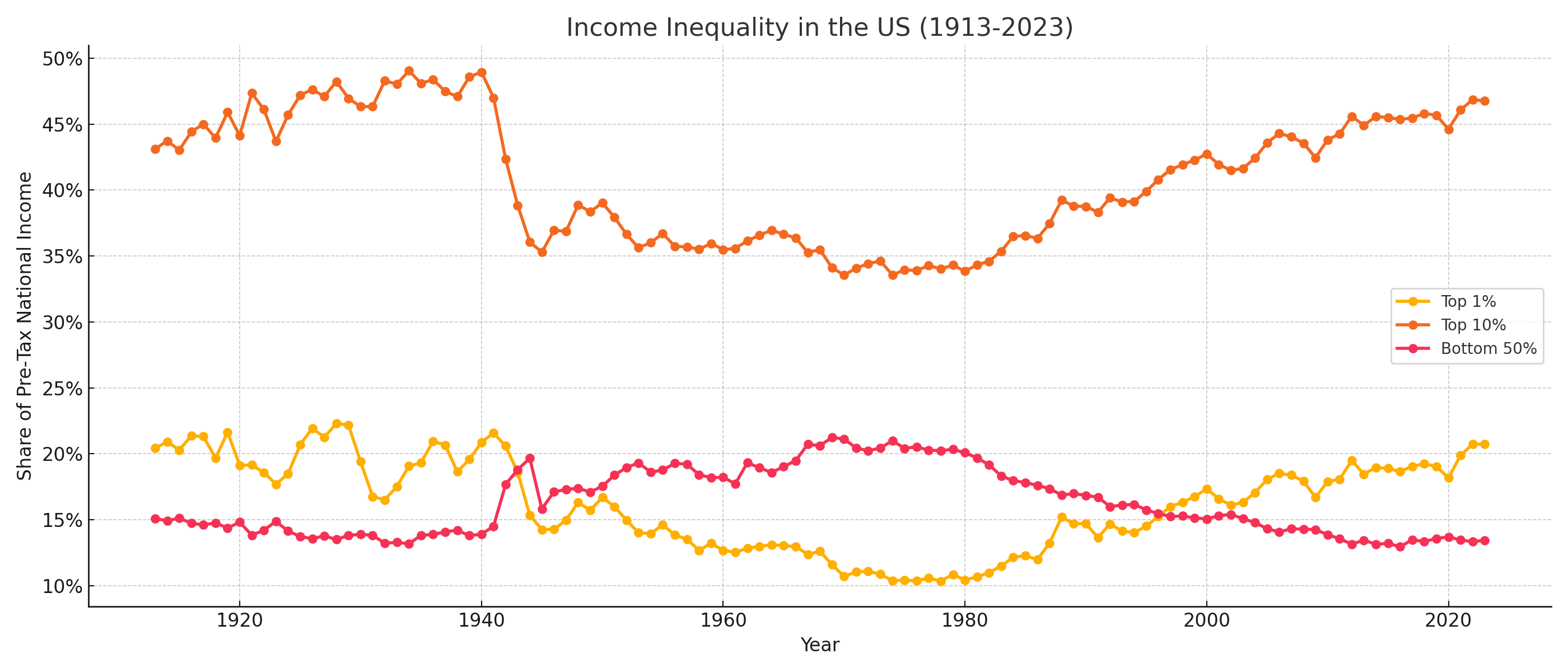

Chart C: The Great Divergence: U.S. National Income Shares (showing the Top 10% share rising as the Bottom 50% share falls, with the divergence accelerating after the 1970s). Source: World Inequality Database.

3. Conclusion: The Legacy of a Broken Social Contract and Strategic Vulnerability

This complex, fifty-year evolution was not an inevitable fatality, but the result of choices made within an evolving set of structural opportunities. The consequence, however, was a profound redistribution of wealth and power. The owners of capital reaped enormous rewards from globalization, while the industrial working class paid the price. The source of the deep social tension and political resentment that defines the United States today is this perception of a broken social contract.

The most insidious long-term cost (from a competitive perspective) was the systemic erosion of industrial “savoir-faire”—the irreplaceable, practical knowledge of technicians and the deep capabilities of entire supplier networks. This creates a critical “time mismatch” at the heart of America’s current strategic dilemma. The U.S. faces an immediate, urgent need to rebuild its industrial power to compete in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, but the human capital and ecosystems required cannot be recreated overnight. This internal fracturing, born from the deliberate choices of a previous era, directly weakens America’s ability to forge the unity and collective will required to stand as a cohesive power on the world stage.

Chapter 4: The External Chessboard: Systemic Drags on American Power

As a fractured and fiscally strained United States attempts to reassert its industrial primacy, how do its strategic ambitions collide with the entrenched realities of a globalized system it no longer fully controls—a system marked by the powerful inertia of rival-centric supply chains, the defiance of increasingly autonomous allies, and the slow-burn blowback from its own use of economic coercion?

While the previous chapter detailed the internal fault lines constraining American renewal, the external landscape presents an equally formidable set of challenges. The US is discovering that redirecting global flows of capital, technology, and trade is akin to altering the course of a massive river; the current is powerful, and the old channels run deep. America’s strategy is being actively shaped and resisted by four primary external drags.

4.1 The Inertia of the China-Centric Ecosystem

The greatest external obstacle to the American project of GVC reconfiguration is the sheer gravitational pull of the China-centric techno-industrial ecosystem. The popular rhetoric of “decoupling” or “de-risking” vastly underestimates the deep, structural integration that has been built over three decades. This is not a simple matter of moving final assembly from one country to another. As established in Chapter 2, China is not just a location for factories; it is a dense, three-dimensional ecosystem where innovation, physical infrastructure, and human capital are interwoven with an efficiency and scale that are, for now, impossible to replicate elsewhere.

The “stickiness” of this ecosystem is multifaceted. First is the unparalleled advantage of scale. Years of state-directed investment and fierce internal competition have created a manufacturing apparatus that can produce goods with a speed and cost-efficiency that smaller, nascent industrial hubs in other countries cannot match. Second, and more importantly, is the completeness of its supplier networks. A multinational corporation may successfully move a final assembly plant to Vietnam or Mexico, only to find that 80% of the critical components—from specialized screws and plastic moldings to advanced electronic modules—must still be sourced from mainland China. This reality often reduces “friend-shoring” to a logistical illusion—a “transshipment” strategy where goods are simply rerouted through third countries to circumvent tariffs, while the core dependency on China’s industrial heartland remains firmly intact.

Furthermore, the ecosystem’s gravity is amplified by China’s dual role as both the world’s factory and one of its largest and most crucial consumer markets. For many of America’s most important allies, particularly industrial exporters like Germany, abandoning the Chinese market to align with a confrontational US strategy is corporate suicide. The revenues generated from selling cars, machinery, and luxury goods in China are what fund their own domestic R&D and employment. This creates a fundamental and often irreconcilable conflict of interest between Washington’s geostrategic objectives and the vital commercial imperatives of its own and allied companies, giving Beijing a powerful lever of influence.

4.2 The Tech Diffusion Dilemma

A second major drag stems from the inherent difficulty of containing technological progress in a globalized world. The US strategy of imposing a “tech blockade”—using export controls to deny China access to critical technologies like advanced semiconductors—is an audacious attempt to halt a rival’s ascent up the value chain. It represents a fundamental belief that America can and should act as the gatekeeper of global innovation, a stance that explicitly subordinates the traditional ideals of open, collaborative development to the harsher logic of national security and power politics. However, this is an inherently leaky and defensive posture with a high risk of backfiring.

While the US and its key allies do control critical chokepoints in the semiconductor ecosystem, technology, by its nature, diffuses. Knowledge, talent, and capital are fluid. The American blockade, while causing significant short-term pain for Chinese firms, has also created the most powerful possible incentive for Beijing to pursue its “whole-of-nation” drive for technological self-sufficiency. By making it a matter of national survival, the U.S. sanctions may ultimately accelerate, rather than prevent, China’s emergence as an indigenous technological power.

Moreover, the effectiveness of the blockade is entirely dependent on the complete and enthusiastic compliance of allies. This is far from guaranteed. For technology leaders like ASML in the Netherlands (which produces essential lithography equipment) or advanced materials suppliers in Japan and South Korea, China represents a massive and lucrative market. Sustained US pressure forces these allied governments into a painful dilemma: sacrifice billions in corporate revenue and risk economic retaliation from Beijing to prove their loyalty to Washington, or discreetly allow trade to continue where possible. Any gap in this coalition, any instance of an allied firm putting its commercial interests first, creates an opening that China can and will exploit to circumvent the controls.

4.3 The Rise of Allied “Strategic Autonomy”

This leads directly to the third systemic drag: the steady drift of key US allies towards “strategic autonomy.” America’s vast network of alliances is its single greatest asymmetric advantage over China. Yet this asset is becoming more conditional and complex. Allies in Europe and Asia increasingly refuse to see the world in binary terms or to function as passive followers in a US-led crusade. This autonomy drift is driven by a convergence of factors. First is the perception of American unreliability, powerfully reinforced by the domestic “policy whipsaw” that sees US strategy pivot with each election cycle. Second are the divergent economic interests just described.

This quest for autonomy manifests in various ways. The European Union’s push for its own industrial champions and regulatory sovereignty is a clear attempt to become a third pole, capable of resisting economic pressures from both Washington and Beijing. French President Emmanuel Macron’s calls for Europe to avoid being a mere “vassal” in a US-China conflict over Taiwan captures this sentiment perfectly. In the Indo-Pacific, nations eagerly join US-led security groupings like the Quad while simultaneously being central members of the China-centric RCEP trade pact. They are engaging in classic hedging behavior. The result is that the US cannot summon a unified, Cold War-style bloc. It must instead navigate a messy “à la carte” world where partners align on some issues (like freedom of navigation) while openly disagreeing or competing on others (like trade and industrial policy).

4.4 The Blowback from a “Weaponized” Dollar

Finally, the US strategy is constrained by the long-term consequences of its own financial power. The increasing use of the dollar and the SWIFT financial messaging system as tools of geopolitical coercion—most dramatically demonstrated by the sweeping sanctions on Russia—is actively incentivizing the rest of the world to build alternatives. While devastatingly effective in the short term, this “weaponization of interdependence” served as a stark wake-up call for every nation, friend and foe alike, of its own vulnerability to American financial statecraft.

This has undeniably accelerated efforts to create a “de-dollarized” world. China is actively promoting its Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) as a potential rival to SWIFT. A growing number of significant bilateral trade deals—between China and Russia, Brazil, and even key Middle Eastern oil producers—are being settled in local currencies. Central banks around the globe are slowly but steadily diversifying their foreign exchange reserves, reducing the share held in US dollars. While the dollar’s dominance is in no immediate danger—underpinned as it is by the unmatched size, depth, and liquidity of US capital markets—the long-term vector is clear. Each time the US uses financial sanctions for coercive ends, it gives every other country a stronger reason to invest in building an exit ramp. In the long run, the US may be trading short-term coercive power for the slow erosion of its long-term systemic influence.

Box 4.1 | The Dollar’s Dilemma: Navigating a Multipolar Financial World

The U.S. dollar’s role as the anchor of the global financial system, once an unambiguous symbol of American power, has become a profound strategic dilemma. While still a source of immense privilege, it now imposes significant burdens that are being challenged by both internal U.S. imperatives and external geopolitical shifts.

1. The Two Eras of Dollar Dominance

The dollar’s function has fundamentally changed over time:

- The “Golden Age” (c. 1945-1971): In this period, the dollar’s role was symbiotic with U.S. industrial might. A world in need of American capital goods used the dollars it received through U.S. aid and investment to buy those very products. The system reinforced American manufacturing.

- The “Exorbitant Burden” Era (Post-1971): In a world of globalized capital and new industrial competitors, the dollar’s role became antagonistic to U.S. industrial might. The structural global demand for dollars as a safe asset keeps the currency strong, making U.S. goods uncompetitive and forcing the U.S. to be the “consumer of last resort.”

2. America’s Unresolved Trilemma: The Three Strategic Options

The U.S. now faces a trilemma between three competing goals: (1) maintaining financial hegemony, (2) rebuilding industrial competitiveness, and (3) preserving its alliance network. The oscillation between administrations reflects a deep national uncertainty about which path to prioritize. As we have discussed, these paths are:

- Option 1: Unilateral Power (Tariff-led): Prioritizes U.S. industrial revival by using raw power to force reshoring, at the expense of allies and the existing trade order.

- Option 2: Alliance-Based Constrainment (Subsidy/Tech-led): Prioritizes the alliance network to collectively manage China’s rise, at the expense of pure economic efficiency and creating internal friction.

- Option 3: Systemic Reform: This theoretical path would sacrifice U.S. financial hegemony (the “exorbitant privilege”) to save its industrial base. It remains a non-starter in Washington as it would require voluntarily relinquishing a core pillar of American power.

3. The World’s Ambivalence: Beneficiary and Hostage of the Dollar

Other countries have a deeply conflicted relationship with the dollar system, explaining why reform is so difficult.

- The “Push” for De-Dollarization: Rival powers like China and Russia, along with other nations, seek to reduce their vulnerability to U.S. sanctions and monetary policy. This drives initiatives like the expansion of BRICS, the promotion of bilateral trade in local currencies, and the development of alternative payment systems like CIPS.

- The “Pull” of the System (The Bonanza): At the same time, export-led surplus countries, especially China, are major beneficiaries of the current system. They rely on the U.S. consumer to absorb their excess production and on the deep, liquid U.S. financial markets to safely invest their massive savings. A sudden collapse of this system would be catastrophic for their own economic models.

4. U.S. Dollar Share of Global Foreign Exchange Reserves: 1944-2025

| Year | U.S. Dollar Share (%) | Key Events & Context |

| 1944 | ~20% | Bretton Woods Agreement signed. U.S. emerges as the dominant industrial power, but the British pound sterling is still a major global reserve currency. |

| 1950 | ~32% | The dollar’s role grows rapidly with the Marshall Plan and U.S. industrial exports, but sterling still holds a majority of reserves. |

| 1960 | ~61% | The dollar has clearly surpassed sterling; U.S. economic dominance is at its peak. |

| 1970 | ~85% | Dollar’s share peaks under the Bretton Woods system. |

| 1975 | ~85% | Post-Nixon Shock; system moves to floating rates, but the dollar remains central due to a lack of alternatives. |

| 1980 | ~58% | High U.S. inflation and oil crises weaken confidence. |

| 1985 | ~57% | Plaza Accord leads to coordinated action to devalue the dollar against the Yen and Deutsche Mark. |

| 1990 | ~47% | Rise of the Japanese Yen and German Deutsche Mark as credible alternatives. |

| 1995 | ~59% | Post-Cold War “unipolar moment” begins; U.S. economic resurgence boosts confidence. |

| 2001 | ~71% | Post-Soviet collapse & Dot-com boom; peak of modern dollar dominance. |

| 2005 | 66.5% | The Euro emerges as a major alternative, beginning the dollar’s slow diversification. |

| 2010 | 62.1% | Post-Global Financial Crisis; questions about U.S. financial stability accelerate diversification. |

| 2015 | 65.7% | Temporary rebound due to the Eurozone debt crisis and relative U.S. strength. |

| 2020 | 59.0% | Renewed diversification trend accelerates with the rise of China and geopolitical competition. |

| 2023 | 58.4% | Sanctions on Russia further encourage some nations to seek non-dollar alternatives. |

| 2025 | ~58% | Slow, structural erosion continues amid a contested global order, but the dollar remains dominant. |

Commentary on the Data

This historical series reveals four distinct eras in the dollar’s life as a global reserve currency:

- The Ascent (1950s-1970s): Following World War II, the dollar rapidly replaced the British pound sterling as the world’s primary reserve asset. Backed by America’s overwhelming industrial supremacy, its share of global reserves climbed steadily, solidifying its role as the anchor of the Bretton Woods system.

- The Period of Turmoil (1970s-1990s): The end of the gold standard in 1971, coupled with high U.S. inflation and the rise of Japan and Germany as industrial competitors, led to a significant loss of confidence. The dollar’s share fell sharply as central banks diversified into the Deutsche Mark and the Yen.

- The Unipolar Peak (1990s-early 2000s): The collapse of the Soviet Union and the U.S. tech boom of the 1990s ushered in an era of unrivaled American dominance. With no credible geopolitical or economic challenger, confidence in the dollar surged, and its share of global reserves reached its modern peak of over 70%.

- The Slow, Structural Decline (c. 2002-Present): For the past two decades, the dollar’s share has been in a slow but unmistakable decline. This erosion has been driven by several factors: the introduction of the Euro as a major alternative, the 2008 financial crisis which originated in the U.S., and most recently, the intensifying geopolitical competition with China and Russia, which has accelerated efforts by some nations to “de-dollarize” and reduce their vulnerability to U.S. financial sanctions.

Sources:

- Post-1995 Data: International Monetary Fund, Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER) database.

- Pre-1995 Data: International Monetary Fund, Barry Eichengreen (2014).

Conclusion:

The dollar-centric system persists not because it is optimal, but because it is locked in by a complex, unstable, and deeply entrenched bargain of mutual self-interest. From a realist perspective, the United States is unwilling to voluntarily relinquish the “exorbitant privilege” of cheap financing and its most potent geopolitical weapon. Simultaneously, major surplus countries and economic competitors like China are too dependent on the U.S. market as a “consumer of last resort” and on its deep capital markets as a “bonanza” for their savings to risk a full-blown rupture.

This dynamic is reinforced by a profound, unspoken paradox: the very nations capable of offering an alternative to the dollar have a strong strategic incentive not to do so. As the historical experiences of Japan and Germany show, the rise of a national currency to global reserve status inevitably leads to its appreciation, acting as a powerful brake on the export-led industrial competitiveness that is the foundation of their economic models. China, in particular, is caught in this dilemma. It seeks to reduce its vulnerability to U.S. financial power, but it is unwilling to accept the “exorbitant burden”—a strong Yuan and the potential hollowing-out of its manufacturing base—that would come with replacing the dollar.

Therefore, the external push for “de-dollarization” is not an attempt to crown a new king, but a more limited effort to build a multipolar financial world that dilutes America’s power. This, combined with the profound internal pressure on the U.S. to rebalance its own economy, creates an environment of perpetual friction. The most likely future is not a dramatic replacement of the dollar, but a continued, messy, and slow fragmentation of the global financial order, driven by the contradictory interests of all its major participants.

Chapter 5: The Industrial Policy Lever: A Tale of Two Statecrafts

As the United States unsheathes the powerful but unfamiliar weapon of state-directed industrial policy, can this lever be wielded with the strategic patience and consistency required for a generational competition, or will the nation’s own volatile and deeply polarized political system render its most potent new tool unreliable and ultimately ineffective?

The return of great power politics has forged a new consensus in Washington: the laissez-faire orthodoxy of the past has failed, and the state must now play an active, strategic role in the economy to secure American primacy. However, this unity on the necessity of state intervention masks a profound and deeply divisive schism over its modality. The U.S. has not adopted one industrial policy, but two fundamentally opposed models of state-led capitalism—a “Planner State” and an “Enforcer State”—and the violent oscillation between them is now a central feature of the American strategic landscape.

5.1 The Return of a Forgotten Weapon

The strategic theory behind the recent American turn to industrial policy is a direct rejection of the neoliberal consensus that dominated for forty years. It is a tacit admission that in a geoeconomic struggle against a state-capitalist rival like China, which heavily subsidizes its own industries, the U.S. private sector cannot compete on its own. The immense, long-term risks associated with rebuilding entire techno-industrial ecosystems, especially when faced with the “total cost” disadvantages discussed previously, are too great for corporations to bear alone. This has led to the reclaiming of a forgotten tradition of Hamiltonian economics, where the state actively intervenes to shape economic outcomes in the national interest.

The first model to emerge from this new consensus, exemplified by the legislative achievements of the Biden administration, casts the state as a strategic partner and catalyst. This approach is institutional, collaborative, and long-term. Its architecture is built on landmark legislation like the CHIPS and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which use a suite of constructive incentives—massive tax credits, grants, and public-private consortia—to “de-risk” foundational private investments. This “government-enabled, private sector-led” strategy is a complex, coordinative effort. It is a “Planner State” model that seeks to cultivate a desired outcome by preparing the soil with infrastructure investment, providing the nutrients with targeted subsidies, and creating a stable climate with predictable, long-term policy frameworks. The explicit goal is to coax private capital off the sidelines and back into the difficult, multi-decade project of building resilient domestic supply chains.

The success of such a strategy, however, is entirely dependent on one critical, non-economic factor: time. Rebuilding complex industrial ecosystems, training a skilled workforce, and fostering deep supplier networks is not a short-term project. It requires a decade or more of stable and consistent policy support for investors to have the confidence to make multi-billion-dollar capital commitments. The core requirement for this model of industrial policy is, therefore, strategic patience—a quality that is in desperately short supply within the contemporary American political system. The fundamental problem is a profound mismatch between the long-term timescale of industrial renewal and the short-term, antagonistic cycles of American politics.

5.2 The “Policy Whipsaw”: A Clash of Competing Statecrafts

This mismatch manifests as a debilitating “policy whipsaw.” The bipartisan consensus on the need to compete with China shatters when it comes to the methods. This is not merely a debate over the size of a subsidy or the rate of a tariff; it is a fundamental clash between two different philosophies of state power.

The second model, which defines the “America First” paradigm and has been forcefully reimplemented by the second Trump administration, positions the state as a transactional enforcer. This approach is personal, coercive, and short-term. It is animated by a profound skepticism of the “Planner State,” which it views as a source of bureaucratic inefficiency, wasteful spending, and ideological projects (such as the “woke industrial policy” of the IRA) that burden the private sector.

This “Enforcer State” model rejects the coordinative role in favor of a more direct and confrontational use of state power. It wields a different set of tools: the “stick” of massive, unilateral tariffs to punish foreign competitors and create a brutal incentive to reshore, and the “carrot” of aggressive domestic deregulation and tax cuts to “unleash” capital. Its logic is not to plan an industrial ecosystem, but to use the raw power of the executive to radically alter the incentive structure for private businesses. It is a strategy of shock and bargain, where the state acts as a bouncer at the door of the U.S. economy, using its power to dictate terms.

The “policy whipsaw,” therefore, is the violent oscillation between these two models. The shift from a collaborative, subsidy-led strategy to a unilateral, tariff-led one creates a level of uncertainty that is toxic to long-term investment and strategic planning. This strategic inconsistency, a direct result of America’s internal political divisions, risks becoming its single greatest competitive disadvantage.

5.3 An Asymmetric Disadvantage in a Generational Contest

This internal volatility creates a stark, asymmetric disadvantage for the United States in its competition with China. As detailed in our previous analysis of China’s system, Beijing’s state-capitalist model is built for long-term, consistent strategic execution. Through instruments like its Five-Year Plans and top-level design committees, the Chinese Communist Party can identify strategic industries, allocate massive resources, and sustain that support for decades, subordinating short-term market fluctuations and political disagreements to the overarching national goal. China’s leadership can credibly plan for 2035 and 2049; the American political system, fractured by this deep philosophical divide over the role of the state, struggles to plan past the next election.

Ultimately, the central question of America’s industrial renewal is not whether the policy lever is powerful enough, but whether the political system is coherent enough to wield it effectively over time. The U.S. is attempting to run a strategic marathon with a political apparatus built for two-year sprints, each with the risk of reversing the course of the last. Without a durable, bipartisan national compact on the core tenets of industrial strategy, America’s powerful new weapon risks becoming unreliable in its own hands, leaving the nation’s strategic ambitions hostage to its own internal fractures.

Box 5.1 | The American Re-industrialization Gambit – Can Innovation Outrun Reality?

The United States has embarked on a strategic gambit of historic proportions: a multi-trillion-dollar effort to re-industrialize its economy, secure its supply chains, and reclaim its manufacturing prowess. This endeavor, however, hinges on a central, high-stakes wager: can American leadership in technology, particularly Artificial Intelligence, unleash productivity gains so monumental that they overcome the nation’s profound structural disadvantages? A deep analysis of the data reveals that while a full return to the mass-employment manufacturing of the past is unfeasible, a targeted revival is possible, though its success is far from guaranteed and is constrained by three critical realities: the total cost of production, the paradoxes of productivity, and a severe human capital crisis.

1. The Total Cost Hurdle – Deconstructing the Competitiveness Challenge

A rigorous analysis of U.S. re-industrialization must begin with a clear-eyed assessment of the immense cost hurdle it faces. For decades, corporate offshoring decisions were driven by a narrow focus on direct costs, particularly labor. However, a modern, strategic understanding requires a “Total Cost of Ownership” (TCO) framework, which encompasses a much broader set of variables, from logistics and tariffs to inventory and risk. This comprehensive accounting also includes critical domestic factors such as land access, local and federal taxes, and the significant costs associated with navigating a complex regulatory environment. When analyzed through this comprehensive lens, the challenge for the U.S. becomes clearer, and the strategic importance of a regional, North American approach becomes paramount.

A. The Direct Cost Differential: A Three-Country Comparison

An initial comparison of the primary variable costs—labor and energy—reveals a stark reality.

- Labor Costs: This remains the most significant and persistent cost disadvantage for U.S. domestic manufacturing. As of 2024-2025, the “all-in” hourly manufacturing labor cost in the U.S. is approximately $45, a figure that is nearly ten times that of Mexico (around $4.90) and seven times that of China (around $6.50). This prohibitive gap makes the U.S. uncompetitive for most labor-intensive production.

- Energy Costs: Here, the U.S. holds a significant and growing competitive advantage. The shale gas revolution has provided a powerful advantage in natural gas, with domestic prices being roughly half those in Mexico and China. Furthermore, recent IEA data shows that from 2019-2024, U.S. industrial electricity prices have become highly competitive, more favorable than those in China and significantly lower than in the EU.

This direct cost data highlights a critical strategic reality: a purely national “Re-shore to the U.S.” strategy is often economically unviable for many products. Instead, the data points to the logic of a North American Bloc strategy. While U.S. labor is expensive, its clear advantage in total energy costs and its advanced industrial base make it ideal for capital-intensive processes. Mexico’s significant labor cost advantage makes it ideal for assembly. This creates a powerful symbiotic relationship, a fact underscored by the very structure of regional trade. Therefore, up to 40% of the value of Mexican exports to the U.S. originates from the U.S. itself, in the form of parts and components that are shipped to Mexico for assembly and then re-imported. This stands in stark contrast to imports from China, which contain only about 4% U.S. content due to China’s highly integrated domestic ecosystem. This means that every dollar of manufacturing that shifts from China to Mexico generates a tenfold increase in demand for U.S.-based suppliers.

B. Beyond the Factory Gate: The Strategic Calculus of TCO

A TCO framework reveals numerous “hidden costs” that erode the perceived advantages of distant offshoring and bolster the case for a resilient, regional manufacturing footprint.

- Logistics, Inventory, and Working Capital: Proximity to market is a massive economic lever. The short, 2-3 day transit time from Mexico enables lean, “just-in-time” inventory models, freeing up the immense working capital that would otherwise be frozen for weeks in inventory on a trans-Pacific supply chain. This increases capital efficiency and business agility.

- Tariffs and Geopolitical Risk: The USMCA provides duty-free market access for Mexican goods, a major advantage over Chinese imports, which have been subjected to significant tariffs. This geopolitical risk has become a primary driver for companies reconsidering their supply chain footprint.

- Quality, IP, and Innovation: Geographic proximity allows for tighter quality control, reducing the cost of defects and rework. Operating within the robust U.S. legal framework offers stronger intellectual property protection. Critically, co-locating manufacturing with engineering and design teams fosters the close collaboration essential for process and product innovation.

The TCO model is not merely a better accounting tool; it is a strategic necessity in the new era. A significant majority of companies still rely on outdated costing methods like landed cost, which can lead to a substantial underestimation of the true total cost of offshoring—often by as much as 20 to 30 percent. By quantifying the costs of risk and volatility, the TCO framework reveals that for many products, a regional North American supply chain is not only more resilient but also more cost-competitive than a trans-Pacific one.

2. The Productivity Bet: A Quantitative Feasibility Analysis

The core economic case for U.S. re-industrialization rests on a critical and ambitious wager: that a new wave of technological innovation, centered on Artificial Intelligence (AI) and advanced automation, can deliver a surge in productivity sufficient to make domestic manufacturing cost-competitive. This “Productivity Bet” is the central hypothesis of the entire endeavor. This analysis will deconstruct that bet by creating a simplified model to answer a crucial question: Just how fast does U.S. productivity need to grow to overcome its immense structural cost disadvantages?

A. The Analytical Framework: Why TFP and Why Mexico?

To model this challenge, we must be precise in our methodology.

- The Metric is TFP: The correct metric for this analysis is Total Factor Productivity (TFP), not the simpler labor productivity. TFP measures the “pure” innovation and efficiency gains of an entire system after accounting for all inputs of labor and capital. Since the U.S. strategy is a bet on becoming fundamentally “smarter,” not just on using more machines, TFP is the only metric that can truly measure the success of this innovation-led gambit.

- The Comparator is Mexico: While the overarching geopolitical competition is with China, the immediate economic and operational choice for a company de-risking from Asia to serve the U.S. market is between reshoring (to the U.S.) and near-shoring (to Mexico). Therefore, Mexico serves as the most realistic economic benchmark for this feasibility analysis, framing the challenge within the context of creating a competitive North American industrial bloc.

B. The “Break-Even” Model: Assumptions and Calculation

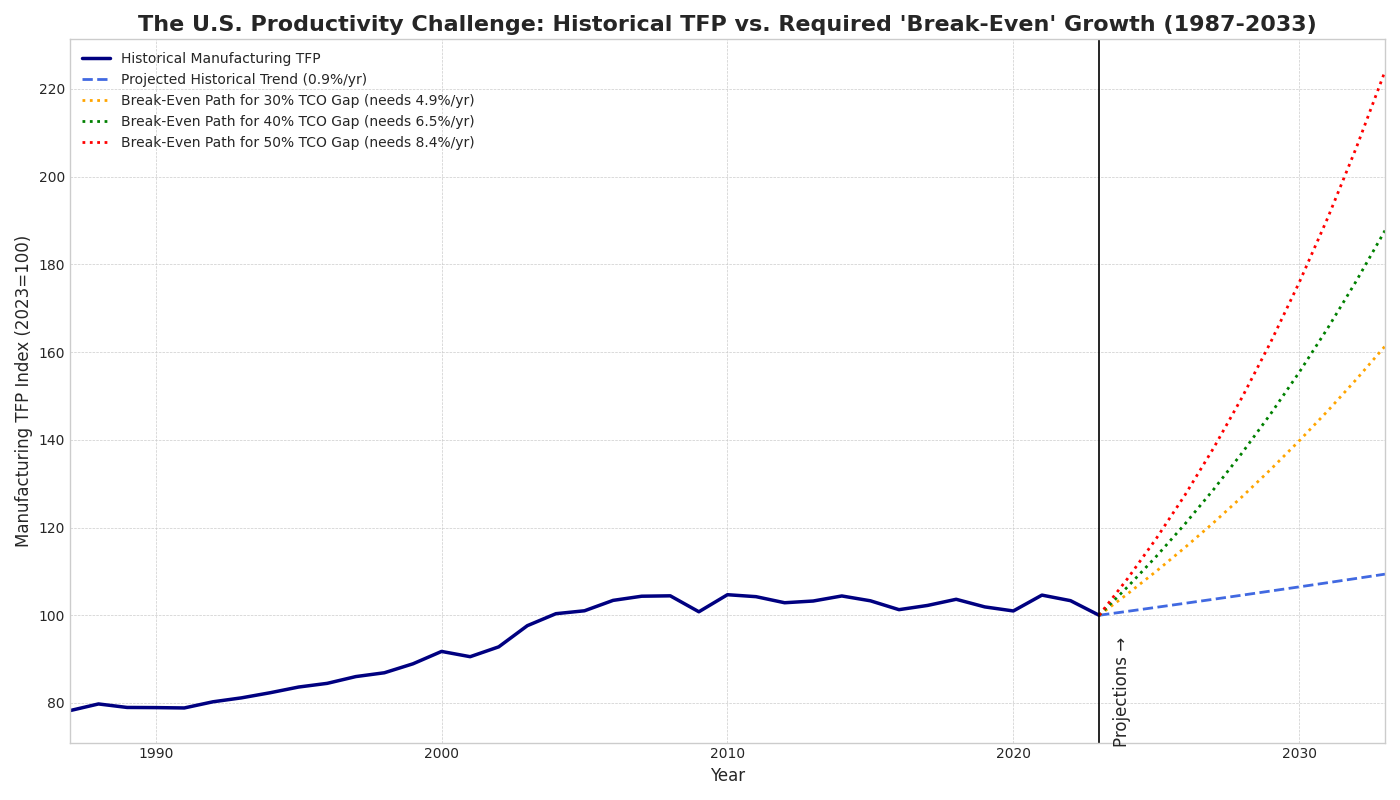

Our model calculates the sustained annual TFP growth rate the U.S. must achieve over a 10-year period (2024-2033) to close its Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) gap with Mexico.

- Assumptions: