Foreword

In the first installment of this series, “Power Politics Reborn: Realism as the Guiding Lens in a Tech-Driven Multipolar Era,” I laid out a broad framework illustrating how great-power competition, viewed through a realist lens, underpins today’s global realignments. Once a systemic shift in power disrupts the status quo, states adapt through measures such as decoupling, reshoring, and industrial planning. At the heart of that adaptation is each nation’s ability to transform innovation into profitable industries—an outcome grounded in robust techno-industrial ecosystems that reinforce geoeconomic clout. Far from introducing any new theory, I simply apply classic realism to emphasize how economic strength—built on tangible technologies and flourishing value chains—remains a decisive pillar of global influence.

Now, with this second article—“Back to Center Stage: China’s Resurgence under Realpolitik with Chinese Characteristics”—I shift attention to the actor perhaps most responsible for unsettling the U.S.-led unipolar order: China.

Why highlight China before turning to the United States? Because China’s rapid economic expansion, technological ambitions, and outward-focused strategies have presented the most formidable challenge to U.S. primacy. As China strives to reduce vulnerabilities in key value chains and elevate its industries across global supply networks, it has provoked strong American responses—ranging from tariffs and export controls to the buzzword of “derisking.” These moves by both Beijing and Washington reflect the reality that economic integration, once a cornerstone of globalization, now increasingly serves as a battlefield in great-power competition. In grappling with social and strategic fallout from deindustrialization, the United States is prioritizing industrial revitalization to remain competitive. China’s resurgence has therefore triggered a cycle of recalibration, prompting not just the U.S. but also other major players (including the EU) to negotiate new rules and power dynamics.

In this article, I examine China’s worldview—shaped by a sense of “national rejuvenation” following the so-called “Century of Humiliation,” and sustained by the conviction that economic might, technological mastery, and supply chain autonomy form the bedrock of national power. A realist perspective highlights how Beijing’s confidence in reshaping the global order coexists with pragmatic caution, mindful that a premature confrontation with the U.S. could jeopardize core objectives. At the same time, as Chinese industries climb the global value chain—particularly in AI, green tech, and advanced manufacturing—China’s competitors keep refining their own strategies, with real ramifications for trade flows, alliances, and industrial ecosystems.

Clarifying the Scope and Next Steps

This series aims to show how realism and power politics intersect with evolving technological and geoeconomic landscapes. Still, it does not claim to comprehensively address every nuance of China’s vast reality. My goal here is to identify pivotal drivers, offer informed interpretations, and explain why China’s ascent so profoundly influences ongoing geopolitical shifts.

I plan a follow-up article that will delve deeper into China’s dual circulation and the broader modernization puzzle—how Beijing aims to harmonize supply and demand, tap its vast domestic market, and further anchor itself at the core of global value chains. Because this present piece outlines China’s strategic direction from the founding of the PRC onward, it only briefly touches on the contradictions inherent in these next development phases. Internal social pressures, changing consumer patterns, and evolving partnerships all factor into the next stage. Recognizing China’s transformation as multifaceted—shaped by local interests, regional diversity, and leadership goals still in flux—this upcoming installment will examine the tension between China’s pursuit of world leadership and its need to reconfigure both internal and external growth models.

Linking Back to the Series

“Back to Center Stage” aligns seamlessly with the overarching themes introduced earlier. China’s rise has reshaped major-power interactions, driving states to reexamine value chains and rework security frameworks. Subsequent articles will focus on the United States and the European Union, each confronting its own historical path, strategic culture, and future ambitions. Through these region-specific lenses, I aim to illustrate how realism, in practice, spurs states to evaluate costs and benefits in a rapidly shifting environment of technological breakthroughs and geoeconomic rivalries.

Ultimately, these analyses are designed to spark reflection rather than prescribe sweeping policy. While each region’s outlook is informed by distinct cultures and constraints, the world remains inherently interdependent—decisions in one corner reverberate globally. By stressing these intricate interconnections, I hope to shed light on how states protect their near-term interests yet also shape collective stability and opportunity. I invite you to read on with an open mind about the multipolar transitions unfolding around us—and the pivotal role China plays in that evolving picture.

Introduction

China’s rise on the world stage is not an accident of economics but a deliberate, strategic project decades in the making. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership, steeped in lessons from history and guided by a realpolitik lens, has pursued national rejuvenation with patient determination. In Beijing’s view, power – economic, technological, and military – is the ultimate guarantor of sovereignty and security in a competitive international system. This analysis offers a deep dive into China’s grand strategy with a focus on its technological and industrial ascent. It examines how historical experience and cultural traditions shape the long-term vision of China’s leaders, how coordinated development policies advance the country’s comprehensive power, and how specific sectors like green technology, artificial intelligence (AI), and semiconductors are wielded as instruments of national strategy. Crucially, this review evaluates China’s choices through Beijing’s own strategic lens, treating its moves not as reactive responses to the West, but as proactive calculations aimed at restoring what China considers as its rightful place in a multipolar world. The throughline is a hard-edged realism: from Mao Zedong to Xi Jinping, Chinese leaders have shared core goals – strengthening the state, pursuing strategic autonomy and self-reliance, and amassing leverage – even as tactics evolved. Understanding China’s mindset on its own terms is vital to grasp the technological and geopolitical competition unfolding in the 21st century.

Historical and Cultural Foundations of Chinese Strategy

China’s strategic behavior today cannot be understood without reference to the weight of history and the depth of its civilizational philosophies. The Chinese worldview is informed by millennia of statecraft – a blend of Confucian ideals, Legalist power politics, and the bitter legacy of a “Century of Humiliation.” These factors shape the values and assumptions of China’s current leadership, molding a strategic culture that prizes patience, national unity, and the ruthless pursuit of strength.

Philosophical Legacies: Confucianism, Legalism, and Realpolitik

Two ancient philosophical currents – Confucianism and Legalism – have long guided Chinese governance and still echo in the CCP’s approach to power. Confucianism emphasizes social harmony, hierarchical order, and moral leadership. It envisions rulers as virtuous guardians of the people, legitimized by benevolence and cultural excellence. Legalism, by contrast, asserts that stability comes only from strong laws and state authority, rooted in a cynical view of human nature. Legalist thinkers like Han Fei Zi advised rulers to enforce strict discipline and wield power unsentimentally to secure the state.

Under President Xi Jinping, the CCP has consciously drawn on both traditions to buttress its rule. As one scholarly analysis notes, Xi’s regime explicitly invokes Confucian and Legalist ideas to legitimize highly centralized one-party control. Confucian rhetoric of “rule by virtue” is used to project an image of paternalistic responsibility, while Legalist themes of law and order justify harsh measures against any threats to stability. By tapping into these deep cultural veins, the Party claims a distinct “Chinese” model of governance, reinforcing “cultural self-confidence” in contrast to Western liberal ideals. In practice, this means that moralistic slogans and crackdowns on dissent go hand in hand. Xi frequently cites Confucius in speeches to stress unity and loyalty, even as his administration implements Legalist-style campaigns against corruption and dissent to tighten the Party’s grip. The fusion of these philosophies provides a time-tested playbook: ensure absolute authority at the top, maintain order through any means necessary, and present it as upholding societal harmony.

Notably, Chinese strategic thought has never shied from realpolitik. Even in dynastic times, emperors employed Confucian benevolence externally and Legalist statecraft internally – a duality often summarized as “Confucian on the outside, Legalist on the inside” (外儒内法). Contemporary China mirrors this. Outwardly, its leaders speak of peace and cooperation, but inwardly they calculate power balances with cold precision. Scholar Alastair Johnston’s research into Chinese strategic culture finds a consistent “parabellum” mindset – a propensity to prepare for and deter conflict – underlying the veneer of Confucian rhetoric. In short, the CCP’s heritage equips it with a deep toolkit of statecraft: ideological flexibility (pragmatism over purity), reverence for centralized authority, and a realist conviction that order comes from strength. These traits, rooted in Confucian and Legalist thought, continue to underwrite China’s grand strategy today.

The Century of Humiliation and National Rejuvenation

Layered atop ancient philosophy is the searing memory of China’s “Century of Humiliation” – roughly the period from the First Opium War in 1839 to the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949. During those hundred years, foreign imperial powers defeated China in war, forced unequal treaties, colonized parts of its territory, and reduced the once-mighty Qing empire to a fractured, semi-colonial state. This era of national trauma left an indelible mark on China’s collective psyche and on the CCP’s foundational narrative. It instilled a determination that such weakness and subjugation must never recur.

From Mao to Xi, Chinese leaders have portrayed the CCP as the historic agent that ended humiliation and began China’s revival. In a 2023 speech, Xi Jinping noted that since its founding, the Party “closely united and led the Chinese people… in working hard for a century to put an end to China’s national humiliation”. Under CCP leadership, he proclaimed, China transformed “from standing up and growing prosperous to becoming strong,” making the nation’s rejuvenation “historically inevitable.”. This narrative of redemption and resurgence is more than propaganda; it genuinely guides policy. The lesson learned is that only comprehensive national power can safeguard sovereignty. The humiliation discourse thus translates into a resolute emphasis on sovereignty, territorial integrity, and state dignity in Chinese strategy. In practical terms, it underpins Beijing’s hard line on issues like Taiwan, Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and the South China Sea – all seen as arenas where any concession could invite a return of foreign domination. “Never again” is the unspoken mantra.

The quest for “national rejuvenation” (民族复兴), a signature theme of Xi’s era, explicitly ties back to avenging the humiliations of the past. Xi’s hallmark Chinese Dream is essentially the dream of a strong China restored to its rightful status after a long historical eclipse. This entails not only wealth and military might, but also psychological security – being able to assert China’s interests without fear of foreign coercion. It is why, for example, Beijing is hypersensitive to foreign criticism of its human rights or political system: such criticism revives memories of past foreign “lecturing” and meddling. Sovereignty, in the Chinese formulation, means absolute non-interference by outsiders in China’s internal affairs. The national humiliation legacy also fuels a drive for self-reliance. The logic is straightforward – if foreign powers once exploited China’s weaknesses, then China must never be dependent on others for critical needs. This historical chip on the shoulder helps explain China’s immense investment in indigenous capabilities today, from defense industries to food security and advanced technology.

Crucially, China’s leadership does not frame its rise as an unprecedented “new” ascent but as a return to normalcy. As one analysis observes, the Chinese view their resurgence as a return to greatness from a century of decline, rather than a brand-new bid for dominance. This perspective breeds a strong sense of historical entitlement and patience. Unlike rising powers who lack past primacy, China sees itself as merely reclaiming a position it held for centuries in the pre-modern world – namely, the predominant power in Asia and a central actor globally. This restorative ambition carries deep emotional weight. It reinforces the CCP’s legitimacy at home (the Party delivered salvation) and shapes China’s posture abroad (it seeks respect commensurate with its heritage). The narrative of humiliation and rejuvenation drives home a strategic imperative: China must be powerful enough that no one can ever humiliate it again. In service of that goal, almost any sacrifice or effort is justified.

Box 1: Realism in Action—Contrasting 19th-Century Power Shifts Between East and West

Scope & Definitions

This case study explores how realism—the international relations theory that states prioritize survival and power—played out among Asian empires (Qing China, Tokugawa/Early Meiji Japan, and Mughal/Post-Mughal India) confronted with Western powers rising through industrialization. “Century of Humiliation” commonly references the period from the First Opium War (1839–1842) to the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, during which Qing China faced a series of defeats and concessions to foreign interests. India, likewise one of the world’s leading economies by total GDP in the early 18th century, became a British colony. Japan, meanwhile, escaped a similar fate through rapid modernization following the Meiji Restoration (1868), enabling it to compete with Western powers.

Historical Overview & Key Milestones

- Pre-Industrial Balance (circa 1700–1800)

- Asia’s Leading Economies: According to estimates by economic historian Angus Maddison, China and India together comprised 40–50% of world GDP in the early 18th century. They were predominantly agrarian but had significant handicraft sectors (textiles, ceramics, etc.).

- Western Empires on the Eve of Change: European powers (especially Britain, France, and later Germany) were still in an emergent industrial phase, but about to undergo dramatic transformation due to technological advances.

- Industrial Revolutions & Western Surge (late 18th–19th century)

- Technological Leap: Steam power, mechanized textile production, steelmaking innovations, and modern transport (railways, steamships) propelled European (and later U.S.) economies to global dominance.

- Military Innovations: Rapidly advancing artillery, breech-loading rifles, and iron-hulled warships outclassed older Asian armies and navies, giving Western empires coercive leverage on distant shores.

- China & India Under Pressure

- Qing China: Entered the 19th century with a large share of global GDP but lacked modern industrial capacity. Repeated military defeats (Opium Wars, Sino-Japanese War) led to “unequal treaties” and territorial concessions.

- India: The Mughal Empire had been in decline since the early 18th century; the British East India Company progressively took control, culminating in the British Raj in 1858. By the end of the 19th century, India’s share in global GDP declined sharply, and it became a source of raw materials and a market for British manufactures.

- Japan’s Divergent Path

- Tokugawa Isolation: Japan maintained a near-sealed border policy (sakoku). Western “gunboat diplomacy,” notably by the U.S. Commodore Perry (1853), forced Japan to open select ports.

- Meiji Restoration (1868): Japan’s new leadership embraced rapid Westernization—adopting European-style militaries, bureaucracies, and industrial technologies. By the 1890s, Japan revised or ended many unequal treaty terms; by 1905, it had defeated Imperial Russia in war, signaling its arrival as a modernized power.

Key Metrics Illustrating East–West Power Divergence

- Global Manufacturing Shares

- China: Circa 1800: ~30% of world manufacturing; by 1900: <10% (varies by source).

- India: Circa 1750: ~24–25% of world manufacturing (especially textiles); by 1900: <3%.

- Britain: Rose from ~2% of global manufacturing output in 1750 to around 20–25% by 1870 (the “workshop of the world”).

- GDP Ratios & Population

- China & India: Held major shares of world GDP (40–50% combined in 1700), but by 1913, their combined share had fallen to ~10–15%, though they still accounted for a large proportion of global population.

- Britain & U.S.: By 1900, the U.S. and British economies outproduced entire continents, a direct product of industrial capacity and overseas colonial/market networks.

- Military/Technological Gaps

- Steam & Steel: By mid-19th century, Britain and France had steam-powered ironclads, rifled artillery, and advanced logistics; Qing China’s fleet was still largely wooden junks, and Indian principalities used outdated weaponry.

- Railways & Telegraph: Rapid deployment of these networks in Europe and North America exponentially improved troop movement and coordination. Japan adopted similar technologies post-1868, while China and India lagged under fragmented or colonial railroad systems.

- Paths to Modernization

- Japan: Between 1870 and 1910, industrial output soared, literacy improved, and new factories proliferated. By the early 20th century, Japan matched or exceeded some Western powers in steel tonnage and naval capabilities.

- Qing China & Colonial India: Internal strife (Taiping Rebellion, regional warlordism) and external subjugation (unequal treaties, colonial rule) hampered domestic efforts to build modern factories and armies on the same timeline.

Realist Interpretation

The comparison underscores a core realist premise: states that fail to keep pace in economic and military capabilities risk losing sovereignty or influence to more advanced rivals. Western powers, fueled by industrial revolutions, rapidly escalated their power, thus dominating under-industrialized states in Asia. Japan avoided the fate of China and India by pivoting to modernization in time to challenge Western empires—and, later, to pursue regional hegemony itself.

For China and India, the historical lesson is stark: having once held top positions in global GDP, they were dramatically outstripped by Western industrialization. China’s subsequent “century of humiliation” and India’s colonization exemplify the severe consequences of a relative power vacuum—outdated militaries and inadequate modernization left them vulnerable to imperialism. Japan’s divergence shows that states can alter their fate by rapidly adapting to new technological and industrial paradigms.

Uncertainties & Limits of the Data

- Historical Accounting: GDP estimates before the 20th century rely on incomplete records and varying methodologies (e.g., Angus Maddison’s reconstructions). Discrepancies arise from differences in data sources and definitions (e.g., what counts as “manufacturing” vs. “agricultural processing”).

- Underestimation of Informal Sectors: Traditional economies in China, India, and Japan featured substantial cottage industries that do not map cleanly onto modern manufacturing measures.

- External vs. Internal Decline: While Western encroachment was a major factor, internal fragmentation, social upheaval, and leadership choices also strongly influenced how quickly China and India lost ground—and how swiftly Japan rose.

- Counterfactuals: Even robust data on trade volumes or steel tonnage cannot predict how different policies—earlier rail development, deeper foreign alliances—might have changed outcomes in Asia. These metrics are proxies, illustrating the broader shift in power, but cannot fully capture qualitative aspects of governance, culture, and strategic decision-making.

Conclusion

Contrasting the trajectories of China, India, and Japan with contemporary Western powers in the 19th century highlights the realist imperative for states to remain technologically and militarily competitive—or risk subjugation. Despite large populations and significant wealth, both Qing China and Mughal/Post-Mughal India were overwhelmed by Western powers’ industrial might. By contrast, Japan’s Meiji-era modernization enabled it to stand as a near-peer competitor by the close of the century. For China today, these historical echoes of vulnerability motivate a relentless drive for technological and economic self-sufficiency—a rational, risk-aware response rooted in the painful lessons of the past.

The Communist Ideology and Leadership Values

While history and tradition influence China’s worldview, the Marxist-Leninist ideology of the CCP provides the organizational framework for its strategic action. The CCP is an avowedly Leninist party – centralized, disciplined, and convinced of its vanguard role. This translates into a leadership culture that values control, unity of purpose, and ideological loyalty. Over time, the CCP has blended its Marxism with Chinese nationalism and selective traditional ideas, forging a unique state ideology under leaders like Mao, Deng, and now Xi.

Xi Jinping Thought, the guiding doctrine of the current era, is often described as an eclectic synthesis. It “merges party-centric nationalism, Leninism, Maoism, Legalism, and Confucianism” into a Sinicized socialism that serves CCP rule. In practice, this means that Xi’s worldview is intensely Party-centric and power-centric. One of Xi’s oft-repeated principles is that “government, military, society and schools – east, west, south, north, and center – the Party leads them all.” The primacy of the CCP is non-negotiable; everything else, from economic reforms to foreign ventures, must reinforce the Party’s leadership. This reflects Leninist DNA – the state is an instrument of the Party, and maintaining internal cohesion is paramount. Dissent or pluralism are seen as existential threats (echoing lessons from the Soviet collapse, which Chinese leaders attribute to ideological laxity). Thus, CCP ideology molds strategic behavior by prioritizing regime security above all. Policies are crafted not only for external effect but also to shore up domestic stability and Party legitimacy.

A key aspect of CCP ideology is its long-term orientation. Communist ideology traditionally involves long-range historical thinking – the eventual triumph of socialism, etc. In China’s case, this merges with indigenous long-termism. From Mao’s era onward, Chinese leaders have issued expansive multi-decade visions (e.g. Mao’s vision of catching up to the West, Deng’s “three-step” development plan by mid-21st century, etc.). Under Xi, the CCP has set explicit centennial goals: by 2021 (100 years since the CCP’s founding) China should become a “moderately prosperous” society, and by 2049 (100 years of the PRC) China should be a “great modern socialist country” – essentially, a rich, powerful nation that is a global leader. Achieving these goals is framed as the Party’s historic mission. In Xi’s words, from now until mid-century, the central task is “to build China into a great modern socialist country in all respects and achieve national rejuvenation.”. This long-term mission-focus instills in Chinese policymakers a mindset of strategic patience and discipline. They are willing to work methodically over decades, avoiding rash moves that could derail their trajectory.

The values cherished by the leadership – discipline, patience, and holistic thinking – also derive from this ideological brew. Confucian influences reinforce respect for hierarchy and order; Leninist practice demands strict obedience and unity; nationalism provides the motivational zeal to overcome hardships for the motherland. The result is a leadership ethos that is calculating yet resolute. Chinese officials are trained to think in terms of comprehensive national power – a composite index of economic, military, technological, and institutional strength. Every major policy is evaluated for how it contributes to enhancing this comprehensive power and moving China closer to its rejuvenation. Chinese policymakers emphasize a long-term strategy, focusing on gradual, future-oriented progress rather than short-term political cycles. In sum, CCP ideology imbues the leadership with a strategic big-picture perspective, where short-term setbacks are tolerable if the long-term trend is upward. It also places a premium on self-reliance and resolve: as true Marxist believers in dialectical struggle, the CCP elite expects challenges and opposition, and values the ability to “struggle” through difficulties by relying on the Party’s own strength.

One cannot overlook Mao Zedong’s enduring influence on leadership values as well. Mao’s ideological legacy taught the Party to be revolutionary, independent, and unafraid of isolation. His dictum of “regaining initiative by daring to struggle” remains part of Party lore. Xi has in fact revived some Mao-era ideological campaigns (like urging Party members to remember the spirit of the Yan’an years, or launching rectification drives to enforce loyalty). The through-line is a belief that political willpower and correct line can overcome material disadvantages. This thinking reinforces China’s confidence in facing off against a materially superior U.S. in areas like defense or tech: the CCP mindset is that through mobilization, unity, and creativity, China can catch up and surpass competitors. Ideology thus serves as a force multiplier – rallying the nation around grand projects and stiffening resolve when encountering external pressure.

In summary, historical memory and ideological doctrines deeply shape China’s strategic calculus. Confucian and Legalist thought provide a native logic for authoritarian stability and pragmatic statecraft; the trauma of past weakness instills a drive for power and respect; and CCP Leninist ideology supplies the long-term, centrally coordinated approach to achieving those ends. Together, they forge a leadership perspective that sees the world through the lens of power politics and national destiny. Chinese leaders perceive global affairs as a Darwinian arena where only the strong prevail and where China must methodically gather the levers of strength. Patience, of course, is a virtue in this scheme – because time is on China’s side if it plays its cards well.

Strategic Patience and the Long View

A striking feature of China’s rise has been its strategic patience. For much of the past four decades, China increased its power cautiously, often quietly, avoiding direct confrontation even as it built formidable capabilities. This patience is not incidental; it reflects conscious strategic guidance from the top. Deng Xiaoping’s famous maxim – “hide our capabilities and bide our time, never seek to take the lead” – became the credo of Chinese foreign policy in the post-Mao era. Deng uttered these words as the Cold War waned, advising that China should remain modest abroad while focusing on internal development. The idea was that China needed a peaceful external environment to grow stronger, and it should not provoke a balancing coalition prematurely by flaunting its ambitions. Subsequent leaders Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao largely heeded this “low-profile” strategy, emphasizing economic integration and “peaceful development” as China’s mantra.

The effectiveness of this approach is evident: for years, China benefited from globalization, attracted foreign investment and technology, and did not trigger severe counter-reactions, all while rising from a poor country into the world’s second-largest economy. Patience is ingrained in Chinese strategic culture partly via Confucian teachings (which value deliberation and restraint) and partly via realpolitik calculations. As long as the balance of power was unfavorable, it made sense for China to avoid risky assertiveness. Instead, it leveraged interdependence and the allure of its market to accumulate influence almost by stealth.

However, strategic patience does not mean passivity. Even during the “bide our time” years, China was steadily expanding its influence—joining and shaping international institutions, courting developing countries, and methodically modernizing its military. The patience was about timing and tactics, not abandoning ultimate objectives. Today, under Xi, China has become far more confident and assertive, indicating that its leadership believes the era of hiding is over. Xi Jinping has declared that China is now “moving closer to center stage” in world affairs. Still, the long-term orientation persists. Beijing thinks in decades, not months, when it lays plans for technological self-reliance or naval expansion. There is a prevailing sense that China can and will outlast Western democracies in strategic endurance. A frequently cited notion in Chinese discourse is that the West, especially the United States, suffers from short-term thinking and political cycle whims, whereas China’s one-party system allows it to plan to 2035, 2049 and beyond with continuity.

Chinese leaders also believe they are witnessing an irreversible power transition in the international system – one that they can navigate to their advantage if they remain steady. Xi Jinping and his strategists often speak of the current era as one of “great changes unseen in a century,” implying that the unipolar US-led order is breaking down and multipolarity is emerging. From Beijing’s perspective, this is an opportunity requiring strategic patience: if China avoids catastrophic conflict and continues strengthening itself, time and historical trends will weaken the U.S. position and elevate China. Strategic policy frameworks project China’s ascent to global prominence as part of its developmental trajectory, amid broader assessments of evolving international power structures. This confidence, noted by outside observers, reinforces patience – why take reckless action if one is on course to win by endurance? It also fosters a willingness to absorb short-term pain (like tariffs or sanctions) as temporary hurdles in a long game.

At the same time, patience has its limits, especially on core sovereignty issues. On Taiwan, for instance, Chinese leaders exhibit strategic patience (preferring eventual peaceful reunification) but also communicate that unification cannot be delayed indefinitely. They calibrate their actions (military drills, diplomatic isolation of Taiwan) to incrementally shift the status quo in their favor without triggering war – a patient salami-slicing approach. Yet Xi has tied resolving the Taiwan question to the rejuvenation goal, implying a determination to see progress on it by the 2049 timeline. Thus, even patience is bounded by the larger historical mission the CCP has set.

In sum, China’s long view manifests as gradualism in execution but boldness in vision. The state may spend years perfecting a technology or establishing footholds in global markets before unveiling its strength. It is a strategic tradition that values sequential advancement – achieve one level of development, then proceed to the next, each step building on the last. This is reminiscent of ancient Chinese wei qi (Go) strategy: encircle and accumulate advantages patiently until the balance tips decisively. By internalizing this approach, Chinese policymakers attempt to avoid impulsive adventures and instead shape the environment over time. The result is a foreign policy that can appear inscrutable or enigmatic to outsiders, because its moves are often subtle or indirect, aimed at long-term effects rather than immediate wins.

As we shall explore, this strategic patience underlies China’s methodical pursuit of technological supremacy and economic security. While the West sometimes sees Chinese initiatives like the Belt and Road or industrial plans as sudden aggressive plays, they are in fact the product of long incubation and forward planning. Beijing’s grand strategy is akin to a marathon, not a sprint – and it is determined to set the pace.

From Mao to Xi: Evolution of Grand Strategy

China’s current grand strategy did not emerge overnight with one leader – it is the product of an evolution across successive eras of the People’s Republic, each building on the achievements and lessons of the previous. Since 1949, the PRC has had five paramount leaders (Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao, and now Xi Jinping), and each has faced different internal and external environments. Yet running through their tenures is a continuity of core strategic objectives: preserving CCP rule, safeguarding sovereignty, and restoring China’s great power status. What has changed are the strategies and policies to pursue those objectives, adapting to circumstances and China’s growing capabilities. Tracing the arc from Mao to Xi reveals how China’s grand strategy has been refined and why today’s approach looks more assertive – it rests on the cumulative gains of prior generations.

Mao Era: Sovereignty, Survival, and Revolutionary Strength

Mao Zedong (1949–1976) laid the foundational security and sovereignty framework for the PRC. Emerging from a century of foreign domination and civil war, Mao’s primary strategic concern was to cement China’s independence and regain control over its territory. He succeeded in unifying most of historical China (integrating Tibet and Xinjiang, for example) and asserted sovereignty by intervening in the Korean War (1950–53) to repel U.S. forces from China’s doorstep. The Korean War victory – costly as it was – sent a clear message: the new China would fight to defend its core interests even against a superpower. This bravado shaped China’s strategic ethos of standing up to stronger foes when necessary. Mao famously declared that China would “not fear nuclear war” at a time when it lacked any atomic weapons; such rhetoric underscored a resolve to never bow again.

Under Mao, China’s strategy was also driven by revolutionary ideology. Aligning with the Soviet Union initially, Mao aimed to build socialist strength but soon split with Moscow, determined that China pursue an independent path (the Sino-Soviet split of the 1960s). Isolated with two superpower rivals (U.S. and USSR), Mao adopted a strategy of “leaning to one side” then switching: he balanced against the greater threat (Soviet Union) by rapprochement with the U.S. in the early 1970s. This geopolitical flexibility – shocking the world by the Nixon-Mao détente – showed that Chinese leaders would make pragmatic shifts to secure the nation’s position, ideology notwithstanding.

Internally, Mao focused on self-reliance (自力更生). Sanctions and embargoes in the 1950s taught China to develop its own industrial and defense base. Mao launched major projects to ensure China could produce strategic goods like steel, machinery, and eventually nuclear weapons (successfully tested in 1964) without outside dependence. The concept of “self-reliance” in strategic industries dates to this period. Mao’s era was tumultuous (the Great Leap Forward, Cultural Revolution) and economically damaging, but it forged the foundations of a sovereign state with basic industrial and military capabilities. Mao also ingrained a mindset of continuous struggle – politically and against foreign threats – which still influences China’s assertiveness under pressure.

In summary, Mao contributed the essentials of hard sovereignty: territorial integrity (except Taiwan, which remained unresolved), a nuclear deterrent, and a defiant national spirit. He demonstrated that China would sacrifice and endure hardship rather than submit – an attitude that bolsters China’s bargaining posture even today. However, Mao’s China was still relatively weak and poor; he achieved security but not prosperity.

Deng Era: “Reform and Opening” and Hiding Strength

Deng Xiaoping (1978–1989 as paramount leader, though he influenced into the 1990s) revolutionized China’s strategy by pivoting from class struggle to economic development as the national priority. Deng famously said “development is the hard truth” – recognizing that without economic and technological strength, China could never truly be powerful. Thus began the era of Reform and Opening Up. Deng’s strategic genius was in marrying a pragmatic internal strategy (market reforms to build wealth) with an external strategy of integration into the global order to access capital, technology, and markets.

Deng assessed that the global environment after the Cold War would be favorable for Chinese development – and that China should seize the opportunity. His guidance to “keep a low profile and never claim leadership” encapsulated his foreign policy: avoid ideological crusades, join international institutions, trade with all sides, and reassure the world of China’s benign intent. This approach was codified in the so-called “24-character strategy” attributed to Deng: “observe calmly; secure our position; cope with affairs calmly; hide our capacities and bide our time; be good at maintaining a low profile; and never claim leadership.” It was a prescription to not alarm the status quo powers while China rebuilt its strength. During Deng’s time and well into the 1990s, China indeed focused inward on economic growth, largely avoiding foreign adventurism.

Nonetheless, Deng was not shy about protecting core interests. He authorized China’s 1979 war against Vietnam (a brief but bloody punitive expedition) to check Soviet-aligned Vietnam’s influence in Southeast Asia – demonstrating a readiness to use force regionally. But he quickly refocused on development after, essentially compartmentalizing security actions so they didn’t derail the main mission of growth. Deng’s governance saw the beginning of China’s defense modernization (with a downsized but more professional military) and the pursuit of science and education as keys to power. In the early 1980s, forward-looking officials like Jiang Zemin (then a minister) stressed that information technology would be the “strategic high ground” of international competition and that China must catch up. Deng’s administration launched programs to boost science and technical training, sent students abroad, and courted foreign investors. This was the start of China leveraging globalization to enhance its national power.

A notable strategic decision by Deng was the handling of Hong Kong and Macau – negotiating their return from Britain and Portugal through the “one country, two systems” formula. Deng prioritized sovereignty recovery through diplomacy when possible (peaceful reunification), reserving force mainly for when negotiation failed (as with Vietnam or in facing down provocations like 1980s skirmishes in the South China Sea). Taiwan remained unresolved, but Deng opened indirect talks and proposed the one country, two systems model for a future peaceful unification – again taking a long view.

In sum, Deng’s era contributed economic power to China’s grand strategy and set the template of strategic patience. He shifted China from a mainly military-industrial concept of power to a broader, comprehensive national power concept that emphasized GDP growth, technological advancement, and stable foreign relations. Deng firmly subordinated military expansion to economic priorities (famously cutting military budget shares). This was not pacifism but prioritization: he understood that wealth is the foundation of strength. The legacy is that by the early 2000s, China’s economy was booming and interlinked with the world, providing the material base for the more assertive policies of later years.

Jiang Era: Integration into the Global Economy and Technological Catch-up

Jiang Zemin (1989–2002 as CCP General Secretary) inherited a China on the rise but facing post-Tiananmen sanctions and suspicion. Jiang’s task was to normalize China’s global relations and continue economic expansion, while firmly keeping the CCP in control domestically. He largely succeeded: the 1990s saw China join the global economy at unprecedented scale, culminating in accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. This integration was a strategic choice – by locking itself into global trade rules, China gained access to vast export markets. The wager was that the benefits to national power would outweigh the risks. Indeed, WTO entry turbocharged China’s export industries and manufacturing ascent, fueling double-digit GDP growth that financed other elements of national power.

Jiang’s era was also marked by major strides in science and technology development. China’s industrial modernization accelerated through strategic research initiatives: the 863 Program (launched 1986 for high-tech development) and the 973 Program (established 1997 for basic scientific research), which complemented the industrial priorities outlined in the 1995 Ninth Five-Year Plan. The government poured resources into expanding higher education and research institutes. Jiang himself, having a technocratic background, stressed the need to “catch up with advanced levels” especially in information technology. Under his watch, China built its first modern internet infrastructure and invited tech multinationals to set up shop, learning from them. By early 2000s, Chinese firms were emerging in telecom (Huawei, ZTE) and consumer electronics. Jiang thus presided over the incubation of indigenous tech capabilities that form the backbone of today’s innovation drive.

On the strategic front, Jiang continued the low-profile foreign policy but began to test China’s newfound clout in regional affairs. In 1997, during the Asian Financial Crisis, China notably did not devalue its currency (a responsible stakeholder move) and provided some support to neighbors, which earned goodwill. Jiang also pursued better relations with Russia (signing a partnership in 1996) and with ASEAN, laying groundwork for later regional influence. Militarily, the 1995–96 Taiwan Strait Crisis – where China conducted missile tests and the U.S. sent carriers – was a wake-up call. Jiang’s government accelerated military modernization after seeing the gap in power projection relative to the U.S. Still, the overall thrust was to avoid direct confrontation and focus on “comprehensive national power” accumulation quietly.

Importantly, Jiang’s era saw Hong Kong’s handover in 1997 and Macau’s in 1999, peacefully achieved, which boosted national pride and CCP legitimacy. It reinforced the narrative that China was shedding the last vestiges of humiliation (colonial enclaves) through patient negotiation, not war – a vindication of Deng’s approach. Taiwan remained tense (especially with pro-independence sentiment rising there), but China issued a white paper in 2000 reiterating a preference for peaceful unification while not renouncing force.

By the early 2000s as Jiang yielded to Hu Jintao, China had transformed into a major trade power with growing financial resources, a more modern military, and expanding diplomatic influence – all without fundamentally upsetting the global order. This was strategic success: China was stronger but not yet seen as a systemic threat by the West, which was preoccupied with the War on Terror. Jiang thus passed to his successor a country far more capable than a decade prior, and integrated enough to have stakes in the existing system.

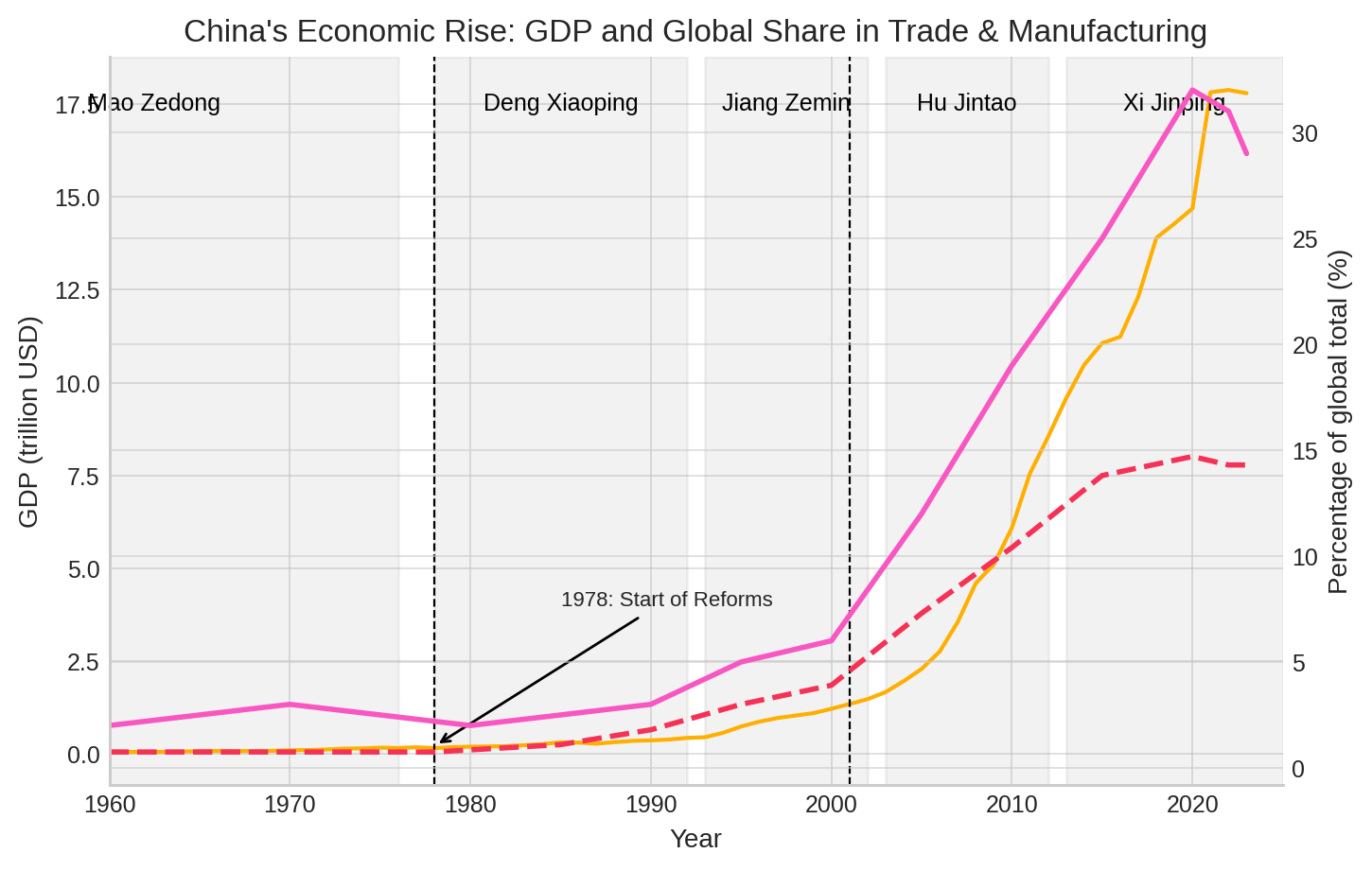

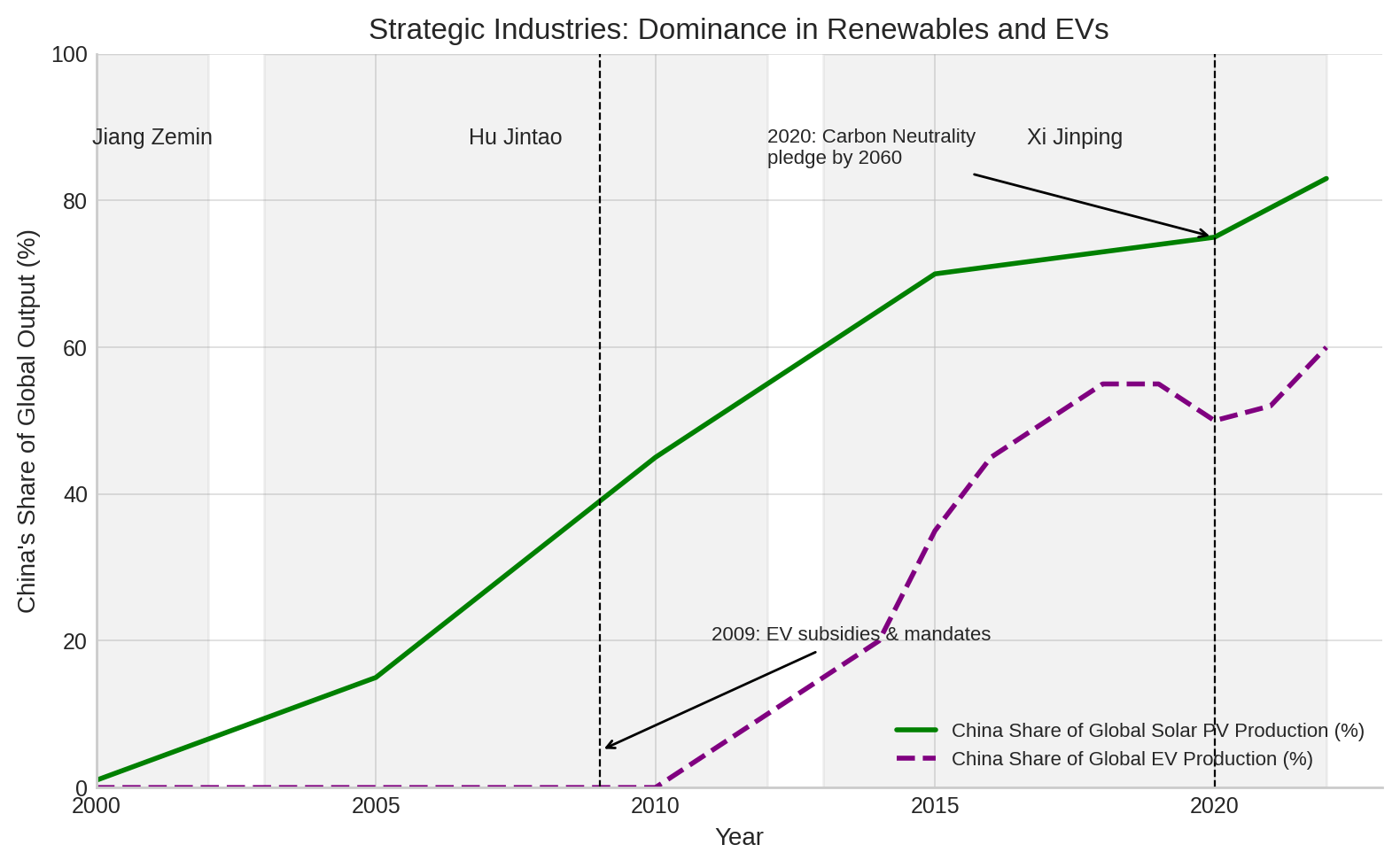

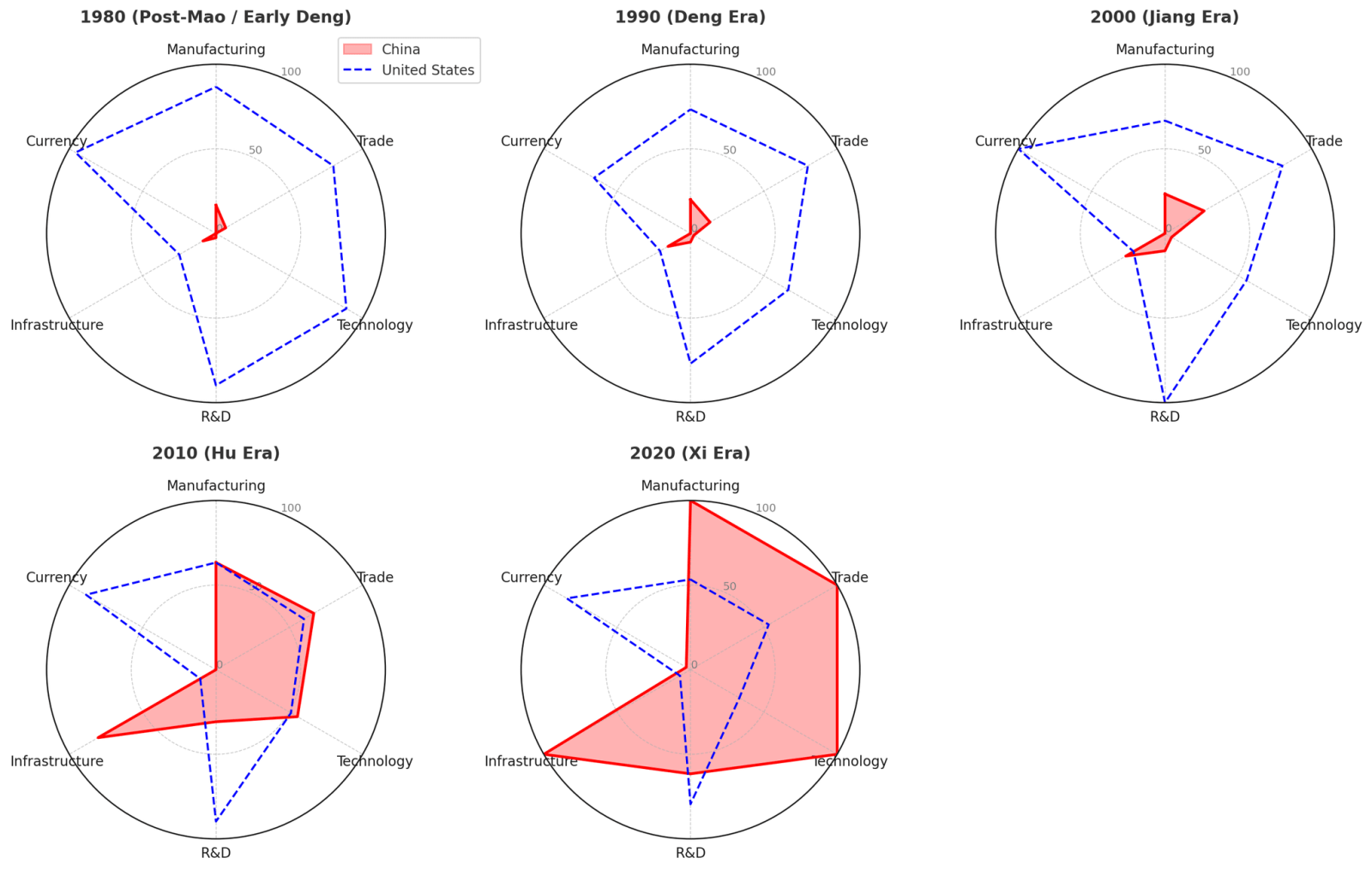

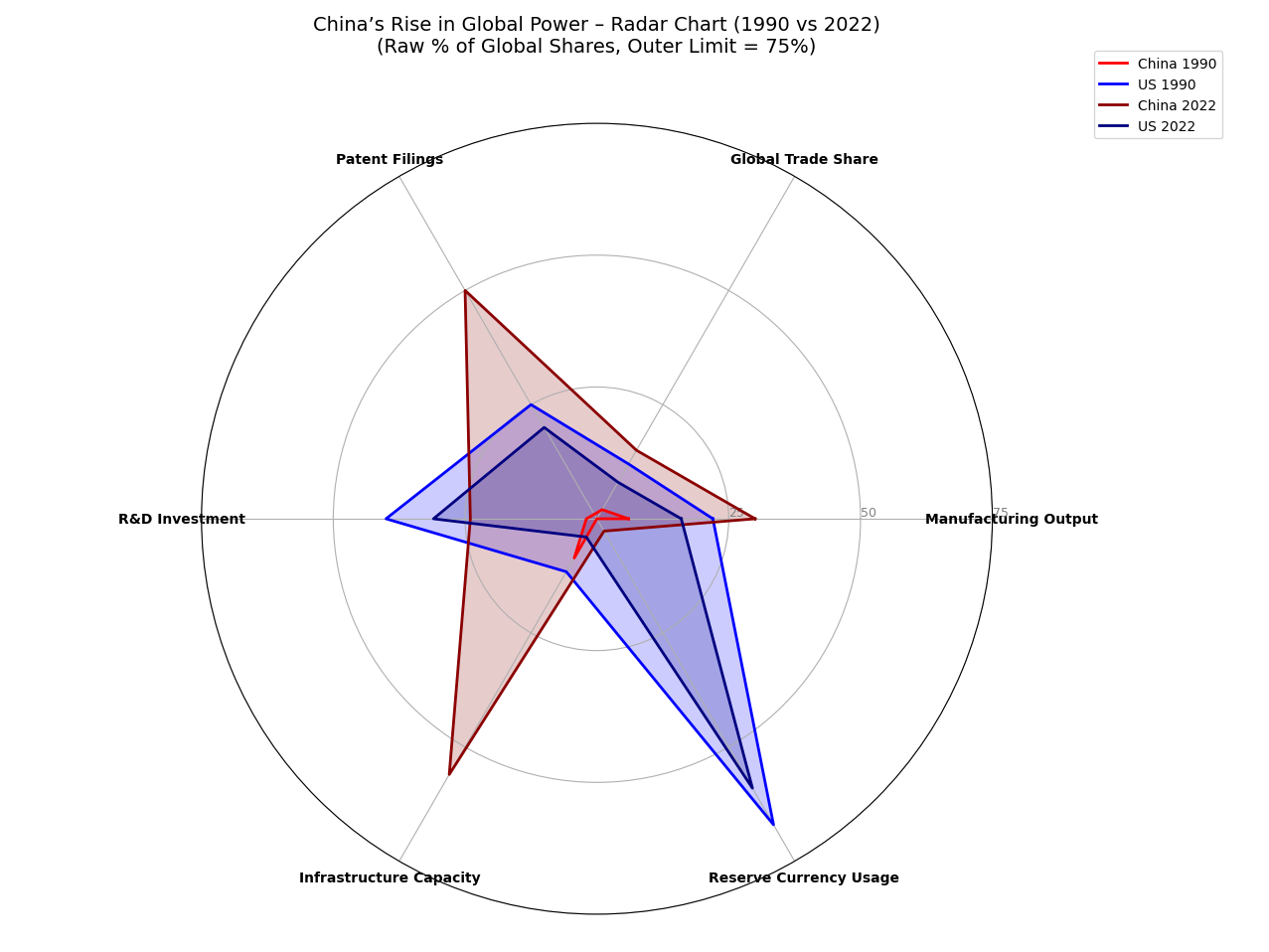

Economic Might – From Backwater to Powerhouse

China’s GDP soared from virtually negligible levels under Mao to $17.8 trillion in 2022, second only to the U.S. Deng Xiaoping’s Reform and Opening (1978) ignited explosive growth – by 2001 (WTO entry) China was the “workshop of the world.” As the chart shows, China’s share of global manufacturing output surged from under 5% in 1990 to roughly 30% by 2020, eclipsing all rivals. Likewise, its share of world merchandise exports climbed from ~2% in 1990 to 14–15% today. These gains reflect deliberate policy shifts: Deng prioritized economic development over ideology, spurring double-digit growth in the 1980s–90s. WTO accession in 2001 then supercharged China’s export machine (note the sharp post-2001 rise). By Hu Jintao’s era, China surpassed Germany, Japan, and finally the U.S. to become the #1 manufacturing nation and trading power. Today under Xi Jinping, China produces one-third of global manufactures and 15% of world exports, up from almost nil decades ago – a dramatic elevation of economic clout.

China’s Economic Rise across eras – GDP (yellow, left axis) vs. China’s share of world manufacturing output (pink, % right axis) and exports (red, % right axis). Major inflection points like 1978 (reforms) and 2001 (WTO entry) are annotated. Sources: ChinaPower Project – CSIS, World Bank.

Hu Era: “Peaceful Development” and Steady Assertiveness

Hu Jintao (2002–2012) presided over what was arguably the golden decade of China’s rise – a period of high growth, successful 2008 Beijing Olympics (signaling China’s arrival), and relatively calm external relations early on. Hu’s official line was that China’s rise would be a “peaceful development”, emphasizing that China sought a “harmonious world” with win-win cooperation. This slogan was aimed at assuaging fears of a “China threat.” Underneath the rhetoric, however, China under Hu became more proactive internationally as its power expanded.

Economically, China surpassed Japan in 2010 to become the world’s second-largest economy. It began investing abroad heavily (the “Going Out” strategy where state firms secured energy, minerals, and built infrastructure overseas). Hu’s government initiated the concept of the “Belt and Road” in embryonic form through infrastructure investments in Central Asia and Pakistan’s Gwadar Port, even though the BRI as a term came later under Xi. The idea that China could export capital and construction know-how abroad to gain influence took root in Hu’s time.

Technologically, Hu’s era saw massive expansion in innovation capacity. In 2006, China launched the National Medium- and Long-Term Program for Science and Technology Development (2006–2020), which set goals for becoming an “innovation-oriented society” and reducing reliance on foreign technology. This plan introduced targets for “indigenous innovation” and listed “strategic emerging industries” such as biotech, new energy, IT, etc., foreshadowing later initiatives. The 11th and 12th Five-Year Plans (covering 2006–2015) included these tech priorities. In effect, Hu’s administration institutionalized the drive to boost R&D, leading to China dramatically increasing its patent filings, academic research output, and the domestic tech industry’s capabilities. By 2012, companies like Huawei and Lenovo were globally competitive, and China had manned space missions and a burgeoning aerospace sector.

In foreign policy, while continuing a low-key posture generally, China under Hu did become more assertive after the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. Chinese leaders saw the crisis as a sign of Western weakness and a shifting balance. Hu’s second term (2008–2012) coincided with a more hardline stance on maritime disputes (e.g., more naval patrols in the South China Sea, incidents with Japan over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands). Some attribute this assertiveness to rising nationalism and the PLA’s growing clout, others to a calculated test of how far China could push as U.S. attention was divided. Still, Hu largely avoided direct military conflict and participated in global governance (such as G20 summits, climate talks) as a responsible major power. Hu also launched or joined multilateral forums like BRICS, projecting a vision of multipolarity and the Global South’s rise.

One conceptual contribution of the Hu era was the idea of a “Harmonious World” – calling for mutual respect and reform of the international system to be more equitable. This was in line with earlier multipolarity ideas championed by Chinese diplomats since the 1990s. Essentially, China was articulating a counter-hegemonic narrative softly: that the world should not be dominated by one superpower (the U.S.), but rather powers big and small should have a say (a thinly veiled reference to elevating China’s role). This set the stage for Xi to more bluntly assert a Chinese vision for world order.

To sum up, Hu Jintao’s era consolidated the fruits of Deng and Jiang’s strategies. China became wealthier, technologically stronger, and diplomatically more influential – to the point where it could begin setting the agenda in some areas. Continuity was evident in the emphasis on economic growth and stability, but change was seen as China started to flex its muscles in its near-abroad and to speak with a more confident voice on the global stage. By 2012, China had arrived at a level of power where the long-held goal of national rejuvenation seemed within reach. It was at this juncture that Xi Jinping took the helm and ushered in a new chapter.

Box 2: The 2008 Financial Crisis—A Strategic Inflection Point Emboldening China’s Global Posture

(How the West’s Financial Meltdown Accelerated Shifts in Power Politics)

Core Message

When the 2008 U.S.-centered financial crisis hit Western economies, China emerged comparatively unscathed and even maintained around 9% growth in 2009, aided by a ¥4 trillion (≈$585 billion) stimulus. This stark divergence prompted a fundamental shift in Beijing’s worldview: the once-lauded Western model of free-market finance showed deep vulnerability, emboldening China’s confidence in its own “state-capitalist” approach. From that point onward, Chinese leaders pursued greater assertiveness in global affairs—accelerating the timeline they had envisioned for China’s gradual rise and powering new initiatives (BRI, AIIB) that challenge U.S.-led frameworks.

Key Observations

- Systemic Western Weakness Unmasked

- Major banks collapsed under subprime and derivatives crises, shattering the myth of highly efficient Western financial regulation.

- Chinese elites saw “Western preachings” (fiscal discipline, liberalization) upended by bailouts and quantitative easing.

- China’s Divergent Crisis Response

- China’s ¥4 trillion stimulus stabilized its economy quickly, confirming to CCP officials the efficacy of strong state intervention.

- 2009–2010: While Western GDP shrank or stagnated, China recorded robust growth—fueling internal claims that “our system works.”

- Altered Timeline for Multipolarity

- Pre-2008, Chinese doctrine expected a slow, multi-decade shift in power balance. Post-crisis, Beijing accelerated external ambitions—perceiving a window to expand influence as the West struggled.

- Chinese officials openly questioned U.S. financial leadership, shifting from cautious integration toward selective revisionism (e.g. pushing yuan internationalization, forming parallel institutions).

- Assertive Policy Shifts

- Maritime claims hardened (South China Sea expansions in 2009–10), reflecting confidence that the West was too preoccupied to respond decisively.

- Economic governance: China began spearheading alternatives to Bretton Woods institutions—like the New Development Bank (BRICS), AIIB—offering non-Western nations new financing options.

Lasting Impact

- Deepened Skepticism Toward Western Models

- The meltdown’s self-inflicted nature reinforced China’s belief that Western-led rules are neither stable nor inevitable—justifying China’s own governance and “mixed-market” approach.

- Structural Reassessment of Global Finance

- The G20’s elevation to the ‘premier forum for international economic cooperation’ signaled a broader redistribution of global influence, though the G7 retained significant governing power in many domains. China strategically contributed to IMF bailouts while advocating for quota reforms that would better reflect its growing economic weight.

- Path to a More Confident Global Role

- Post-crisis, Beijing felt vindicated in demanding reformed or alternative orders, intensifying efforts to shape regional norms (Maritime Silk Road, RCEP) and reduce reliance on U.S. financial systems.

Conclusion

The 2008 crisis hammered the West and underscored China’s resilience, marking a strategic pivot from cautious integration to a bolder agenda. While the meltdown undeniably fast-tracked Beijing’s external ambitions, multiple factors (including decades of economic growth and existing dissatisfaction with Western frameworks) also shaped China’s evolving posture. Coupled with stable domestic support, Beijing leveraged the meltdown to expand its economic influence and adopt a more assertive global stance, convinced the Western financial model was far less unassailable than once believed.

Xi Era: National Rejuvenation and Global Ambition

Xi Jinping (2012–present) represents a culmination and a bold acceleration of China’s grand strategy. Xi’s leadership framework since 2012 progressively advanced national rejuvenation objectives, with the ‘Chinese Dream’ concept emerging early in his tenure and the formal ‘New Era’ doctrine institutionalized by 2017. Whereas previous leaders maintained a low profile, Xi has been far more forthright about China’s ambitions. He has concentrated power domestically, reasserted Party control over all sectors, and taken a more assertive stance abroad. This does not mean Deng’s patient approach is entirely discarded; rather, Xi appears to believe that China has accumulated enough strength to openly execute the later phases of its long-term strategy.

Under Xi, China launched a series of high-profile strategic initiatives. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), unveiled in 2013, is a flagship foreign policy project aiming to connect Eurasia (and beyond) through infrastructure and trade networks with China at the hub. Similarly, Made in China 2025, announced in 2015, established specific self-reliance targets for China in ten critical advanced manufacturing sectors by 2025. Xi also introduced the concept of “Dual Circulation” in 2020 to reshape the economy for greater self-reliance. These initiatives, which we will explore in detail, underscore Xi’s approach of proactively shaping China’s external environment and internal capacities to achieve major power status. Unlike the quiet achievements of past decades, Xi’s programs are explicitly branded and promoted, even if that invites pushback. Indeed, the Western backlash to “Made in China 2025” (viewing it as a threat to their industries) led Chinese officials to speak less about it publicly after 2018, though the policies continue.

Ideologically, Xi has tightened CCP discipline and revived strongman leadership not seen since Mao. He abolished term limits and enshrined “Xi Jinping Thought” in the constitution, elevating his personal authority. This centralization is intended to ensure unity as China navigates more contentious waters internationally. Xi emphasizes that the Party must control all levers – a return to Leninist firmness after a period of somewhat more collective leadership under Jiang and Hu. The effect has been a more coordinated and assertive pursuit of strategic goals, as bureaucracies and industries are pressed into serving national objectives (for instance, private tech firms are compelled to align with state tech ambitions).

One of Xi’s hallmark themes is self-reliance in key technologies. He has repeatedly exhorted China to become “self-reliant and strong in science and technology”, especially after seeing the U.S. impose tech sanctions. This drive for autonomy is consistent with the long arc from Mao’s self-reliance, but Xi is pursuing it in cutting-edge domains like AI, semiconductors, aerospace, and green tech through massive state-led efforts. Another focus is the military: Xi has undertaken the most sweeping military reform in decades, aiming to turn the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) into a “world-class force” by 2049. This includes reorganizing command structures, investing in power-projection capabilities (like aircraft carriers, cyber and space assets), and developing “assassin’s mace” technologies to counter U.S. strengths.

Xi’s foreign policy is far more assertive in defending what China sees as its core interests. This includes building militarized islands in the South China Sea despite an international tribunal ruling against China’s claims, applying economic coercion on countries that cross China’s political red lines (such as trade restrictions on South Korea, Australia, Lithuania in various disputes), and clashing with India along the Himalayan border. China’s diplomats under Xi even adopted a more confrontational tone, dubbed “Wolf Warrior” diplomacy, actively pushing back against Western criticism and promoting China’s narrative aggressively. All of these actions reflect a leadership that feels entitled and obligated to assert China’s interests commensurate with its increased power.

Yet Xi’s China still emphasizes that it does not seek outright hegemony or conflict. The official line is that China wants a “community of common destiny for mankind”, implying win-win cooperation and a multipolar world where no single country (implicitly, not the U.S.) dominates. In Xi’s talks with foreign leaders and multilateral forums, he often couches China’s rise as beneficial for global peace and development. This dual messaging – hard power moves on the ground, but benign rhetoric in speeches – is classic in great power strategy, keeping options open and trying not to galvanize a united opposition prematurely.

It is clear that Xi’s boldness builds on the platform established by predecessors. As one expert observed, despite surface differences, Xi’s rejuvenation strategy shows a “high degree of policy continuity” with earlier principles of centralized rule and state-directed development. The key institutions (Party control, state-owned economic pillars) are the same; what’s changed is that China now has the means to challenge U.S. primacy in ways unthinkable in Deng’s time. Xi’s task is managing this challenge. So far, he has shown a willingness to take higher risks – for example, Xi did not shy from a trade war with the U.S. when challenged, betting that China could weather the pressure better than expected.

As of the mid-2020s, Xi’s China is in a more openly adversarial stance with the West, especially the United States, which is imposing sweeping restrictions to contain China’s tech rise. We can interpret this as the inevitable strategic collision that China’s long ascent was preparing for. Xi appears to believe that this is the time to push through and not back down, lest China’s rejuvenation be stymied. The CCP under him conveys confidence that they can eventually prevail in a prolonged great-power competition. Indeed, Xi and Putin of Russia have together proclaimed that the world is witnessing “changes unseen in a century” and that they (China and Russia) are driving these changes. This hints at a perceived partnership to accelerate multipolar trends, splitting U.S. alliances and accessing resources, as strategic analysts observe that China’s Russia partnership serves both resource security and geopolitical competition objectives.

In conclusion, each era from Mao to Xi contributed building blocks to China’s grand strategy. Mao secured independence and instilled resolve; Deng brought economic might and patience; Jiang integrated China globally and pushed technology; Hu maintained momentum and cautiously expanded influence; Xi is capitalizing on all of it to make the final stride toward great power status. The continuity is seen in the unwavering pursuit of strength and sovereignty; the change is in China’s growing capacity and willingness to assert itself. Now with Xi at the helm, China’s strategy has entered a phase of active strategic competition – still calculating and long-term, but increasingly direct in challenging the U.S.-led order. China’s leaders see this not as a break with the past, but as the fruition of a 75-year quest to make China great again.

Strategic Coordination of National Development

Central to China’s rise has been the CCP’s ability to coordinate national development strategies in pursuit of power. Unlike many countries where economic policy, industrial policy, and foreign policy are compartmentalized, China tightly intertwines them under a holistic strategic framework. The engine of this coordination is a tradition of state planning and state-directed development, adapted to modern challenges. Through instruments like the Five-Year Plans, mega-initiatives such as Made in China 2025, and vehicles like state-owned enterprises and the Belt and Road Initiative, China orchestrates its economic growth, technological advancement, and overseas expansion in concert. The goal is straightforward: to systematically build the pillars of national power – industry, innovation, finance, infrastructure – and leverage them for geopolitical advantage. In this section, we unpack how these mechanisms function from China’s vantage point as rational means to compete in a realpolitik world.

The Role of Five-Year Plans: Guiding a Strategic Economy

Five-Year Plans (FYPs) are a legacy of China’s socialist command economy, but they remain vital today as blueprints aligning the nation’s development with strategic objectives. Each FYP (approved by the National People’s Congress) lays out priorities for economic and social growth, targets for key sectors, and major projects. In the reform era, the plans have shifted from rigid production quotas to indicative guidelines and strategic targets. Nonetheless, they signal the state’s direction and mobilize resources accordingly.

In the context of grand strategy, FYPs allow Chinese leaders to set long-term agendas and ensure policy continuity. For instance, starting from the 11th FYP (2006–2010) through the 13th (2016–2020), there was a clear through-line emphasizing “indigenous innovation” and nurturing high-tech industries. These plans recognized that to ascend the value chain, China had to reduce reliance on foreign technology and develop its own capabilities in areas like electronics, biotechnology, advanced materials, and aerospace. The 12th FYP (2011–2015) formally listed “strategic emerging industries” including new energy vehicles, next-generation IT, high-end equipment manufacturing, etc., which directly presaged initiatives like Made in China 2025. Thus, the seeds for China’s current tech drive were planted in successive FYPs years ago, illustrating the state’s habit of incremental but relentless planning.

A prominent example is the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025), which reflects China’s response to a more hostile external environment. The 14th FYP elevates science and technology self-reliance as a “strategic pillar” of national development. It calls for breakthroughs in core technologies and specifically aims to achieve greater self-sufficiency in semiconductors, AI, biotech, and other frontier fields. The plan highlights a “growing urgency to protect China from external vulnerabilities” by reducing dependence on foreign tech and inputs. This was a direct reaction to events like the U.S. cutting off Huawei’s access to chips – the message: China must master these chokepoint technologies itself. The 14th FYP also formally incorporated the Dual Circulation strategy (more on that below), signaling a structural shift to bolster domestic economic loops to withstand decoupling or shocks.

We see, therefore, that FYPs act as vehicles for strategic adaptation. When global or domestic conditions change, new priorities are embedded in the plan, aligning the bureaucracy and industry with the leadership’s strategic intent. Because the plans cover five-year spans with outlooks often to 15 years (e.g., the 14th FYP document includes a vision for 2035), they bridge short-term actions with long-term goals. This disciplined planning culture – rare among large economies – gives China a way to marshal disparate efforts (provincial governments, SOEs, private sector) toward common targets like increasing R&D spending or achieving X% production of certain components at home.

From a realpolitik perspective, the FYP system is one of China’s advantages. It means the country can synchronize economic policy with strategic needs in a top-down fashion. For example, if leadership deems quantum computing critical for future security, they can incorporate that into the plan and suddenly funding, talent programs, and corporate incentives align to pursue it. Western commentators sometimes dub this the “whole-of-nation” approach, which can be formidable in rallying capabilities (albeit at the cost of some economic inefficiencies). Beijing sees this state-guided model as proven by China’s rapid ascent and as a necessity in competing with established powers. Chinese leaders invoking “concentrating forces” use an enduring socialist method that fuses central planning with market dynamics to unite government, industry, and research for strategic breakthroughs.

Made in China 2025: Climbing the Value Chain

No discussion of China’s coordinated strategy is complete without Made in China 2025 (MIC2025), the emblematic industrial policy initiative aimed at propelling China into the top ranks of advanced manufacturing. Launched in 2015, MIC2025 is essentially a roadmap for China to leap from being the world’s factory of low-tech goods to a technology powerhouse dominating high-value industries. It identified ten priority sectors, including advanced information technology, robotics, aerospace, marine engineering, new energy vehicles, power equipment, materials, biopharma, and more. The plan set specific benchmarks: by 2025, China intended to sharply increase domestic content in key components and materials (targeting 70% self-sufficiency in core components), and have Chinese firms achieve significant global market share in these industries.

From China’s perspective, MIC2025 is a rational strategy to avoid the “middle-income trap” and ensure national security. Relying on foreign suppliers for critical technologies (like semiconductors or aircraft engines) is seen as a strategic vulnerability – one that could be exploited by adversaries. Therefore, moving up the value chain and developing indigenous capabilities is about economic survival in the long run and strategic autonomy. Moreover, capturing high-tech industries is key to boosting productivity and incomes domestically; the leadership knows that China cannot prosper indefinitely on assembly-line labor and infrastructure spending alone. As such, MIC2025 was an offensive and defensive play simultaneously: build national champions in new industries to capture global markets (offense), and replace foreign tech in sensitive areas with homegrown versions (defense).

To Western countries, MIC2025 rang alarm bells because it openly signaled China’s intent to displace foreign competitors in cutting-edge fields. Beijing was somewhat caught off guard by the backlash. However, it’s important to frame MIC2025 in China’s own narrative. Chinese policymakers view industrial policy as a legitimate tool – after all, they point out, many of today’s rich countries used protection and subsidies in their own development phases. In the Chinese telling, the West enjoyed its decades of dominance in high-tech and now hypocritically wants to thwart China’s rise. Thus, pushing aggressively in advanced manufacturing is framed as restoring fairness and breaking Western monopoly, not malicious takeover. Internally, MIC2025 was promoted as the way to make “Chinese manufacturing” a mark of quality and innovation, not just low-cost mass production.

The implementation of MIC2025 involved massive state support. Government at central and local levels poured funds into research, provided subsidies and cheap loans to firms in target sectors, set up industrial parks and incubators, and facilitated acquisitions of foreign tech companies to gain know-how. A notable example is semiconductors: China invested tens of billions in domestic chip production since 2015, raising self-sufficiency from under 20% toward an initial 70% target by 2025, though current projections estimate ~30-35% amid technological hurdles and export controls. Similar pushes happened in electric vehicles (leading to many Chinese EV companies emerging) and renewable energy equipment (where Chinese firms already had a strong foothold).

By design, MIC2025 dovetailed with the Five-Year Plans. It was incorporated into the 13th FYP and continued in substance into the 14th, albeit less conspicuously termed due to foreign criticism. The core goals have not changed – in fact, they intensified under the pressure of U.S. sanctions. Beijing has effectively doubled down on the quest for tech independence, seeing MIC2025’s objectives as even more vital now that the U.S. is actively trying to lock China out of cutting-edge tech. One could argue MIC2025 succeeded in that it correctly foresaw the coming tech bifurcation and prepared China to some extent. Already by 2020, China had achieved significant progress in multiple MIC sectors: commanding the world’s largest high-speed rail network, leading global solar panel and battery manufacturing, and establishing Huawei as a major 5G equipment supplier despite market restrictions in several Western countries.

From a grand strategy lens, Made in China 2025 is the blueprint for building comprehensive national power in the industrial-technological domain. It coordinates with military modernization (many technologies like aerospace and AI have dual-use aspects) and with foreign policy (a technologically advanced China can wield more influence, e.g. offering its tech solutions to others). It also resonates with domestic politics – the narrative of becoming a cutting-edge economy boosts national pride and CCP legitimacy. Although external pushback forced Chinese officials to mention MIC2025 less, they have not abandoned it. They simply embed its aims into broader programs (like “manufacturing upgrade” in the 14th FYP). China mobilized roughly $300 billion in aggregate commitments by 2018 toward MIC2025-related sectors through multiple funding mechanisms, reflecting sustained industrial policy ambitions.

In essence, Beijing is executing what many late-developing powers attempted: a state-led surge to catch up and surpass incumbents in key industries. Historically, few have succeeded at the scale China attempts. But China’s leaders bet that with sheer market size (a billion-plus domestic consumers), huge talent pool, and authoritarian coordination, they can force their way into the top tier. If successful, MIC2025—together with its evolving successor policies— would not only make China rich; it would give it economic leverage worldwide (imagine global dependence on Chinese high-tech goods and standards, much as the world once depended on Western or Japanese tech). It’s a vision of economic dominance translating into geopolitical clout – which is exactly why they pursue it, and exactly why others resist it.

Dual Circulation: Hedging Against External Dependence

A more recent strategic concept is “Dual Circulation,” introduced by Xi Jinping in 2020. Dual Circulation is essentially an economic rebalancing strategy wherein China will “rely mainly on internal circulation” (domestic production, distribution, and consumption) while external circulation (exports and foreign investment) plays a supportive role. In simpler terms, it means boosting domestic demand and self-contained supply chains so that China is less vulnerable to external shocks or pressures. This strategy emerged as a response to the turbulent international environment – notably the U.S.-China trade war and tech sanctions – that exposed how over-reliance on foreign markets and technologies could be a strategic liability.

From Beijing’s viewpoint, Dual Circulation is a prudent hedge in a world where globalization is no longer seen as guaranteed or apolitical. By strengthening the domestic cycle of its economy, China aims to ensure that even if exports face barriers or if key imports (like semiconductors or energy) are cut off, the country can still sustain growth and development. The timing was telling: Xi first raised the idea in mid-2020 as the pandemic disrupted global supply chains and U.S. hostility toward China’s tech sector escalated. It was later codified in the 14th Five-Year Plan as a guiding principle.

Dual Circulation does not mean China is closing off its economy – rather, it’s about achieving a better balance. For decades, China’s growth leaned heavily on exporting to the West and importing high-tech inputs. Now, the leadership wants to cultivate robust domestic consumption to drive growth (so it’s not at the mercy of foreign demand cycles), and to develop domestic sources for key technologies and components (so it’s not at others’ mercy for supplies). Internally, this involves policies to raise household incomes, improve social safety nets (so people will spend more), and encourage innovation and local supply chain integration. Externally, China still seeks trade and investment, but in a way that complements the domestic loop – for example, attracting foreign companies to manufacture in China for the Chinese market, and pushing Chinese companies to climb up value chains in global markets.

Strategically, Dual Circulation aligns with the drive for self-reliance in critical sectors that we’ve discussed. It also connects to security concerns. For instance, energy security: China imports a lot of oil/gas; dual circulation would emphasize domestic energy production and renewables, plus diversified import partners, to avoid being strangled by a blockade. Or in finance: reducing reliance on the U.S. dollar system via promoting use of the RMB and developing Chinese financial institutions (so sanctions have less bite). It’s about creating an ecosystem where China can withstand decoupling attempts. As one analysis put it, the strategy aims to “reduce China’s vulnerability to external shocks” and hostile actions.

One concrete component is tech innovation as part of internal circulation. Under the dual circulation strategy, China seeks to boost tech innovation and help domestic firms advance up the global value chain. That means efforts like MIC2025 and the 14th FYP’s tech initiatives are integral to dual circulation – because achieving domestic loops requires having domestic tech. If China can make its own high-end chips, machines, and software, then its economy is far more self-sustaining. Dual circulation essentially provides the macroeconomic rationale to continue heavy investment in innovation and industry upgrade.

Another component is expanding domestic markets – which also has a global geopolitical angle. A China with a giant consumer market that is relatively self-sufficient and thriving can use access to that market as leverage. For example, in the future, foreign companies or countries may find the Chinese market so crucial that they are reluctant to cross Beijing politically for fear of losing access. We already see glimpses of this (e.g., how the prospect of Chinese retaliation can temper some governments’ actions). Thus, while on the surface dual circulation is economic, its success would translate into greater strategic autonomy and influence for China.

In Chinese official narrative, Dual Circulation is portrayed as a natural evolution given China’s growing domestic demand and a necessary adaptation to “changes in the international environment.” It’s framed positively – focusing on domestic development – rather than as an anti-West move. But implicitly, it is about de-risking on China’s terms: reducing one-sided dependencies while still benefiting from globalization where convenient. If Western decoupling cuts China off from some external circuits, China’s answer is to strengthen its internal circuit and find new external partners (for instance, leaning more on trade with ASEAN, Africa, Latin America, and Belt and Road countries to substitute some U.S./EU links).

The interplay of internal and external circulation is also worth noting. External circulation isn’t abandoned; it’s to be harnessed to improve the internal. For example, foreign tech firms might be encouraged to set up R&D in China (bringing knowledge internally), or Belt and Road investments external can secure resources (feeding domestic industry). Xi emphasizes making domestic circulation the mainstay, with external as complement – thus aligning global engagement tightly with national needs, rather than growth for growth’s sake.

Overall, Dual Circulation is a strategic recalibration ensuring that China’s economic engine can keep churning under adverse scenarios. It shows the leadership’s risk-awareness: after witnessing trade wars and pandemics, they are fortifying the country’s economic defenses. In the long run, if successful, it will give China a freer hand in geopolitical contests, less worried about economic blowback. It fits the realism of their approach – preparing the economy for an era of great power rivalry and less benign globalization, essentially future-proofing China’s rise.

State-Owned Enterprises as Strategic Actors

State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) are the often-unseen warriors of China’s economic strategy. While private entrepreneurship has grown in China, the state-owned sector still controls the “commanding heights” of the economy, especially in industries deemed strategic or sensitive. These include energy, telecommunications, banking and finance, steel and heavy industry, construction, transport, and defense manufacturing – sectors that form the backbone of economic and national security. The CCP regards SOEs not just as commercial entities, but as extensions of state power that can be marshaled to serve national strategic goals.