Preface

This third installment of our analytical series continues to unravel the complex tapestry of global power dynamics through the intertwined lenses of geopolitics and geoeconomics. While earlier contributions, notably “Back to Center Stage – China Resurgence,” examined China’s grand strategy in the context of historical continuity and cultural identity, this article shifts to a more technical perspective, dissecting the intricate macroeconomic and structural forces shaping China’s contemporary trajectory.

At the heart of our analysis lies the pivotal concept of “dual circulation,” emblematic of China’s aspiration to strengthen domestic economic resilience while maintaining strategic international engagement. This dual approach underscores a modern geopolitical landscape where economic efficiency, technological prowess, and security concerns are closely interwoven. By meticulously exploring China’s internal structural tensions—ranging from demographic challenges and state-market interactions to intricate global value chain dynamics—we elucidate the profound complexities underlying China’s ambitious strategic objectives.

Recognizing China’s remarkable capacity for rapid adaptation, innovation, and resilience, our assessment carefully balances acknowledgment of these impressive advancements with a clear-eyed examination of enduring challenges. Eschewing premature conclusions, this work highlights the subtle interplay between internal policy decisions and external geopolitical pressures, fostering a nuanced appreciation of China’s evolving economic landscape. Ultimately, this balanced approach aims to deepen understanding of China’s systemic rebalancing efforts and its pivotal role in reshaping global affairs in the coming decade.

1. The Core Paradox: An Unbalanced Engine Despite Decades of Growth

Why does China’s formidable economic engine, even after navigating the significant global disruption of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and achieving decades of unparalleled expansion, remain fundamentally unbalanced in its core structure?

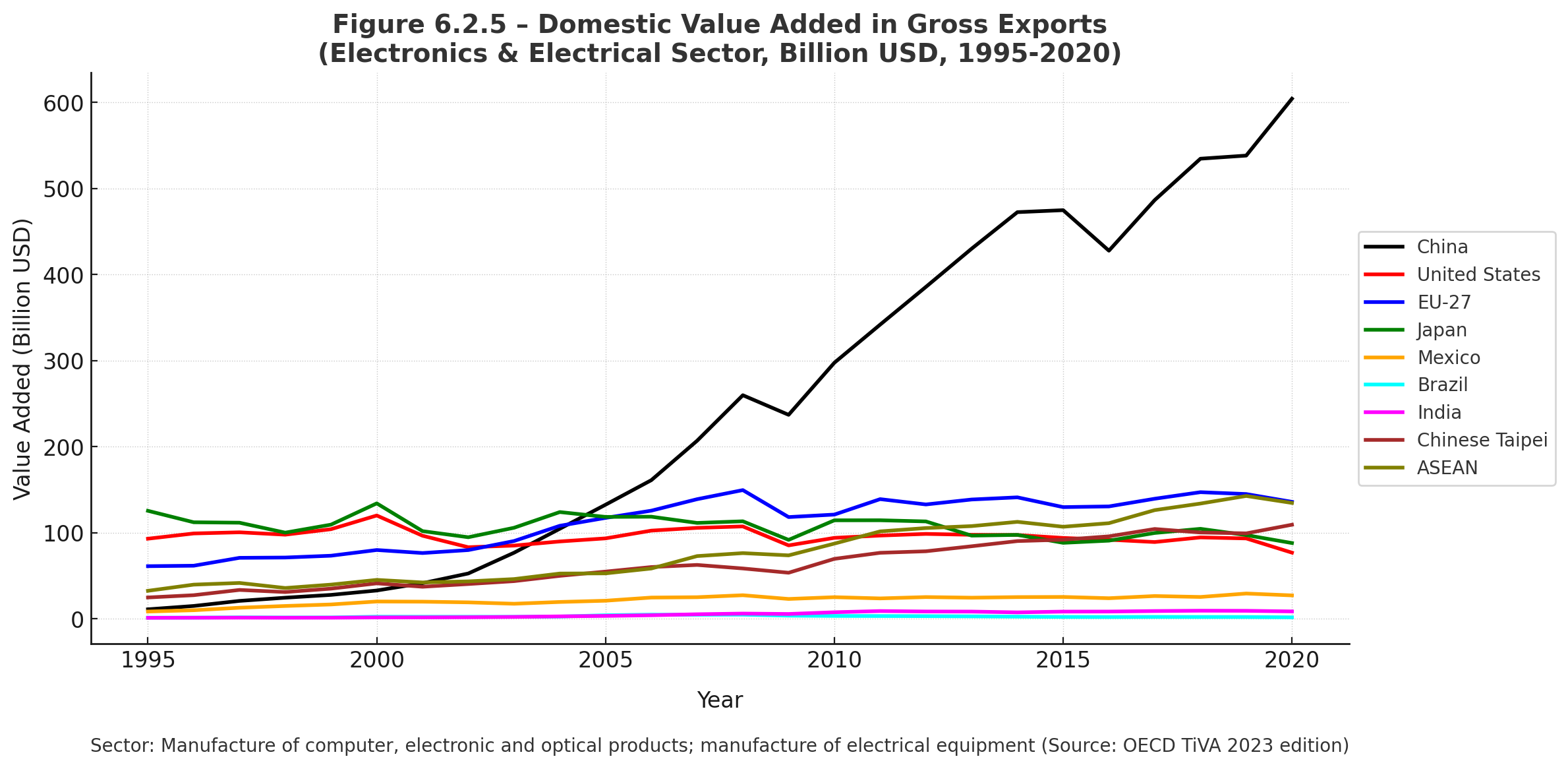

This central question confronts analysts and policymakers alike. Despite recurrent official pronouncements and strategic plans prioritizing a shift towards domestic demand, China’s economic trajectory reveals a persistent and increasingly problematic paradox: its growth continues to lean heavily on exceptionally high rates of investment and the corresponding necessity of exporting surplus national savings, rather than drawing sustainable momentum from robust household consumption typical of maturing economies. This deep-seated structural imbalance, a legacy of its development model, represents a critical vulnerability and the central challenge in its quest for sustainable, high-quality growth within a more contested global environment.

The persistence of this imbalance post-GFC is particularly telling. Macroeconomic data starkly illustrate that household consumption as a share of China’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has shown limited upward momentum, often hovering in the 38-40% range. This figure stands in sharp contrast to international norms and even many peer nations at similar income levels, indicating a structural deviation.

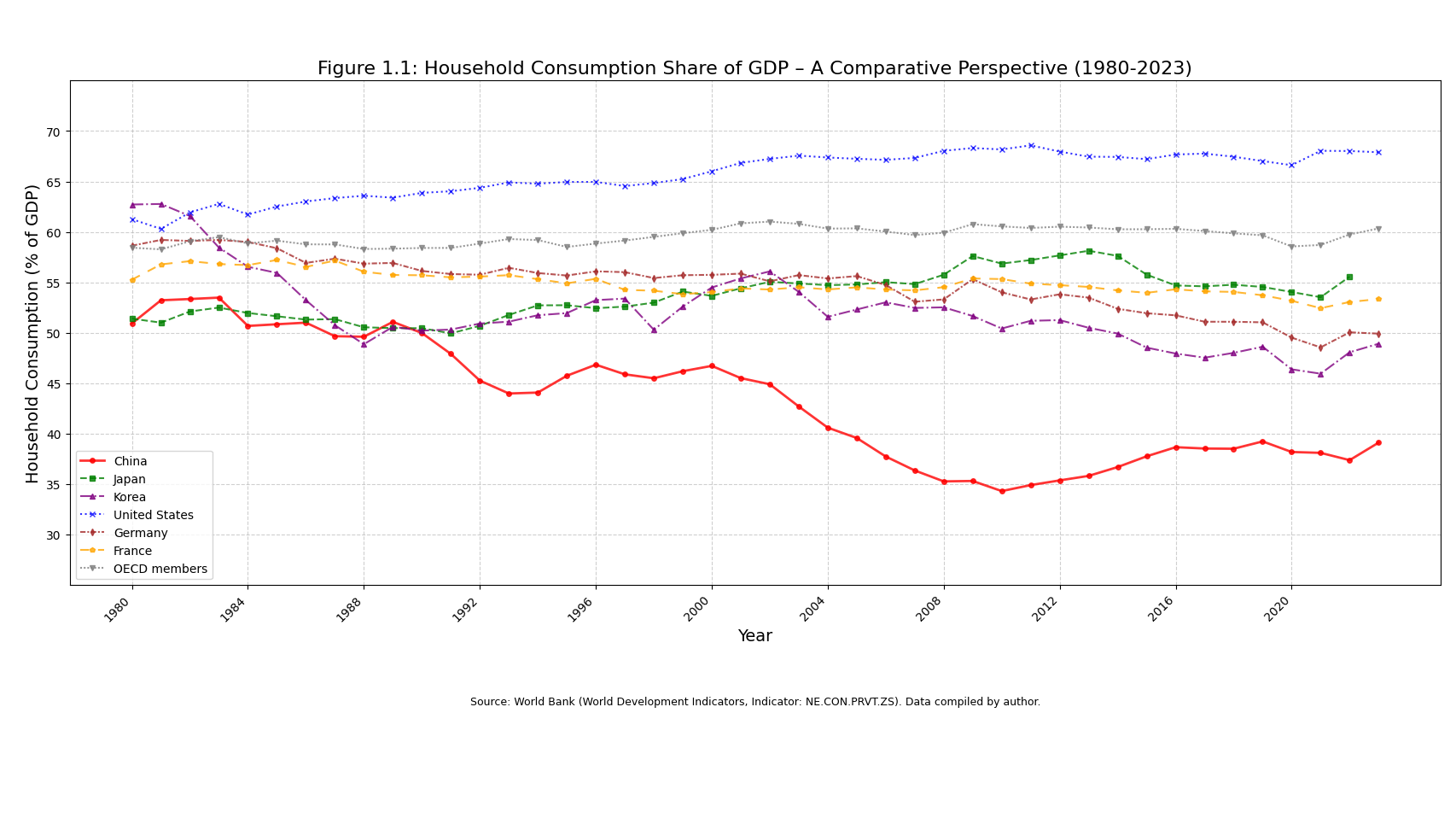

Data Box 1.1: China’s Household Consumption Share – A Persistent Outlier (1980-2023)

A key indicator of China’s structural imbalance is its persistently low share of household consumption in Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This metric not only deviates from developed economies but also from the typical trajectories observed in other rapidly industrializing East Asian economies over an extended period. The analysis now incorporates data from 1980 to 2023, providing a richer historical context.

- China’s Trajectory (1980-2023): Examining the longer time series, China’s household consumption started at higher levels (e.g., often above 50% in the early 1980s) before experiencing a significant decline during the subsequent decades of accelerated investment-led growth, reaching a trough of around 34-35% by 2010. Since then, there has been a slow and partial recovery, with the share hovering in the 38-40% range in the years leading up to and including 2023.

- International Comparisons (1980-2023):

- OECD Average: Developed economies within the OECD typically exhibit household consumption shares consistently around 60% of GDP over this extended period.

- Japan: Over the 1980-2023 period, Japan’s household consumption share, while fluctuating, has generally remained significantly higher than China’s trough, typically in the 55-60% range, reflecting its status as a mature economy.

- South Korea: South Korea’s trajectory since 1980 shows a consumption share that, while experiencing its own shifts during rapid industrialization, has generally been consistently higher than China’s recent levels, often in the 45-55% range.

- Other Comparator Countries (as per user’s dataset): The inclusion of other countries like the USA, Germany, and France over the 1980-2023 period further underscores the differing structural compositions of these economies compared to China.

China’s household consumption trajectory over the extended 1980-2023 period presents a significant deviation from typical economic development paths, where consumption’s share of GDP often stabilizes or rises as national income increases and economies mature. The initial higher share in the early 1980s, followed by a decline during its period of fastest growth and the subsequent limited recovery, underscores the depth of structural factors (such as a low household share of national income, high precautionary savings due to incomplete social safety nets, and the burden of housing costs) that suppress domestic private demand. This quantitatively establishes the “low” consumption base and highlights the scale of the rebalancing challenge China faces in shifting towards a more internally driven and sustainable growth model. The persistence of this low share, despite rising absolute consumption, indicates that the benefits of GDP growth have not proportionally translated into household spending power to the same extent as in many comparator economies.

Concurrently, Gross Capital Formation (investment) has consistently absorbed an extraordinarily high share of national output, remaining above 40% for most of the post-2008 period. Such elevated investment rates, while historically instrumental in building foundational infrastructure and industrial capacity during early stages of development, inherently become less sustainable and efficient as an economy matures, signaling potential resource misallocation and diminishing returns. This theme of declining investment efficiency will be explored further (Chapter 3).

Data Box 1.2: China’s Investment Reliance – An Enduring Outlier

Complementing its low household consumption share, China’s reliance on Gross Capital Formation (GCF), or investment, as a percentage of GDP has been exceptionally high and sustained, particularly since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. This distinguishes China significantly from most major developed and many emerging economies, where investment shares are typically lower or have declined as economies mature.

- China’s Investment Trajectory: China’s GCF as a share of GDP surged dramatically in the 2000s, from around 34% in 2000 to a peak near 47% of GDP around 2009-2011 in the wake of the massive post-GFC stimulus. Since then, it has remained extraordinarily high, generally fluctuating between 42% and 43% of GDP through 2023.

- International Comparisons:

- OECD Average: The average GCF for OECD countries typically ranges between 20% and 25% of GDP.

- United States: The US investment share has generally been lower, often fluctuating between 18% and 23% of GDP.

- Japan: After its high-growth, high-investment phase ended, Japan’s GCF share has typically been in the 23-30% range.

- South Korea: During its rapid industrialization, South Korea saw high investment rates (sometimes exceeding 35%), but these moderated as its economy matured, with recent figures often in the 30-33% range.

China’s sustained high rate of Gross Capital Formation is a defining feature of its economic model. While crucial for early industrialization, maintaining such levels as an economy matures points to an enduring reliance on capital accumulation to drive headline GDP growth, contrasting with more balanced economies. The persistence of this high investment rate, even as returns diminish (discussed in Chapter 3), underscores the structural challenges in shifting towards a more consumption-driven and efficient growth path.

China’s prevailing economic structure—marked by a low household consumption share of national income alongside persistently high investment levels—necessarily translates into an exceptionally high National Savings rate. National Savings, defined as the portion of total GDP not consumed by households or the government, is thus correspondingly large. This high aggregate saving, which includes contributions from households, corporations (notably retained SOE earnings), and the government sector, provides the domestic financial resources fueling the high rate of investment and contributing to external imbalances.

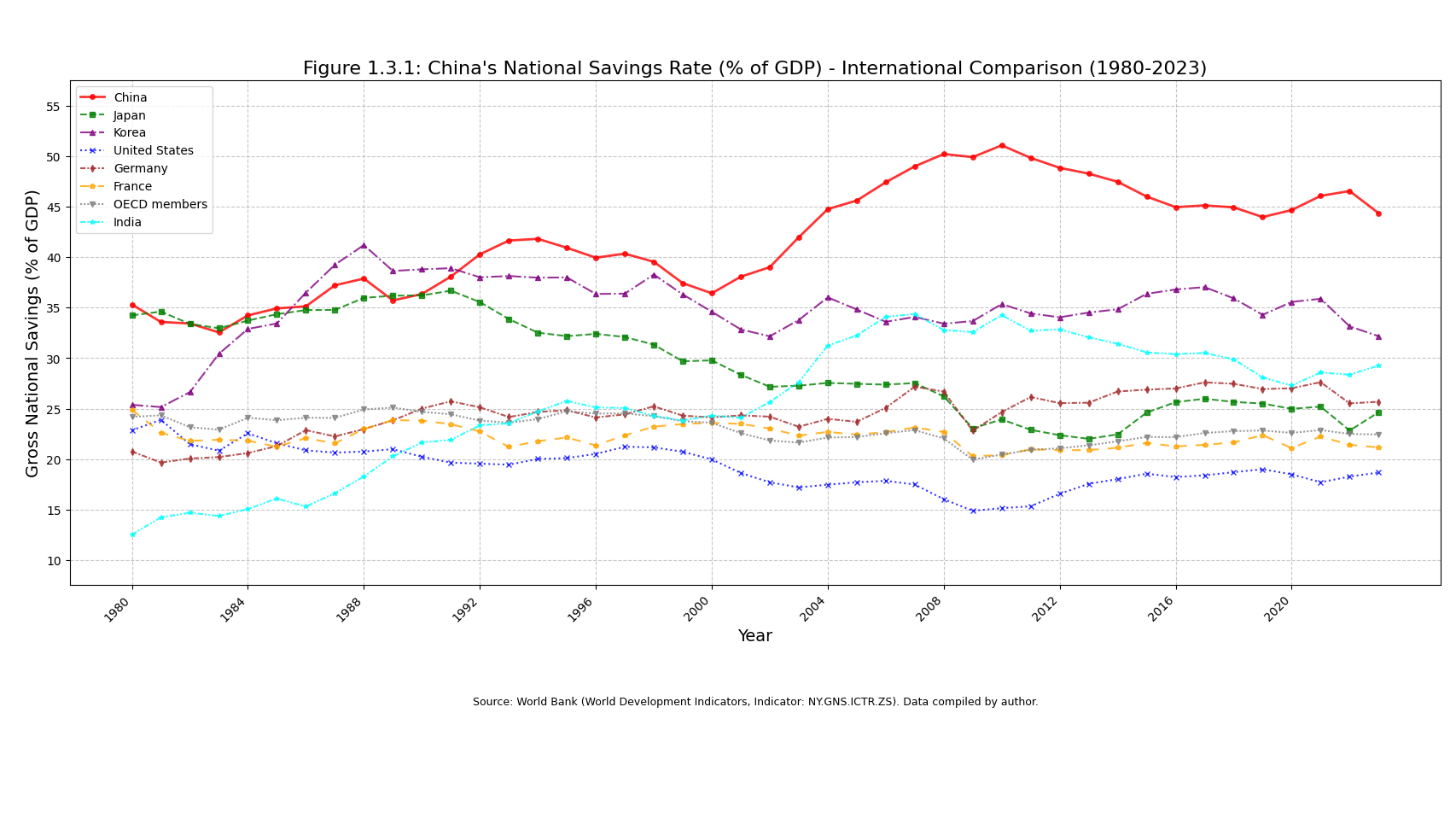

Data Box 1.3: China’s High National Savings Rate – Level, Composition, and International Context

China’s exceptionally high Gross National Savings (GNS) rate is central to its investment-driven growth model and external economic imbalances. Understanding this high savings rate involves examining both its composition within China and its context relative to international benchmarks.

1. Components of National Savings

Gross National Savings (GNS) is total national income (GDP plus net income from abroad) minus household and government consumption. It comprises savings from three main sectors:

- Household Savings: Disposable income minus consumption, influenced by precautionary motives, demographics, housing markets, and credit access.

- Corporate Savings (Non-financial and Financial): Mainly retained earnings, notably from State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs), which often reinvest profits rather than distribute dividends.

- Government Savings: Government revenue minus current consumption expenditure, excluding capital spending.

2. China’s National Savings Rate: International Perspective

Historically, China’s GNS has been remarkably high, increasing from about 35-40% of GDP in the 1980s to over 50% around 2008, then moderating slightly (around 44% in 2023). This consistently surpasses rates in OECD countries and other major economies, highlighting China’s distinctive savings intensity.

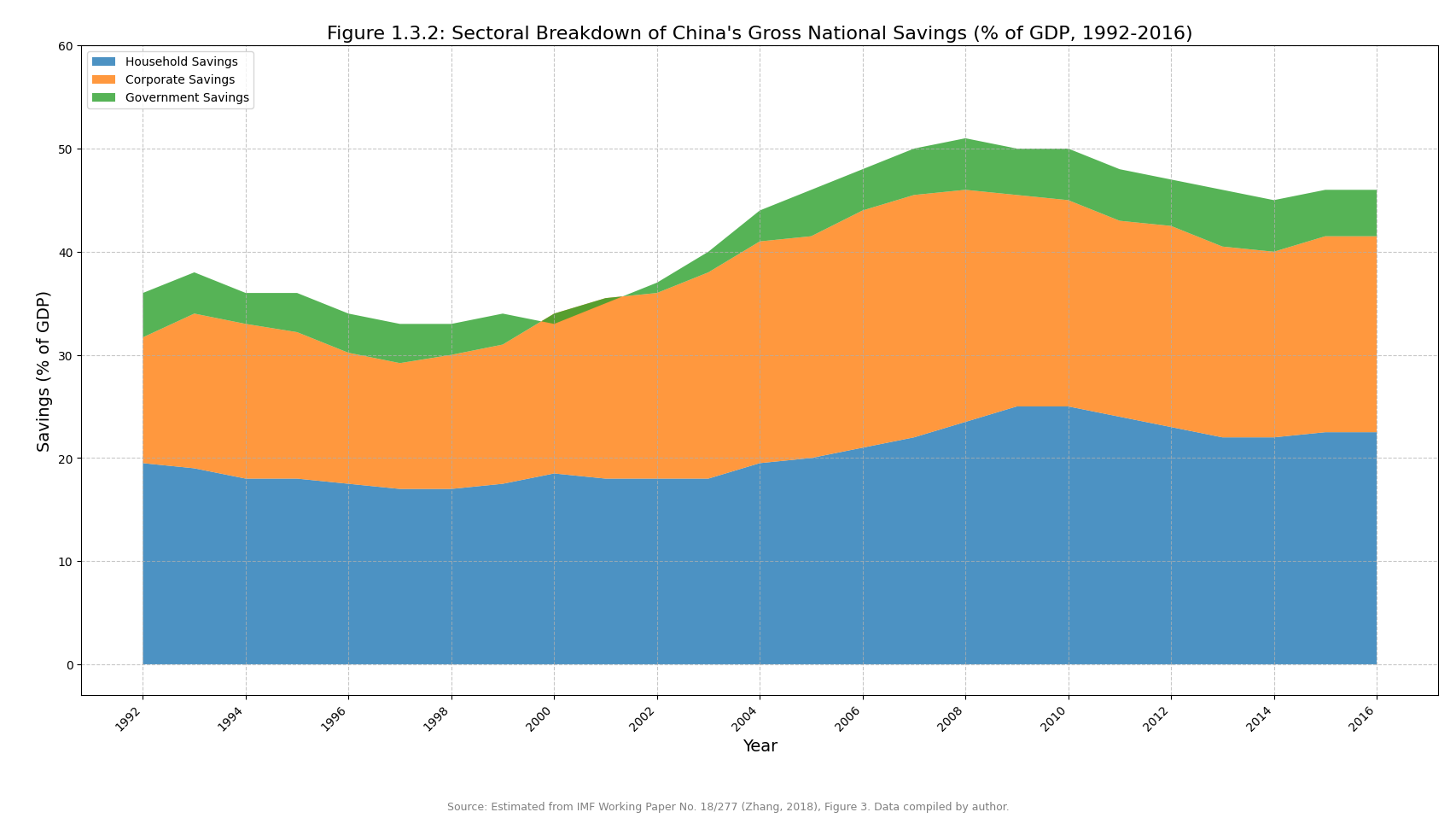

3. Sectoral Contributions within China

From 1992 to 2016, China’s high national savings was driven concurrently by significant contributions from households, corporations, and the government:

- Households: Savings remained robust, rising from 19.5% of GDP in 1992 to a peak around 25% in 2009-2010, settling near 22.5% by 2016. High household savings reflect strong precautionary saving incentives.

- Corporations: Corporate savings became increasingly dominant, climbing from 12.5% of GDP in 1992 to a peak of 23.5% in 2007, moderating to around 19% by 2016. This reflects periods of high profitability, especially among SOEs, and retention-focused policies.

- Government: Government savings, though volatile, typically contributed positively (3-5% of GDP), reflecting revenue growth and fiscal policy emphasizing investment over consumption.

4. China’s Savings in International Context

- Household Savings: China’s household savings (around 23% of GDP mid-2010s) greatly exceed global averages (~8%), highlighting its unique precautionary motives and structural drivers.

- Corporate Savings: Reflecting a global upward trend, China’s corporate saving rate surged significantly, becoming a key national savings component. Though moderating, it remains above the global average.

- Government Savings: Often above global averages, China’s government savings reflect a prioritization of capital investment over current consumption and extensive social transfers, indirectly influencing household saving behavior.

Distinctive Features and Implications:

China’s “all-sector high saving” scenario—where households, corporations, and the government simultaneously contribute significantly—is unique. This arises from the structurally low share of household income in GDP, enabling considerable corporate and government income retention, both sectors exhibiting high saving propensities.

Consequently:

- China’s national savings substantially finance its sustained investment boom.

- Consumption remains suppressed due to income distribution skew and precautionary saving.

- Allocation of substantial corporate and government savings is heavily state-influenced, directed towards strategic sectors and infrastructure, impacting capital allocation efficiency and investment productivity.

Addressing China’s economic rebalancing requires structural shifts: increasing households’ income share, enhancing social safety nets to reduce precautionary savings, and adjusting corporate and government saving-investment behaviors. China’s persistent multi-sectoral high-saving pattern underscores the deep-rooted structural challenges facing its economic transformation.

To understand how this internal configuration of high savings and high investment plays out externally, we turn to the fundamental macroeconomic identity: National Savings (S) minus Domestic Investment (I) equals the Current Account Balance (S - I = CAB).

Definition Box 1.1: The S-I = CAB Identity (The Savings-Investment and Current Account Balance Relationship)

In national income accounting, a country’s total output (Gross Domestic Product, or GDP, denoted as Y) can be expressed as the sum of its expenditures: Household Consumption (C), Government Consumption (G), Investment (I), and Net Exports (Exports (X) minus Imports (M)). Thus, Y = C + G + I + (X - M).

National Savings (S) is defined as the portion of national income (Y) that is not used for current consumption by either households (C) or the government (G). Therefore, S = Y - C - G.

By substituting the expenditure definition of Y into the savings equation, we get:

S = (C + G + I + X - M) - C - G

This simplifies to:

S = I + (X - M)

Rearranging this equation yields the crucial identity:

S - I = X - M

Here, (X - M) represents the Trade Balance (the balance of trade in goods and services). When net income from abroad (such as investment income) and net current transfers are also included, this becomes the Current Account Balance (CAB). For conceptual clarity, the CAB broadly reflects the outcome of the savings-investment balance.

Implication for External Balances:

If a country’s National Savings (S) exceed its Domestic Investment (I), it means the nation saves more than it invests within its own borders (S > I). This condition necessitates that (X – M) must also be positive.

- Excess Savings Flow Abroad: The surplus domestic savings (

S - I) are channeled internationally, making the country a net lender to, or net investor in, the rest of the world. This outflow of financial capital signifies the country acquiring foreign assets. - Mirrored in Trade: For this net financial outflow to occur, the country must, on balance, be exporting more goods and services than it is importing. Its exports (X) must exceed its imports (M), resulting in a trade surplus, which is the primary component of a current account surplus. In essence, a current account surplus indicates a country is a net exporter of capital, which is only possible if it also exports more goods and services than it imports. The excess of savings over domestic investment provides the financial resources for this net export of capital, mirrored by a net export of goods and services. Conversely, if I > S, the country must import capital, reflected in a current account deficit (M > X).

Given that China’s aggregate national savings persistently exceed even its substantial domestic investment requirements (S > I), the nation must export this surplus capital. This manifests as a persistent Current Account Surplus. While the surplus’s relative size (as % of GDP) declined from its pre-GFC peak (near 10%) to typically fluctuate between 1-3% post-2010 (with notable post-COVID spikes), its stubborn persistence, particularly its often large absolute value (running into hundreds of billions of USD annually), signals unequivocally that the core internal rebalancing towards consumption has fundamentally stalled.

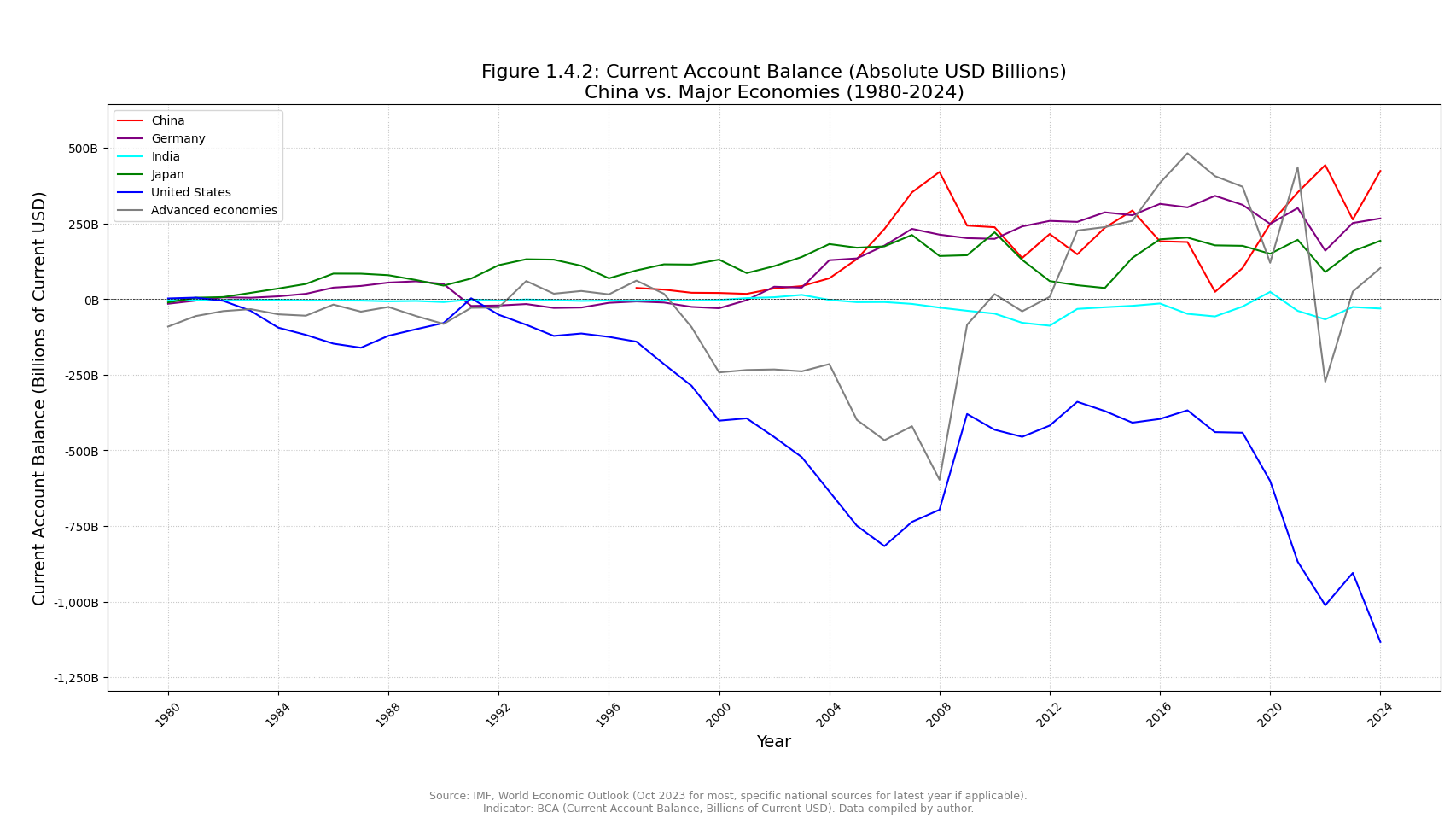

Data Box 1.4: China’s Current Account Balance – Relative vs. Absolute Significance

The Current Account Balance (CAB) reflects a nation’s economic interaction with the global economy through trade, income flows, and transfers. Analyzing China’s CAB as both a percentage of GDP and in absolute dollar terms provides complementary insights.

1. Current Account Balance (% of GDP)

China’s CAB peaked around 10% of GDP in 2007 and subsequently moderated to around 1-2.5% for much of the 2010s, with occasional increases such as post-COVID. Even at lower percentages, this persistent surplus highlights China’s enduring domestic savings-investment imbalance.

Comparison with Germany and Japan:

- Germany: Typically records higher CAB surpluses (as % GDP) than China, driven by export competitiveness, integration into EU/global value chains, and structural advantages from Euro membership. Germany’s surplus reflects high national savings combined with comparatively lower domestic investment.

- Japan: Maintains consistent surpluses primarily due to significant net income from decades of foreign investments. Japan’s competitive export sectors, demographic factors, and mature industrial structure support persistent surpluses.

China’s Distinction: Unlike Germany and Japan, China’s surplus is rooted in suppressed household consumption due to low household income shares, precautionary savings driven by weaker social safety nets, and state-driven investment funded by substantial corporate (especially SOEs) and government savings. Thus, China’s surplus directly indicates deep internal imbalances.

Other Global Contexts:

- United States: Consistently runs large deficits as a global consumer and capital importer.

- India: Typically shows deficits due to investment needs exceeding domestic savings.

China’s CAB persistence underscores its incomplete shift toward consumption-driven growth, highlighting structural economic challenges rather than surplus scale alone.

2. Current Account Balance (Absolute U.S. Dollar Terms)

Given its massive economy, China’s absolute CAB surplus regularly ranks among the world’s largest. Even modest percentages of China’s GDP yield substantial absolute surpluses ($180-$360 billion annually for 1-2% of an $18 trillion economy), significantly impacting global financial markets.

Global Impact: China’s large absolute surplus positions it as a leading global capital exporter, significantly shaping worldwide investment flows and financing deficits elsewhere, notably in the U.S.

Comparison with Germany and Japan: While Germany and Japan also record substantial absolute surpluses, reflecting their economic size and export strengths, China’s surplus frequently matches or exceeds theirs, emphasizing China’s vast production capacity and continued reliance on external markets.

Qualitative Differences Behind Similar Numbers:

Though Germany, Japan, and China all exhibit significant surpluses, their underlying causes vary substantially:

- Germany and Japan: Mature, high-income economies with strong domestic consumption, advanced social welfare systems, specialized export sectors, and robust international investment positions. Their surpluses reflect mature industrial competitiveness, favorable macroeconomic conditions (Eurozone dynamics for Germany), and accumulated foreign investment income (Japan).

- China: Persistent surplus stems directly from structural imbalances—low household income shares, high precautionary savings, insufficient social safety nets, and investment-heavy, state-driven economic growth. China’s external surplus is thus symptomatic of deep internal economic imbalances.

Recognizing these qualitative distinctions is crucial. China’s challenge in rebalancing is unique, necessitating addressing specific internal structural and policy issues rather than merely focusing on the scale of its surplus.

The Chinese economy thus remains structurally geared to produce significantly more than it consumes domestically. This foundational paradox generates a complex nexus of internal economic risks—such as diminishing returns on investment, asset bubbles, and inefficient capital allocation (detailed in subsequent Chapters)—and significant external friction within the global trade and financial system (explored in Chapter 6). Understanding this core imbalance is the essential starting point for dissecting the multifaceted challenges of China’s ongoing rebalancing imperative, an undertaking whose success is far from guaranteed and whose trajectory is fraught with the tensions between economic logic and entrenched political-economic structures.

2. The Household Squeeze: Structural Barriers to Consumption

What structural barriers (income share, safety nets, housing costs) prevent Chinese households from spending more, forcing high savings even as the nation gets richer?

The core paradox of China’s unbalanced economic engine, as established in chapter 1, is centrally characterized by persistently low household consumption relative to the nation’s overall output. While high national savings fuel extensive investment, the comparatively muted role of household spending as a primary growth driver points to deep-seated structural impediments. This chapter dissects these barriers, revealing a “household squeeze” where Chinese families, despite rising absolute incomes, are systematically constrained in their capacity and willingness to consume. This is not merely a cultural inclination towards thrift but a rational response to a political economy that has historically limited their share of national income, provided an inadequate social safety net, and channeled significant household resources towards an often burdensome housing market. Understanding these interconnected pressures is vital to grasping why rebalancing towards a more internally driven, consumption-led growth model has proven so profoundly challenging for Beijing.

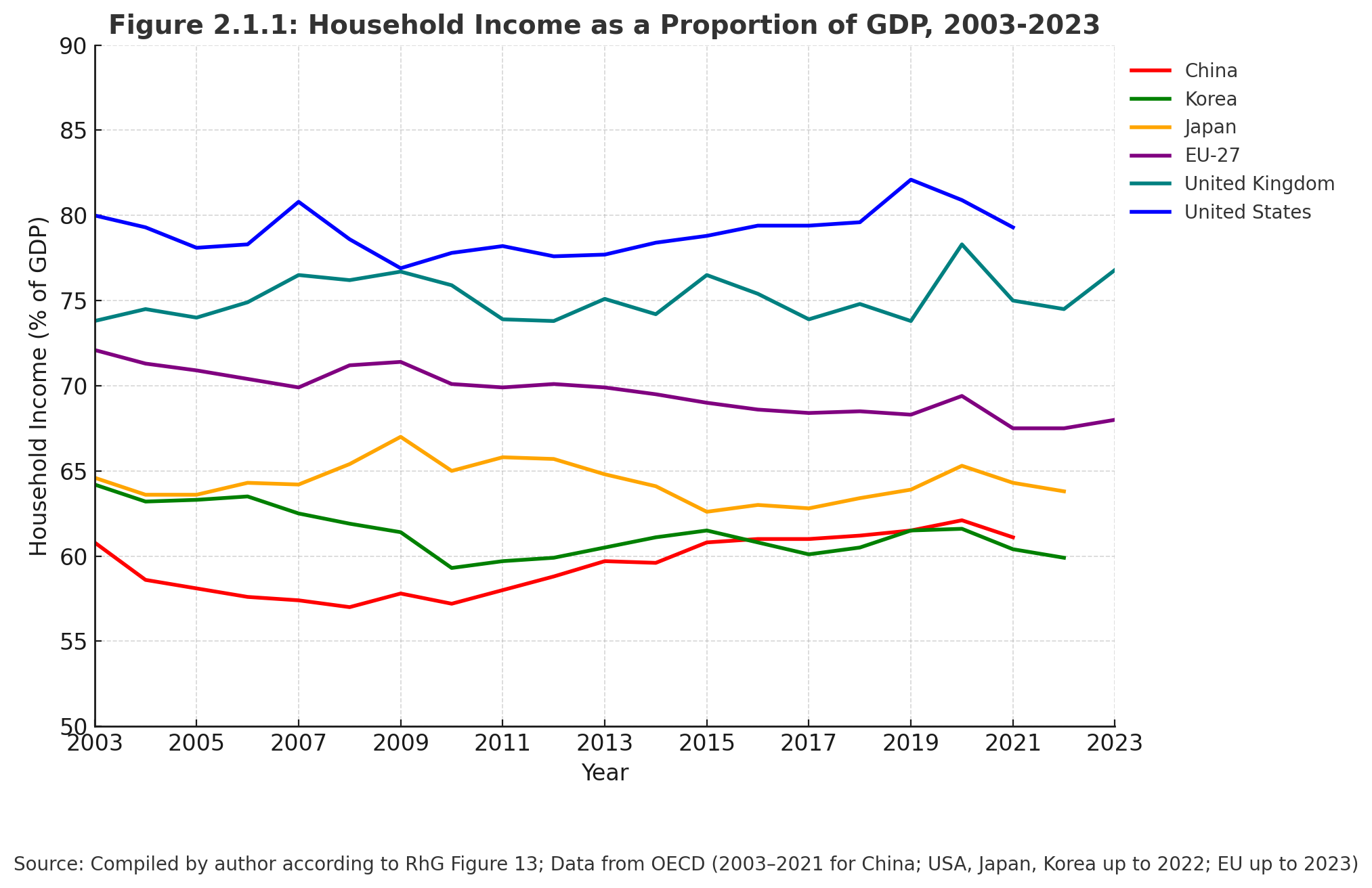

Foremost among these constraints is the structurally low share of national income accruing to households. While many economies see household income and consumption shares rise or stabilize as they mature and transition towards service-based structures, China’s trajectory has been notably divergent. After an initial period where household income represented a larger portion of the economy, this share experienced a relative decline during the decades of hyper-growth fueled by investment and exports. Even with subsequent recovery, the portion of GDP ending up in household pockets remains significantly below levels observed in most developed economies and, critically, below what historical precedents from other East Asian economies at similar developmental stages would suggest. This persistent suppression of the household income share fundamentally limits the aggregate purchasing power available to drive consumption.

Several mechanisms contribute to this suppressed income share. For extended periods, policies such as financial repression—whereby interest rates on household bank deposits were deliberately kept low, often below inflation—effectively transferred wealth from savers (primarily households) to borrowers (often state-owned enterprises and government entities funding investment). This directly curtailed household income derived from capital. Furthermore, the profit distribution patterns of a state-dominated corporate sector, particularly State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs), tend to favor reinvestment or remittances to the state over substantial dividend payouts to a broader shareholder base or significantly higher wage growth relative to productivity gains. While the detailed role of SOEs will be explored in Chapter 4, their impact on channeling national income away from households is a critical factor here. The sheer scale and internal diversity of China, with significant regional income disparities between affluent coastal areas and lagging inland provinces, adds another layer of complexity, though the national aggregate figure remains stubbornly low, underscoring a systemic issue.

Data Box 2.1: China’s Household Income Share of GDP – Analysis, Comparisons, and Regional Nuances

The share of household income within a nation’s GDP significantly influences economic distribution and domestic consumption capacity. China’s trajectory highlights intricate dynamics shaped by historical developments, structural policies, and regional disparities.

1. National Trends and Comparative International Analysis

Over the past two decades, China’s household income share gradually rose from approximately 57-58% in the mid-2000s to about 60-61% by 2023. This recent upward trend represents a partial recovery following a sharp decline during China’s rapid industrialization and investment-intensive growth period in the 1990s and early 2000s, where households’ income shares were notably suppressed.

Detailed Comparative Context:

- Developed Western Economies: Despite improvements, China’s household income share remains significantly lower compared to advanced Western economies such as the United States (78-82%) and the European Union average (68-72%). This gap underscores fundamental structural differences, including more developed social safety nets, higher wage levels, and a more consumption-driven growth model prevalent in Western economies.

- East Asian Comparative Dynamics:

- Japan: Maintains a consistently higher household income share (63-67%), supported by established income distribution mechanisms, a mature welfare system, and corporate structures such as the Keiretsu, which, despite their interconnected nature, allocate substantial profits directly into household incomes.

- South Korea: Historically higher household income shares relative to China have recently converged around the 60-61% mark. Yet, critical structural nuances persist. South Korea’s Chaebols typically distribute a larger proportion of profits through direct wages, dividends, and employee benefits, fostering stable household income streams. By contrast, China’s State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) retain a significant portion of profits for reinvestment or state-directed expenditures, limiting direct household distributions and necessitating compensatory mechanisms like government transfers to sustain household income levels.

Structural and Institutional Considerations:

Beyond corporate profit distribution mechanisms, differences in state intervention policies, welfare provisions, and financial regulatory frameworks further distinguish China’s income dynamics from those of Japan and South Korea. China’s financial repression, limited direct corporate profit sharing, and historically underdeveloped social safety nets reinforce precautionary saving behavior and household income suppression, creating deeper economic fragility compared to its East Asian counterparts.

Rebalancing China’s Economic Model:

While the increase in China’s household income share is encouraging, its effectiveness and sustainability require careful consideration:

- Pace of Transition: The incremental nature of household income share increases raises concerns about the adequacy and timeliness relative to China’s moderating GDP growth.

- Sustainability of Drivers: Reliance on temporary fiscal measures or superficial policy interventions, rather than foundational reforms in income distribution (such as wage growth and profit distribution policies), may limit long-term impact.

- Persistent Structural Constraints: Factors such as SOE profit retention practices, Hukou system restrictions affecting migrant incomes, and the perceived inadequacy of social safety nets continue to constrain substantial improvements in household consumption capacity.

2. Internal Regional and Social Income Diversity

National averages obscure substantial internal variations, essential for a comprehensive understanding of China’s economic landscape:

- Regional Inequality: Stark disparities remain pronounced. In 2023, per capita disposable income in prosperous coastal areas such as Shanghai (RMB 84,834) and Beijing (RMB 81,752) vastly exceeded less-developed western regions like Gansu (RMB 25,011) and northeastern provinces like Heilongjiang (RMB 29,694). These differences highlight persistent uneven development and structural policy biases.

- Urban-Rural Divide: Within each province, urban households consistently demonstrate significantly higher income levels compared to rural areas, driven by varied economic opportunities, industrial structures, infrastructure availability, and resource accessibility.

- Historical and Structural Drivers: These regional and urban-rural disparities originate from coastal-centric development policies, varied industrial compositions, uneven impacts of urbanization, and Hukou system restrictions that limit labor mobility and urban welfare access.

Policy and Structural Reform Implications:

To effectively enhance China’s overall household consumption and achieve the policy goal of “Common Prosperity,” targeted interventions are crucial. Policymakers must address deep-rooted regional inequalities, promote income redistribution, strengthen social safety nets, and reform corporate governance, particularly within SOEs. Without addressing these underlying disparities and structural impediments, China’s transition toward a sustainable, consumption-driven economy will remain incomplete.

Conclusion:

China’s improving household income share is promising but must be contextualized within historical suppression, ongoing structural challenges, and deep regional disparities. A genuinely balanced economic transition necessitates comprehensive structural reforms and nuanced policy interventions tailored to China’s unique socio-economic landscape.

Definition Box 2.1: Financial Repression – Mechanisms and Impacts in China

What is Financial Repression?

Financial repression describes government policies that artificially distort financial markets to direct funds to state-favored sectors or objectives at below-market costs. These policies intervene in market-determined interest rates, exchange rates, and capital allocation, typically disadvantaging household savers and private enterprises outside state priorities.

Key Mechanisms in China’s Context:

Historically, China extensively employed financial repression to sustain its investment-driven and export-oriented economic model, primarily from the 1980s through the mid-2010s. Key methods included:

- Interest Rate Controls: The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) set deposit interest rates below market-clearing levels and often below inflation, resulting in prolonged negative real returns for households.

- Directed Credit and State-Dominated Banking: The largely state-owned banking system preferentially allocated credit to State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs), infrastructure, and strategic industries at subsidized rates.

- Capital Controls: Restrictions on international capital flows limited households’ investment options, reinforcing low domestic returns on savings and insulating the domestic financial market.

- High Reserve Requirements: Imposed high reserve requirements constrained banks’ lending capacity, ensuring a stable, low-cost funding source for the government and controlled credit growth.

Quantitative Impacts and Evidence:

Extensive research quantifies the effects of these policies in China:

- Implicit Tax on Households: Studies by economists such as Lardy (2008, 2012) estimated the implicit tax from negative real interest rates to be several percentage points of GDP annually during peak periods, effectively transferring wealth from households to state-linked sectors and constraining disposable household income.

- Suppressed Household Income and Consumption: Low returns on savings limited household income growth and contributed to the persistently low household income share of GDP, dampening household consumption’s role in economic growth.

- Investment Misallocation: Cheap capital availability fueled high investment rates but often resulted in misallocation. State-linked entities accessed abundant, subsidized credit even when returns on investments were lower compared to constrained private enterprises, potentially reducing overall productivity and efficiency.

- Current Account Imbalances: Financial repression reinforced the structural gap between savings and investment, sustaining large current account surpluses by suppressing domestic consumption and promoting high savings rates.

Legacy and Current Relevance:

Although China has significantly liberalized financial markets since the mid-2010s (e.g., interest rate liberalization and capital market development), the historical impacts of decades-long financial repression persist. Residual biases favoring SOEs in credit allocation and underdeveloped financial markets still influence savings behaviors, consumption patterns, and resource allocation. Addressing these entrenched legacies remains central to China’s ongoing economic rebalancing toward sustainable, consumption-driven growth.

Compounding the impact of a constrained income share is the pervasive necessity for high precautionary savings, driven by deep-seated anxieties about the adequacy of China’s social safety net. While China has achieved remarkable progress in expanding basic coverage for pensions, healthcare, and unemployment insurance, particularly since the early 2000s, the perceived quality, comprehensiveness, and generosity of these systems often fall short of providing genuine financial security for many households. Public social expenditure as a percentage of GDP, though rising, still lags behind that of many OECD countries. This compels households to accumulate substantial private savings as a buffer against future uncertainties and critical life-cycle expenditures:

- Healthcare: Despite near-universal basic health insurance, significant out-of-pocket expenses due to coverage gaps, reimbursement caps for serious illnesses, and co-payments mean that a major health event can be financially catastrophic for many families. This compels significant precautionary savings.

- Education: The high costs associated with ensuring children receive a quality education, from primary through tertiary levels (including historically significant spending on supplementary tutoring, even if recently curtailed by policy), represent a major financial planning burden.

- Pensions: While pension coverage has broadened, concerns about the adequacy of future benefits, especially for those outside the formal urban employment system or in a context of rapid aging, motivate individuals to save substantially for their own retirement.

This environment of pervasive uncertainty rationalizes high household saving rates. Faced with these potential future burdens and an incomplete public shield, families across various income strata curtail current consumption to build a financial buffer, directly dampening aggregate domestic demand.

Data Box 2.2: China’s High Household Savings – International Context and Internal Variations

China’s persistently high household savings rate significantly constrains domestic consumption and shapes its overall economic structure. This phenomenon is not simply cultural but rather reflects rational responses to structural and institutional conditions, notably perceived weaknesses in social safety nets.

1. China’s Household Savings: An International Outlier

Over the past two decades, China’s household net savings rate (as a percentage of net disposable income) has consistently ranked among the world’s highest, typically ranging between 30-35+%. This rate starkly contrasts with averages in OECD countries (generally 5-10%) and advanced economies such as the United States, Germany, Japan, and South Korea. This substantial gap underscores the unique structural conditions driving Chinese household saving behaviors.

2. Internal Variations in Household Savings Rates

Aggregate national figures mask significant disparities across different societal groups in China, shaped primarily by income level, Hukou status, and employment sector:

| Comparison Group | Savings Rate (%) | Year | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urban vs. Rural | |||

| Urban | ~38% | 2020 | IMF Analysis |

| Rural | ~20% | 2020 | IMF Analysis |

| Hukou Status (Urban) | |||

| Migrants | 48.5% | 2010-2013-2017 | Tan et al. (2021) |

| Locals | 39.9% | 2010-2013 | Tan et al. (2021) |

| Income Level | |||

| Low-Income | ~32% | 2020 | IMF Analysis |

| Middle-Income | ~36% | 2020 | IMF Analysis |

| High-Income | ~39% | 2020 | IMF Analysis |

| Public vs. Non-Public Employees | |||

| Public Sector Employees | Higher by 3-8 pp | – | Xu, Can; Steiner, Andreas (2022) |

These internal disparities highlight that vulnerability, income insecurity, and differential access to public services significantly influence savings behaviors. Migrants, lacking stable urban social protections due to Hukou restrictions, save at notably higher rates, driven by precautionary motives and future uncertainties.

3. Social Safety Nets and Precautionary Savings

The primary factor underlying China’s high household savings rate is strong precautionary saving behavior—households setting aside significant resources to mitigate risks related to healthcare, retirement, and education due to perceived inadequacies in public welfare systems:

- Healthcare: Basic health insurance covers most people, but gaps and low reimbursement rates result in high out-of-pocket costs and potential catastrophic health expenses. Migrants often face additional access barriers in urban areas.

- Pensions: China’s fragmented pension system, characterized by varying and often modest benefits, fosters uncertainty about retirement income adequacy, prompting individuals to accumulate substantial personal savings.

- Education: While public education is broadly available, families incur significant supplementary educational expenses, including tutoring and higher education preparation, fueling further saving needs.

Bottom Line :

The exceptionally high household savings rate in China, coupled with pronounced internal variations, highlights the profound impact of structural factors and social policy limitations. Strengthening social safety nets and addressing access inequalities can significantly reduce excessive precautionary saving, thereby enhancing household consumption and contributing to China’s broader economic rebalancing.

Finally, the extraordinary burden of housing costs and the associated surge in household debt acts as a third major constraint on discretionary household spending. Driven by a confluence of factors including rapid urbanization, housing’s role as a primary investment vehicle in an environment of limited alternatives, government land policies, and strong cultural preferences for homeownership, property prices in major Chinese cities have reached levels that are exceptionally high relative to average incomes. To achieve the deeply ingrained aspiration of owning a home, households have been forced to dedicate vast resources towards accumulating down payments—often requiring financial support pooled across multiple generations—and subsequently servicing substantial mortgage debt. Consequently, household debt as a percentage of GDP, primarily driven by mortgages, has surged dramatically from below 20% in 2008 to over 60% by the early 2020s. While this credit expansion has facilitated property acquisition, the resulting debt service obligations consume a significant portion of monthly household income, directly limiting funds available for other forms of consumption. The recent downturn in the property market, while aiming to correct speculative excesses, may also negatively impact consumer confidence through wealth effects, further tempering spending.

Data Box 2.3: China’s Housing Affordability Crisis and Household Debt – The “Double Bind”

China’s persistently high household savings and constrained domestic consumption are significantly intensified by the “double bind” of extreme housing costs and mortgage-heavy household debt, limiting disposable income far beyond what aggregate debt-to-GDP ratios might imply.

1. Extreme Housing Price-to-Income Ratios (P/I)

The Price-to-Income (P/I) ratio measures housing affordability by indicating how many years of median household income are required to buy a median-priced home. Chinese Tier-1 cities consistently rank among the world’s least affordable, severely impacting household financial stability and consumption capacity:

| City | Country | P/I Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Beijing (2015) | China | 18.1 |

| Beijing (2025) | China | 37.4 |

| Shanghai | China | 38.0 |

| Shenzhen | China | 27.5 |

| Hong Kong | China (SAR) | 28.6 |

| London | UK | 20.3 |

| New York | USA | 15.3 |

| Tokyo | Japan | 14.7 |

Source: Numbeo 2025, RIETI.

China’s extreme ratios (typically 25–40 years of income) significantly surpass those of other expensive global cities (15–20 years), driven by intense demand, cultural emphasis on homeownership, and multi-generational wealth pooling to afford initial down payments.

2. Rapid Household Debt Accumulation and Mortgage Dominance

China’s household debt-to-GDP ratio escalated sharply from approximately 18% in 2008 to over 63% by 2023. Although lower than some developed countries (e.g., the US), China’s debt composition imposes significantly higher monthly financial burdens on households:

- Mortgage Concentration: Mortgages are the single largest component (≈ 60 percent) of Chinese household debt. The remaining 40 percent consists of high-cost consumer credit, auto loans, and small student‐loan balances. By contrast, many advanced economies have even higher mortgage shares (≈ 65 – 80 percent), but their non‐mortgage debt (student, auto, credit‐card) typically carries lower rates or longer tenors, softening monthly payment pressures.

- Consumer Credit Expansion: Short-term consumer credit via digital platforms (Alipay, WeChat Pay) accounts for roughly 10–15% of household debt. However, these loans are secondary compared to the substantial mortgage obligations households carry.

3. Why China’s Housing Debt Burden Is Higher Despite Lower Debt-to-GDP

China’s lower overall debt-to-GDP ratio masks the real financial pressures households face:

| Metric (2023) | China | United States |

|---|---|---|

| Mortgage share of household debt | ≈60% | ≈70% |

| Average mortgage interest rates | 3.5–4.5+% | 2.7–4.5% (pre-2022) |

| Median P/I ratio (largest cities) | 25–40 | 15–20 |

| Mortgage payment as % household income | 40–60% | 25–30% |

High interest rates, substantial down payments (typically 20%), and extreme housing prices severely constrain monthly disposable income, placing significantly heavier cash-flow pressures on Chinese households compared to their counterparts in developed economies, even where aggregate debt-to-GDP ratios appear higher.

4. Economic and Policy Implications

- Consumption Constraint: High mortgage repayments and upfront housing costs limit discretionary spending, significantly impeding China’s shift toward domestic consumption-led growth.

- Financial Vulnerability: Elevated mortgage burdens expose households to significant risks from economic shocks, interest rate increases, or housing market downturns, potentially impacting broader economic stability.

- Policy Imperatives: Sustainable economic rebalancing requires policy measures addressing housing affordability, including land-use reforms, taxation adjustments, diversified household asset options, and improved social welfare systems to mitigate excessive reliance on real estate as the primary asset.

In concert, these three structural forces—a limited household share of national income that deviates from typical development trajectories, systemic incentives for high precautionary saving arising from gaps in social welfare provision, and the immense financial weight of the housing market—create a powerful and persistent squeeze on household consumption potential. Addressing this “consumption conundrum” is not a matter of simple stimulus measures; it necessitates deep, politically sensitive reforms targeting income distribution, the architecture of the social safety net, and the fundamental role of property in the economy. These are reforms that directly confront entrenched interests and the established mechanisms of China’s state-led development model, testing the leadership’s resolve and capacity to genuinely re-engineer the drivers of the nation’s growth. The difficulty in overcoming these barriers directly contributes to the imbalances detailed in Chapter 1 and sets the stage for the debt-related challenges explored in Chapter 3.

3. The Debt Drag: Stimulus Legacy, Diminishing Returns, and Constrained Rebalancing

How did the post-2008 stimulus legacy create a debt overhang (LGFV, property) that now yields diminishing returns and constrains policies needed for rebalancing?

The constraints on China’s household consumption, detailed in the previous chapter, represent one critical facet of its rebalancing challenge. However, the other side of the economic ledger—the investment-driven growth model—has simultaneously generated its own formidable set of structural impediments. China’s decisive response to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) successfully averted a sharp economic downturn through a massive credit-fueled stimulus. Yet, this intervention, while lauded at the time for its efficacy in supporting global growth, sowed the seeds of a colossal debt overhang. This legacy of debt, concentrated particularly in local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) and the sprawling property sector, now acts as a significant drag on the economy. It is characterized by diminishing returns on new investment and severely constrains the policy space Beijing needs to navigate towards a more sustainable, consumption-driven growth model. Understanding the genesis, scale, and multifaceted consequences of this debt burden is crucial to appreciating the depth of China’s rebalancing predicament.

The sheer scale of China’s debt accumulation in the post-GFC era is striking. Prior to 2008, China’s total non-financial debt (encompassing government, corporate, and household sectors) was at a relatively manageable level, estimated to be around 140-160% of GDP. The ¥4 trillion stimulus package unleashed in 2008-2009, predominantly channeled through bank lending and off-balance-sheet entities, triggered an unprecedented credit expansion. By the late 2010s, total non-financial debt had surged past 250% of GDP, and by end-2023/early 2024, prominent estimates placed this ratio at 300%. This rapid leveraging, far outpacing nominal GDP growth over the same period, has brought China’s overall debt burden to levels comparable with, or even surpassing, many highly financialized advanced economies. However, this has occurred without China possessing the same depth of capital markets, robust institutional frameworks for debt resolution, or the established financial shock absorbers typically found in those economies.

Data Box 3.1: China’s Debt Surge Post-2008: Scale, Composition, and Economic Implications

China’s rapid buildup of debt following the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) significantly reshaped its economic landscape, presenting major risks and policy challenges. This box outlines the scale, composition, and broader economic consequences of China’s debt surge.

1. Rapid Debt Accumulation Post-2008

Before the GFC, China’s total non-financial sector (NFS) debt—covering government, corporate, and household sectors—was around 140–160% of GDP. Triggered by the ¥4 trillion stimulus in 2008–09, debt quickly escalated, reaching over 250% by the late 2010s and approaching 300% of GDP by end-2024. This puts China in the same league as many highly indebted advanced economies, despite lacking comparable institutional safeguards or market depth.

2. Who Holds China’s Debt?

By end-2024, China’s NFS debt was structured as follows:

| Sector | % of GDP (2024) | Share of total debt |

|---|---|---|

| Corporate Sector (NFC) | ≈140% | ≈50 ppts |

| – LGFVs | 42–46% | ≈⅓ of corporate debt |

| – SOEs | 45–53% | ≈⅓ of corporate debt |

| General Government (on-budget) | ≈85% | ≈30 ppts |

| Households | ≈60% | ≈20 ppts |

Source: BIS data.

3. Understanding LGFVs and Their Role

Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs) are special-purpose companies created by local authorities to fund infrastructure and development projects without appearing on official government balance sheets. They emerged due to restrictions on local-government bond issuance, borrowing heavily from banks, bond markets, and shadow credit channels. By 2023, LGFV liabilities totaled roughly ¥55–60 trillion (~40-45% of GDP), accounting for about one-third of corporate debt. The IMF’s augmented metrics reclassify LGFV debt as public sector, raising China’s true public debt significantly.

4. Structural Economic Implications

- State-Directed Dominance: Approximately two-thirds of corporate debt is tied to state entities (LGFVs and SOEs), indicating a government-driven investment focus.

- Declining Investment Efficiency: Each additional yuan of debt now generates progressively less economic growth, shown by China’s sharply rising Incremental Capital-Output Ratio (ICOR).

- Limited Policy Flexibility: Heavy obligations from LGFV and SOE debts consume fiscal and banking resources, reducing available funds for social spending and consumer-focused stimulus.

Household Debt Trends Post-2020: Post-2020, household debt relative to GDP stabilized and even declined slightly due to property-market weakness, accelerated debt repayment, and increased consumer caution. This reinforces that China’s post-2008 debt surge primarily reflects state-directed, infrastructure-focused borrowing rather than household leverage.

5. Key Takeaways for Economic Rebalancing

China’s post-2008 debt growth—particularly via opaque LGFVs and SOEs—poses major barriers to shifting towards a consumption-driven economy. Effective rebalancing requires:

- Significant restructuring of LGFV debt;

- Reforming land-financing mechanisms;

- Strengthening SOE financial discipline;

- Enhancing transparency and market-based financial intermediation.

Addressing these structural debt issues is crucial for achieving China’s stated economic transition goals and maintaining long-term financial stability.

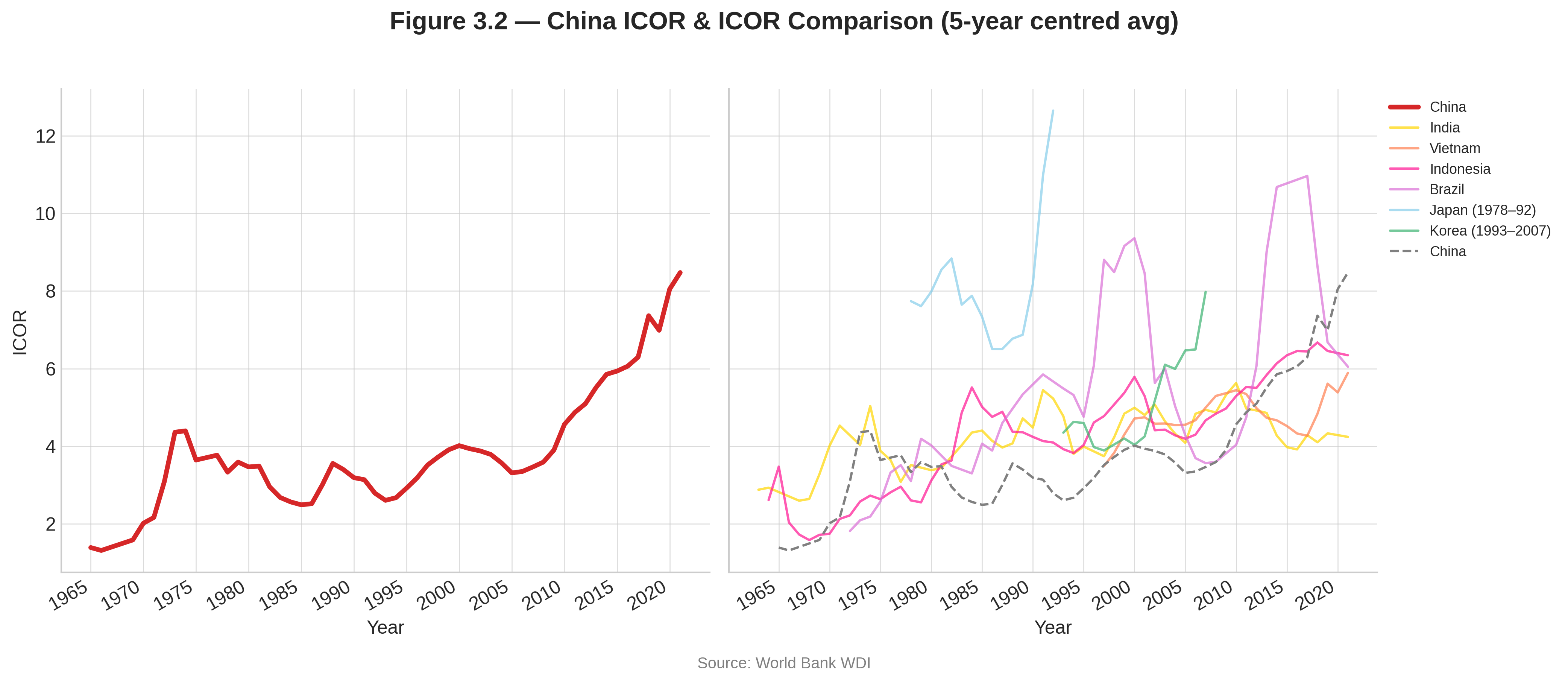

Critically, this explosive growth in credit has coincided with increasingly clear signs of diminishing returns on investment. A key metric illustrating this trend is the Incremental Capital-Output Ratio (ICOR), which measures the amount of additional capital investment required to generate one additional unit of GDP growth. A rising ICOR signals falling investment efficiency. In China’s case, the ICOR has deteriorated markedly. While in the early 2000s, an estimated 3-4 yuan of new investment might have generated 1 yuan of additional GDP growth, by the late 2010s and early 2020s, this figure had climbed towards 6-8 yuan or even higher according to some analyses. This indicates that the vast sums invested, particularly in infrastructure and real estate post-GFC, are becoming progressively less productive in driving economic expansion. Capital is being allocated to projects with lower marginal returns, fueling concerns about resource misallocation and exacerbating debt sustainability challenges. This declining efficiency directly undermines the viability of the old growth model and highlights the urgent need to shift towards more productive growth drivers.

Data Box 3.2:Reading China’s ICOR: Investment Efficiency and Economic Implications

The Incremental Capital-Output Ratio (ICOR) measures the efficiency of investment by showing how many percentage points of GDP invested are needed to generate one additional percentage point of real GDP growth. ICOR is critical for understanding China’s economic trajectory, debt dynamics, and rebalancing efforts.

ICOR = (Gross fixed capital formation % GDP) / Real GDP growth %

1. Interpreting ICOR

- Optimal ICOR (≈3–4): Typical in rapidly growing, developing economies; indicates efficient capital utilization and high economic returns.

- Rising ICOR: Suggests declining capital productivity, signaling that each additional unit of investment yields progressively lower economic growth, often associated with inefficient, debt-driven projects.

- High-Income Economies: With lower investment shares and modest growth, ICOR fluctuates widely, driven primarily by small changes in growth rates rather than genuine investment efficiency.

- Comparative Caution: ICOR comparisons are most insightful when economies share similar development stages and investment intensity.

2. Selected Comparative Benchmarks

Source: World Bank WDI (NE.GDI.FTOT.ZS and NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG). Data smoothed with five-year centred averages; extreme ICOR values capped at 20 for clarity.

| Economy | Relevance for China’s Economic Analysis |

|---|---|

| India, Vietnam, Indonesia, Brazil | These economies currently have investment rates (25–35% GDP) similar to China, offering valuable contemporary benchmarks for efficient and inefficient capital use. |

| Japan (1978–92), Korea (1993–2007) | Early portions of these periods closely match China’s current per capita income (~USD 17–20k in 2017 PPP) and high investment levels, illustrating ICOR trends before encountering diminishing returns. |

| Current G-7 Economies | Excluded due to low investment shares and modest growth rates, rendering ICOR less meaningful in measuring investment efficiency. |

3. Key Findings from ICOR Trends (Figure 3.2)

- China’s Rising ICOR: China’s ICOR increased significantly from approximately 3.5 in the early 2000s to around 8 today, clearly signaling diminishing returns and reduced capital efficiency.

- Peer Comparisons: India and Vietnam maintain relatively stable ICOR values (around 4–5), while Indonesia and Brazil hover around 6, underscoring China’s notably sharper deterioration.

- Historical Benchmarks: Japan and Korea reached ICOR values around 6–7 just before significant slowdowns in growth and reductions in investment rates. China now faces similar efficiency pressures but maintains nearly double their historical investment shares.

4. Economic Implications of High ICOR

- Debt Intensification: With an ICOR of about 8, sustaining a 5% GDP growth rate requires investment levels around 40% of GDP annually, fueling continued debt accumulation as detailed in Box 3.1.

- Crowding Out Consumption: Persistent high and inefficient investment allocation towards state-driven projects limits resources available for household income growth and private consumption, directly hindering economic rebalancing.

- Reduced Policy Options: Maintaining current growth levels under high ICOR conditions necessitates further increases in debt-driven investment or substantial productivity enhancements, both challenging under existing economic policies.

China’s elevated ICOR underscores its transition from a high-efficiency growth economy to one increasingly burdened by inefficient capital allocation and debt dynamics. Policy efforts must focus on significantly improving investment productivity, restructuring state-directed investments, reforming land-financing mechanisms, and realigning resources to support household incomes and consumption-driven growth.

A significant portion of this problematic debt is concentrated within opaque structures linked to local governments, primarily Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs). Historically prevented from borrowing directly to fund their extensive expenditure responsibilities (especially after the 1994 fiscal reforms centralized revenues but not spending obligations), local governments established thousands of LGFVs. These corporate entities borrowed heavily from banks and bond markets, often using land assets as collateral, to finance vast infrastructure projects, especially after 2008. Because this debt was technically corporate, it remained “off-balance-sheet” for local governments, obscuring the true extent of public sector liabilities. Estimates of LGFV debt are enormous, with the IMF’s calculation of “augmented” government debt (including these liabilities) reaching an estimated 110-120% of GDP by 2023, far exceeding official general government debt figures. Many LGFV-funded projects, particularly in less developed regions, do not generate sufficient revenue to service their debts, leading to a reliance on refinancing, land sales (a now diminishing revenue source), or implicit state support. This creates substantial contingent liabilities and constrains local fiscal capacity, diverting funds from essential public services that are crucial for boosting household security and, by extension, consumption.

Parallel to LGFV liabilities, the property sector became another major nexus of leverage and systemic risk. Developers, fueled by easy credit (including from shadow banking channels and offshore borrowing) and expectations of perennially rising prices, accumulated vast debts. The implementation of the “Three Red Lines” policy by regulators in 2020-2021, aimed at deleveraging highly indebted developers, triggered a cascade of defaults, most notably affecting giants like Evergrande. This ongoing property sector downturn has profound negative ramifications: it slashes construction-related investment, erodes household wealth and confidence (thereby dampening consumption, as discussed in Chapter 2), damages the balance sheets of exposed financial institutions, and cripples local government finances by curtailing land sale revenues, which were vital for servicing LGFV debts. The deep interconnectedness of property debt with the broader financial system and local government solvency makes its resolution exceptionally complex and pivotal for economic stability.

Definition Box 3.1: China’s “Three Red Lines” for Property Developers

Introduced in August 2020, China’s “Three Red Lines” policy sets clear financial benchmarks to constrain excessive leverage among real estate developers, thereby mitigating systemic financial risks in the property sector.

| Metric (excluding presale deposits) | Red Line | Policy Intent |

|---|---|---|

| Liabilities ÷ Assets | ≤ 70% | Cap overall leverage |

| Net gearing (Debt ÷ Equity) | ≤ 100% | Limit debt-driven land acquisition |

| Cash ÷ Short-term debt | ≥ 1× | Ensure adequate liquidity for at least 12 months |

Traffic-light system (August 2020):

- 0 breaches: Debt can increase up to 15% annually.

- 1 breach: Debt can increase up to 10% annually.

- 2 breaches: Debt can increase up to 5% annually.

- 3 breaches: Debt growth halted entirely.

Policy Objectives:

- Discourage speculative borrowing and reduce financial sector risk.

- Reinforce the guiding principle: “houses are for living in, not for speculation.”

Immediate Impacts (2021–2023):

- Approximately two-thirds of China’s top-30 developers breached at least one red line within the policy’s first year, significantly restricting their access to bond markets.

- Local governments experienced a 23% decline in land-sale revenue in 2022, compounding financial stress on Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs) highlighted in Box 3.1.

- Prominent developer defaults (Evergrande, Kaisa, Sunac) stalled projects, eroded homebuyer confidence, and triggered a broad credit contraction across the real estate sector.

Funding Channels and Associated Risks:

| Channel | Description | Risks |

|---|---|---|

| Shadow Banking | Trust loans and wealth-management products not listed formally | High interest, low transparency, shifts risks to households and small financial institutions |

| Offshore USD Bonds | Bonds issued via offshore (e.g., Cayman Islands) entities | Foreign-exchange mismatches, weak investor protections; defaults abroad quickly undermined domestic market confidence |

The “Three Red Lines” policy exposed previously hidden leverage levels and abruptly restricted developers’ access to easy credit. Although this transparency was essential for financial stability, the sudden withdrawal of credit precipitated severe stress that quickly extended beyond developers—affecting banks, households, and LGFVs. This interplay amplified the broader debt challenges discussed throughout Chapter 3.

Collectively, this enormous debt overhang—spanning LGFVs, the property sector, and parts of the non-financial corporate sector (especially some SOEs)—acts as a significant drag on China’s economy and severely constrains policy options for rebalancing. High debt levels necessitate cautious monetary policy to avoid exacerbating financial instability. They limit the fiscal space for substantial stimulus aimed at boosting household consumption or social welfare, as resources may be preempted by the need for potential bailouts or debt restructuring operations. Furthermore, the prevalence of “zombie” firms (indebted, unproductive entities kept afloat by rolling over loans) and non-performing assets locks up capital and labor that could otherwise be reallocated to more dynamic and innovative sectors, thereby hindering overall productivity growth. Effectively managing this debt legacy, which involves difficult choices about restructuring, addressing moral hazard, and reforming the underlying governance of local finance and state-linked investment, is therefore an indispensable prerequisite for China to successfully transition towards a more balanced, efficient, and sustainable growth trajectory. Failure to do so risks either protracted stagnation under the weight of existing liabilities or a more acute financial crisis that could abruptly derail its rebalancing ambitions and long-term development. This sets the stage for understanding the role of state-controlled entities and resource allocation, which is the focus of Chapter 4.

4. The State’s Shadow: SOE Dominance, Resource Misallocation, and Stifled Dynamism

How does the persistent dominance of State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) and state-directed resource allocation stifle the private sector dynamism crucial for a consumption- and innovation-led economy?

The legacy of debt and diminishing returns on investment, as explored in Chapter 3, casts a long shadow over China’s rebalancing efforts. Compounding these challenges is the enduring and pervasive influence of the state itself in directing economic activity. While China’s economic miracle since 1978 has been characterized by the rise of a vibrant private sector, the Party-state continues to exert profound control over the economy’s “commanding heights” through its State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) and its overarching influence on resource allocation. This “State’s Shadow” creates significant structural distortions, systematically misallocating capital, stifling private sector dynamism, and hindering the development of a truly market-driven innovation ecosystem. These factors act as formidable barriers to achieving a more balanced, efficient, and consumption-oriented economic structure, revealing the deep-seated political economy constraints at the heart of China’s rebalancing paradox.

Despite decades of market reforms, SOEs maintain a dominant presence in strategically critical and capital-intensive upstream sectors, including energy, telecommunications, banking and finance, heavy industry, transportation, and critical resources. While their direct share of GDP (often estimated around 25-30%) may be less than that of the private sector, their systemic importance is magnified by their control over essential inputs and infrastructure, and most crucially, by their preferential access to national resources, particularly financial capital. The state-dominated banking system has consistently channeled a disproportionate share of lending towards SOEs and other state-affiliated entities. This occurs not always due to superior commercial merit but often because of implicit state guarantees (reducing perceived default risk for lenders), policy-driven lending mandates, and established political connections.

Data Box 4.1: China’s Preferential Credit Allocation to SOEs vs. Private Firms

This box clarifies the structural bias in China’s bank credit allocation toward State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) compared to private enterprises and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), highlighting its economic implications.

Credit Allocation: SOEs vs. Private Firms

| Metric | SOEs | Private Firms (+ SMEs) |

|---|---|---|

| Share of corporate loans | ≈ 45–55% | ≈ 45–55% |

| Share of national GDP | ≈ 25–30% | ≈ 70–75% |

| Share of urban employment | ≈ 13–17% | ≈ 83–87% |

| Average borrowing rate (2023) | ≈ 3.9% | ≈ 4.8% |

What These Numbers Reveal:

- Credit mismatch: SOEs obtain roughly half of all corporate bank loans while generating only about a quarter of China’s GDP and employing fewer than one-fifth of urban workers, indicating significant structural misallocation.

- Cost differential: SOEs consistently enjoy lower interest rates—approximately 1 percentage point lower—compared to private enterprises. This discrepancy provides SOEs with a major competitive advantage, distorting market dynamics.

- Efficiency gap: According to academic and IMF analyses, SOEs typically achieve returns on assets (ROA) of just 2–4%, significantly lower than the 6–8% ROA typical of private firms. Cheap financing thus perpetuates lower-yielding investments.

Sectoral Considerations:

SOEs dominate capital-intensive sectors such as utilities, energy, and transportation, which partially justifies their substantial credit share. Nonetheless, even within these sectors, private firms consistently demonstrate superior productivity and profitability. Preferential financing terms and implicit state backing enable SOEs to outcompete private firms for scarce credit, entrenching capital in lower-yield, less efficient projects.

Implications for Economic Rebalancing:

Persistent credit allocation bias toward SOEs directs capital away from more efficient, higher-return private enterprises, thereby weakening productivity growth and limiting household income growth. These distortions undermine China’s broader objectives of shifting toward a consumption-driven economy, as discussed throughout Chapter 4.

Sources: People’s Bank of China (2023), World Bank China Economic Update (2022), National Bureau of Statistics, Peterson Institute for International Economics (Lardy, 2021), PBoC Financial Statistics (2023).

This systematic bias in resource allocation has several profound and detrimental consequences for the broader economy and the rebalancing agenda:

- Capital Misallocation and Lowered Efficiency: The flow of cheap and abundant credit to SOEs, which often exhibit lower productivity and returns on assets compared to their private sector counterparts, leads to significant capital misallocation. Resources that could have fueled more dynamic and innovative private enterprises are instead locked into often less efficient state-controlled entities. This not only depresses overall economic efficiency and curtails potential GDP growth but also reinforces the investment-led model, as SOEs are frequently the primary vehicles for state-directed, large-scale capital expenditure, often with objectives beyond pure commercial viability.

- Stifled Private Sector Dynamism and Competition: Preferential treatment for SOEs inherently disadvantages private firms, particularly Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs), which are crucial for job creation, innovation, and broadening the base for household income growth. Facing higher borrowing costs, restricted access to finance, and sometimes regulatory hurdles designed to protect SOE market share (entry barriers), private companies are “crowded out.” This can deter private investment, slow the scaling of innovative startups, and limit the competitive pressures that drive efficiency and consumer-centric innovation. While China boasts globally successful private tech giants, the broader landscape for many smaller or non-strategic private firms remains challenging.

- Hindrance to Consumption-Led Rebalancing: The dominance of SOEs and their operational priorities directly impact the shift towards consumption. SOEs typically retain a larger share of their earnings for reinvestment (often aligned with state strategic goals) or transfer them to the state, rather than distributing them more broadly as wages or dividends that would boost household income and consumption. Moreover, by channeling capital towards capital-intensive projects, the system perpetuates an economic structure that favors returns on capital over broad-based growth in labor income, which is foundational for a consumption-driven economy. The development of a robust, labor-intensive service sector—key for job creation and widespread income distribution—can also be constrained if investment and policy focus remain skewed towards state-led heavy industry or infrastructure.

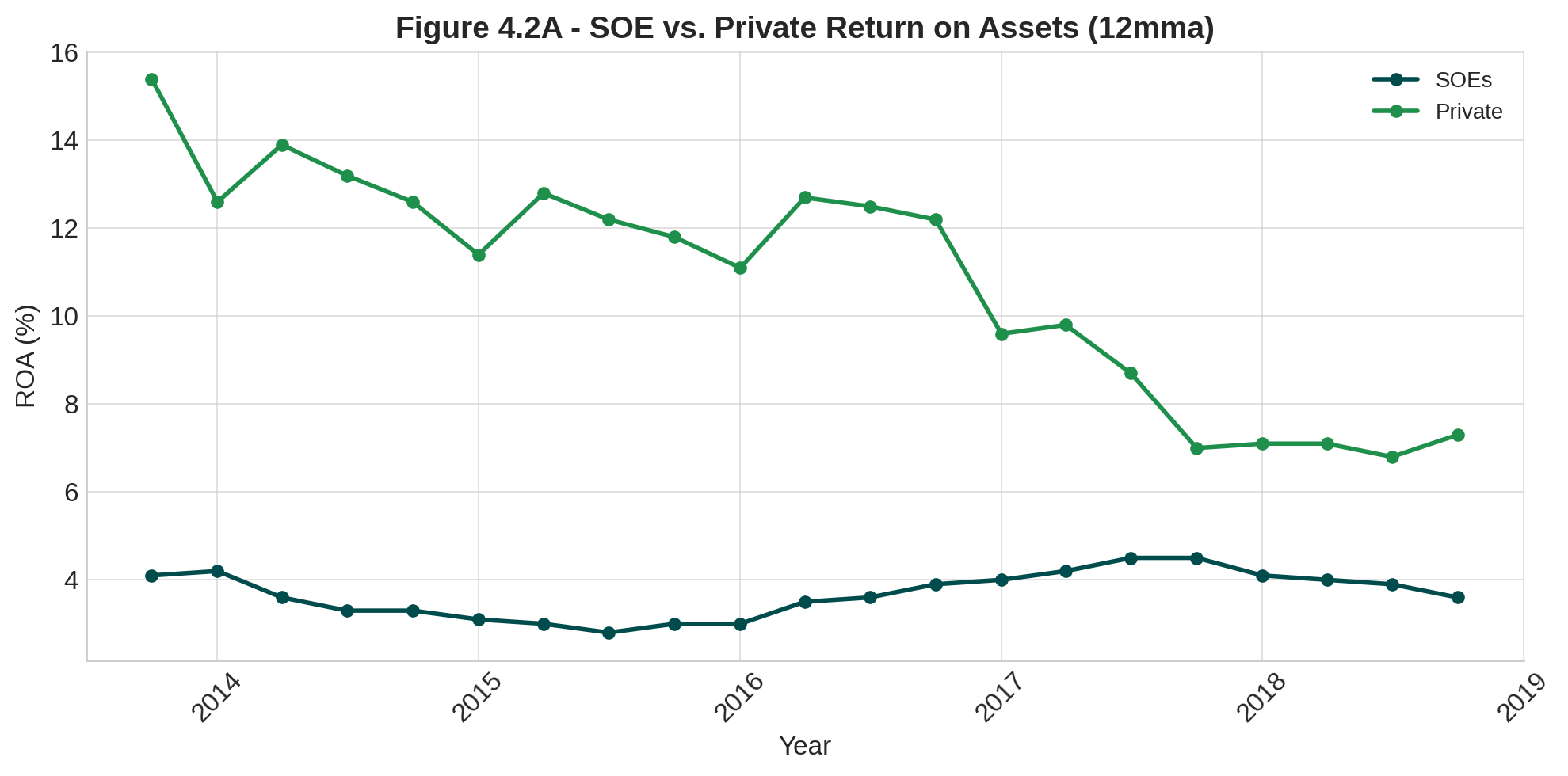

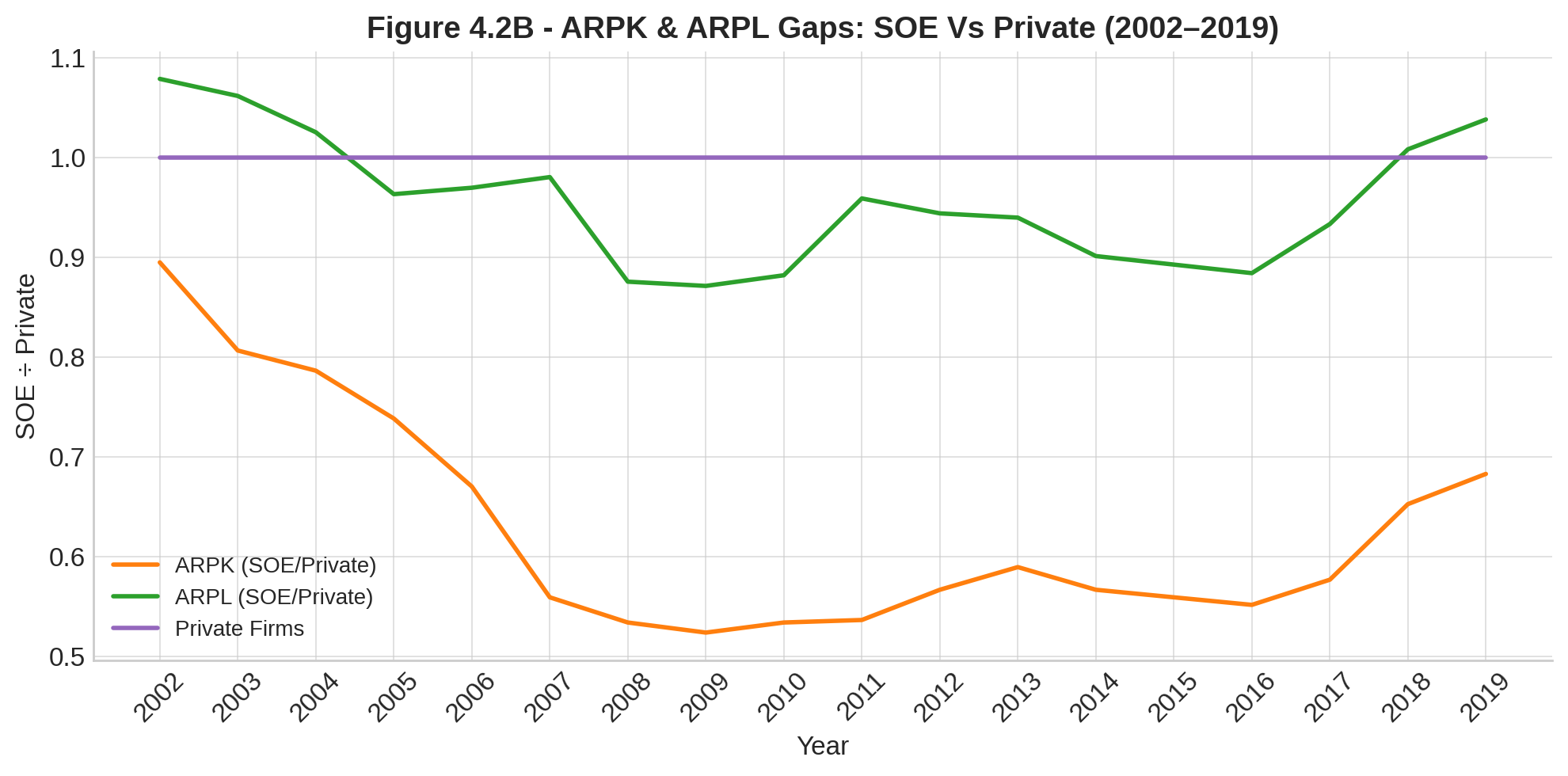

Data Box 4.2: The Productivity Gap: SOEs vs. Private Enterprises

This box quantifies the productivity and profitability differences between China’s State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) and private enterprises, highlighting structural inefficiencies resulting from preferential credit allocation.

Figure 4.2A — Return on Assets (ROA)

(12-month moving average, 2014-Q3 to 2019-Q3)

- SOEs: Stable at approximately 3.5–4%.

- Private Firms: Declined from around 15% to about 7%.

(Source: Asia Society “China Dashboard,” based on NBS data, Rhodium Group.)

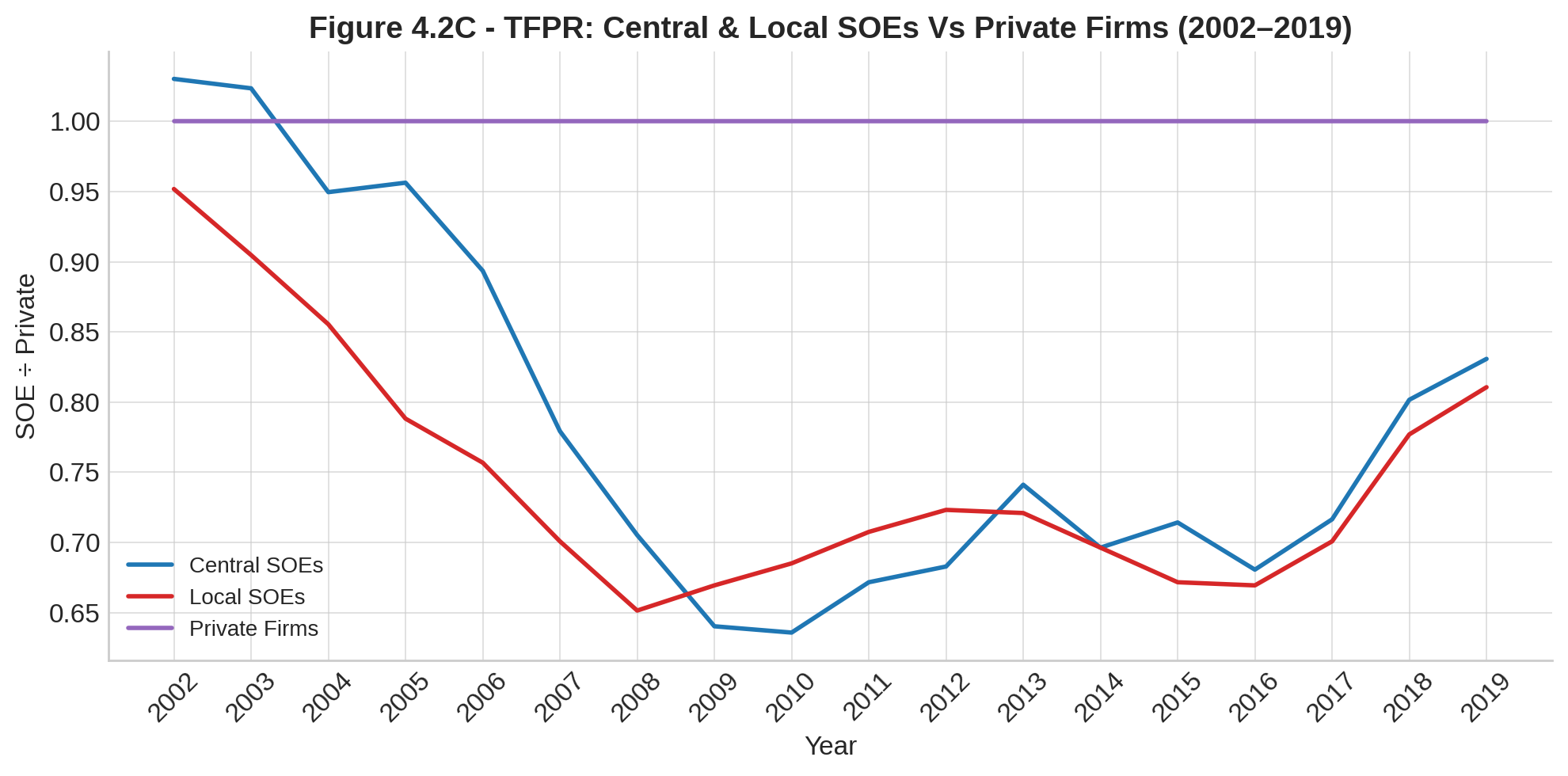

Figures 4.2B – 4.2C — Productivity Ratios (SOE ÷ Private Firms)

(Listed firms, 2002–2019; parity = 1.0)

- Capital Productivity (ARPK): Dropped to approximately 0.6 in 2009, recovering to around 0.8 by 2019.

- Labour Productivity (ARPL): Consistently around 0.85–0.95.

- Total Factor Productivity (TFPR): Fell to about 0.65 in 2009, improved to around 0.84 by 2019.

(Source: IMF WP 21/75.)

Key Metrics Explained:

| Metric | Meaning | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| ARPK | Revenue per unit of capital invested | Efficiency in using capital |

| ARPL | Revenue per employee | Efficiency in labour utilization |

| TFPR | Combined capital and labour efficiency | Overall productivity and resource allocation efficiency |

Key Findings:

- Capital inefficiency: SOEs consistently generate only 60–80% of the revenue per unit of capital compared to private firms, particularly since the 2008 global financial crisis. This gap underscores persistent inefficiencies in capital allocation.

- Labour inefficiency: SOEs maintain roughly 10–15% lower revenue per employee compared to private enterprises. Even considering the more capital-intensive nature of typical SOE sectors, this persistent gap indicates fundamental managerial and operational inefficiencies.

- Overall productivity shortfall (TFPR): Accounting for both capital and labour inputs, SOEs’ total productivity remains approximately 15–35% below that of private firms. Such a significant and persistent gap demonstrates chronic resource misallocation in the state-dominated sector.

- Return on Assets (ROA): By 2019, SOEs achieved an average ROA of just 3.6%, roughly half the 7.3% ROA earned by private firms. Despite preferential access to lower-cost credit (as detailed in Box 4.1), SOEs consistently fail to translate these financial advantages into efficient and profitable outcomes.

Sectoral Considerations:

IMF analyses adjusting for detailed industry classifications confirm these productivity gaps persist even within the same sectors. This suggests systemic factors—such as soft budget constraints, politically driven investment priorities, and implicit state backing—significantly contribute to lower SOE efficiency beyond mere sectoral differences.

Bottom Line:

China’s continued preferential credit allocation toward lower-efficiency SOEs materially reduces overall economic productivity and efficiency. Until capital and resources are more equitably allocated toward higher-return investments, China’s economy will remain heavily reliant on debt-driven growth, thereby impeding the crucial transition towards a more balanced, innovative, and consumption-led economic model.

The challenge is further compounded by regulatory cycles and the overarching emphasis on Party control. Particularly since the late 2010s, a series of regulatory interventions targeting influential private sector domains—notably internet platforms, fintech, and private education—while often justified by legitimate concerns such as curbing monopolistic practices, enhancing financial stability, or promoting “common prosperity,” have also introduced significant policy uncertainty. The abruptness and perceived unpredictability of these crackdowns have had a palpable chilling effect on private sector risk appetite, dampening investment and innovation in key growth areas. While Beijing has subsequently issued rhetoric aimed at reassuring private enterprise, the underlying message of the Party’s ultimate supremacy and its readiness to intervene decisively creates a cautious environment for entrepreneurs.

This persistent state-market imbalance is deeply embedded in China’s political economy. SOEs serve crucial political and social functions for the Chinese Communist Party: they ensure state control over strategic sectors, provide a degree of employment stability (even if inefficiently), act as direct instruments for policy implementation (e.g., undertaking counter-cyclical investment or strategic national projects), and form part of the Party’s extensive patronage network. Consequently, fundamental reforms that would genuinely level the playing field—such as imposing hard budget constraints on SOEs, allowing market-based defaults for failing state firms, comprehensively breaking up state monopolies, or ensuring truly competitively neutral access to credit—often encounter strong resistance from vested interests and challenge the Party’s established levers of economic stewardship. As a result, SOE reforms in the post-GFC era have frequently prioritized consolidation (making SOEs “bigger and stronger”) and the reinforcement of Party leadership within these enterprises, rather than thorough marketization or privatization that might enhance overall economic efficiency but could diminish direct state influence. This reveals a fundamental trade-off the leadership continually navigates: the desire for economic dynamism versus the non-negotiable imperative of maintaining Party control.

The existence of highly successful private “national champions” (like Huawei, Alibaba, Tencent, BYD, CATL) operating in strategic sectors seems to contradict the narrative of a stifled private sector. However, their success often highlights a more nuanced reality: these firms frequently thrived by aligning with national strategic goals, benefiting from targeted (sometimes indirect) state support, accessing alternative financing channels (like international venture capital or stock listings in their growth phases), and demonstrating exceptional innovation and execution. Their success can be seen as the Party-state leveraging private dynamism for specific strategic ends, rather than indicative of a universally level playing field. Even these champions have faced increased regulatory scrutiny, underscoring the Party’s ultimate authority. This complex interplay between state objectives and private sector prowess underscores the unique, and often paradoxical, nature of China’s state-capitalist model. The dilemma for Beijing is whether the exceptionalism of these few champions can be broadened to the entire private sector to truly drive rebalancing, and to what extent this is possible without conceding levels of economic autonomy that might challenge the Party’s preferred model of governance.

Data Box 4.3: Control vs. Dynamism: China’s SOE Reform since 2013

This box highlights the core tension in China’s ongoing State-Owned Enterprise (SOE) reforms, which seek to enhance commercial efficiency and innovation while reinforcing strategic oversight by the Party-state.

1. Key SOE Reform Milestones (2013–2023)

| Period | Reform Initiative | Efficiency Objectives | Party-State Oversight |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013–15 | Mixed-Ownership Reform Pilots | Introduce private capital and improve market discipline and governance. | State retains controlling stakes; internal Party committees maintain strategic decision-making authority. |

| 2015–17 | “Bigger & Stronger” SOE Consolidations (e.g., Baosteel-Wuhan merger) | Realize economies of scale, reduce overcapacity and duplication. | SASAC guides mergers and oversees executive appointments to ensure alignment with state objectives. |

| 2018 | Enhanced Party Role in Corporate Governance | Strengthen accountability and align corporate strategies with Party goals. | Formal integration of Party Committees into corporate governance structures; major decisions require Party approval. |

| 2020–21 | Bond Defaults & Financial Discipline | Enforce fiscal responsibility, phasing out persistently unprofitable SOEs. | Strategic SOEs maintain implicit state guarantees; selective bailouts continue. |

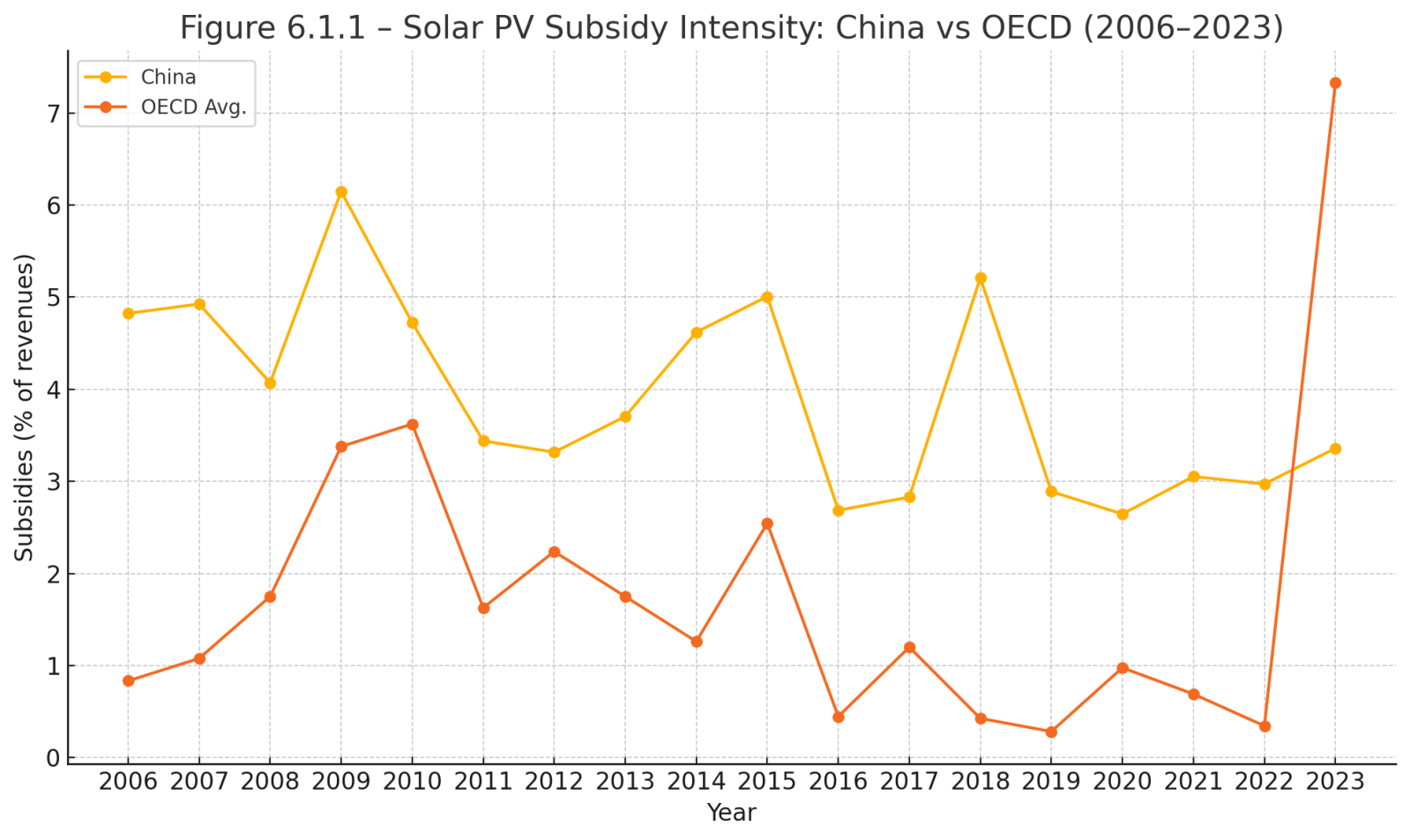

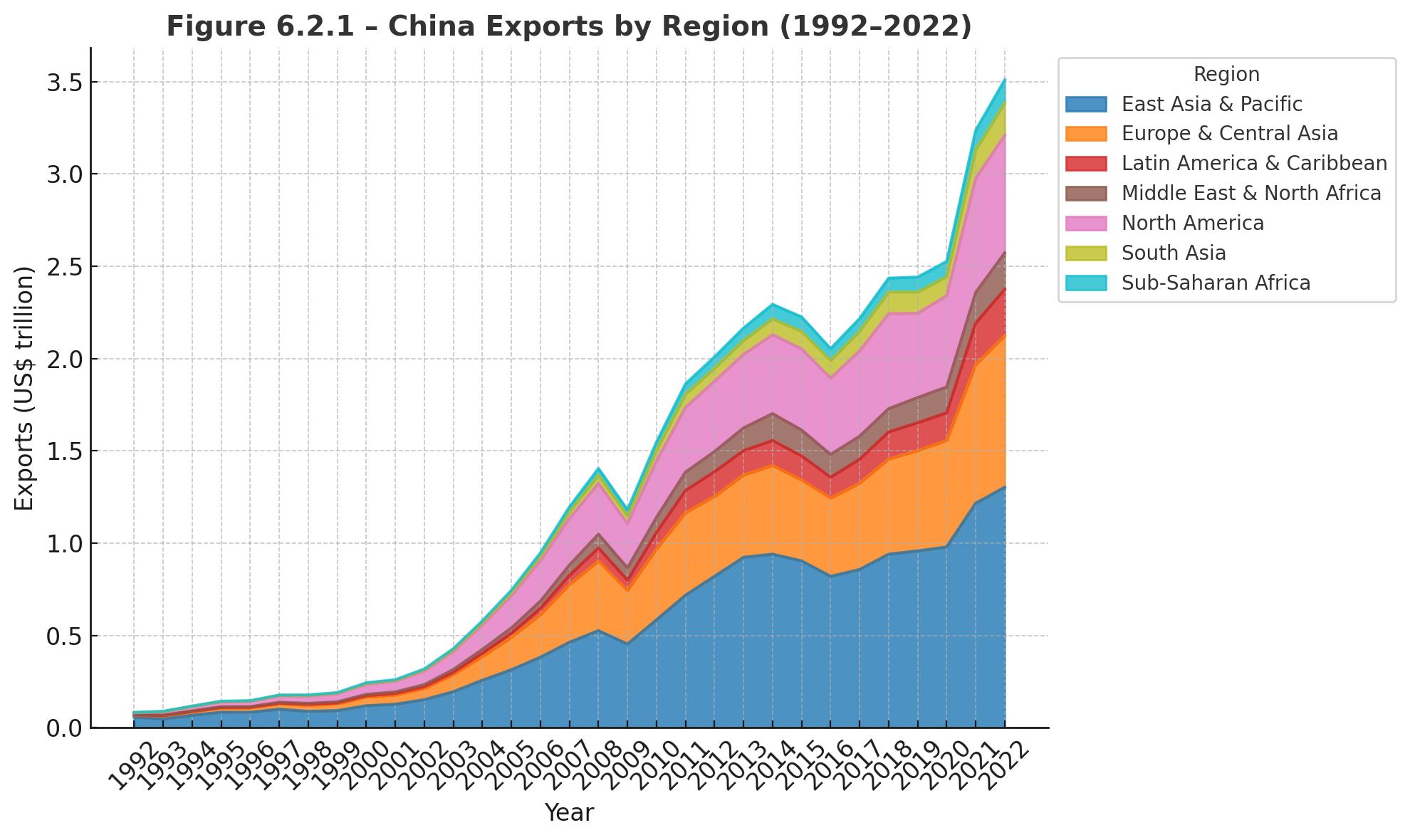

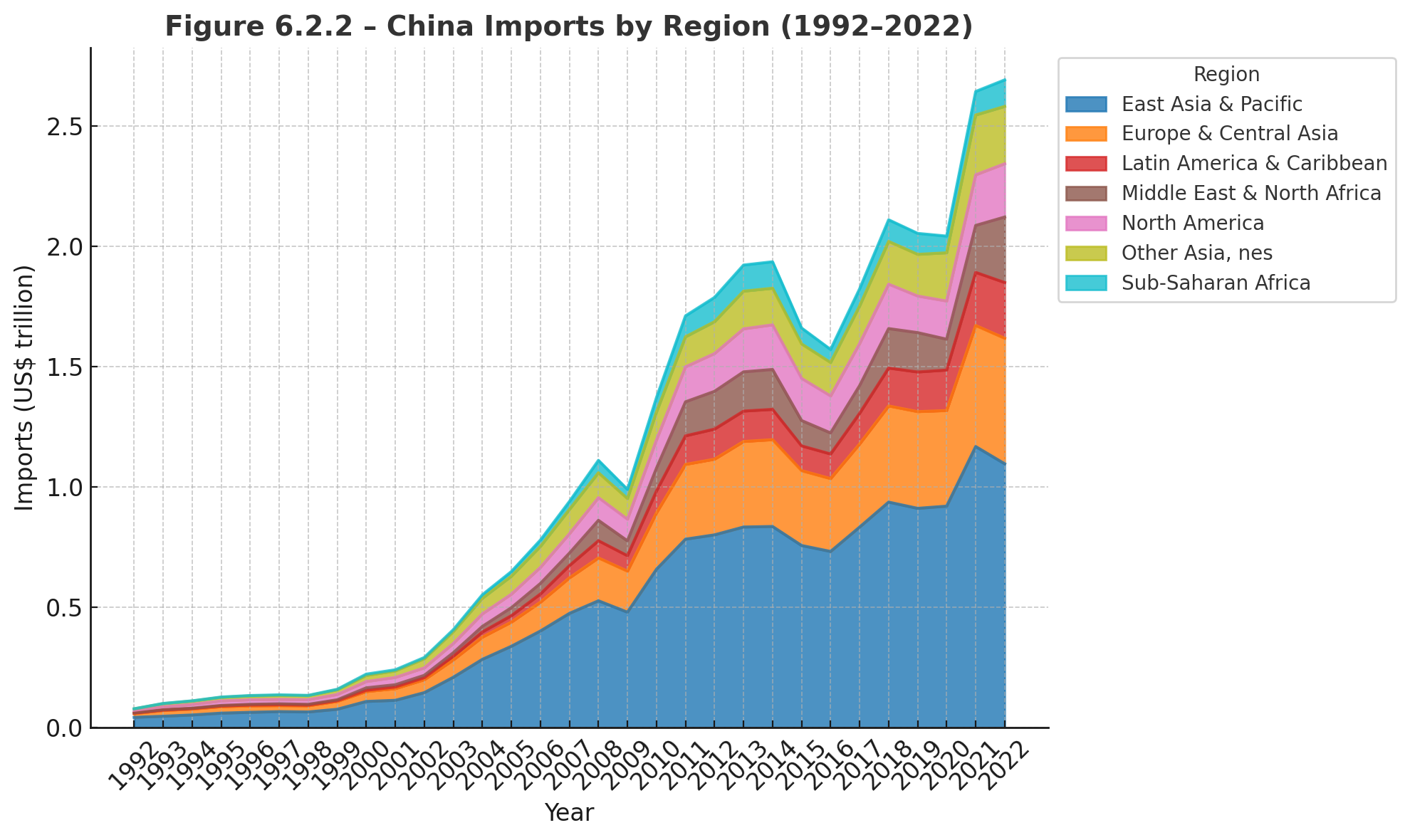

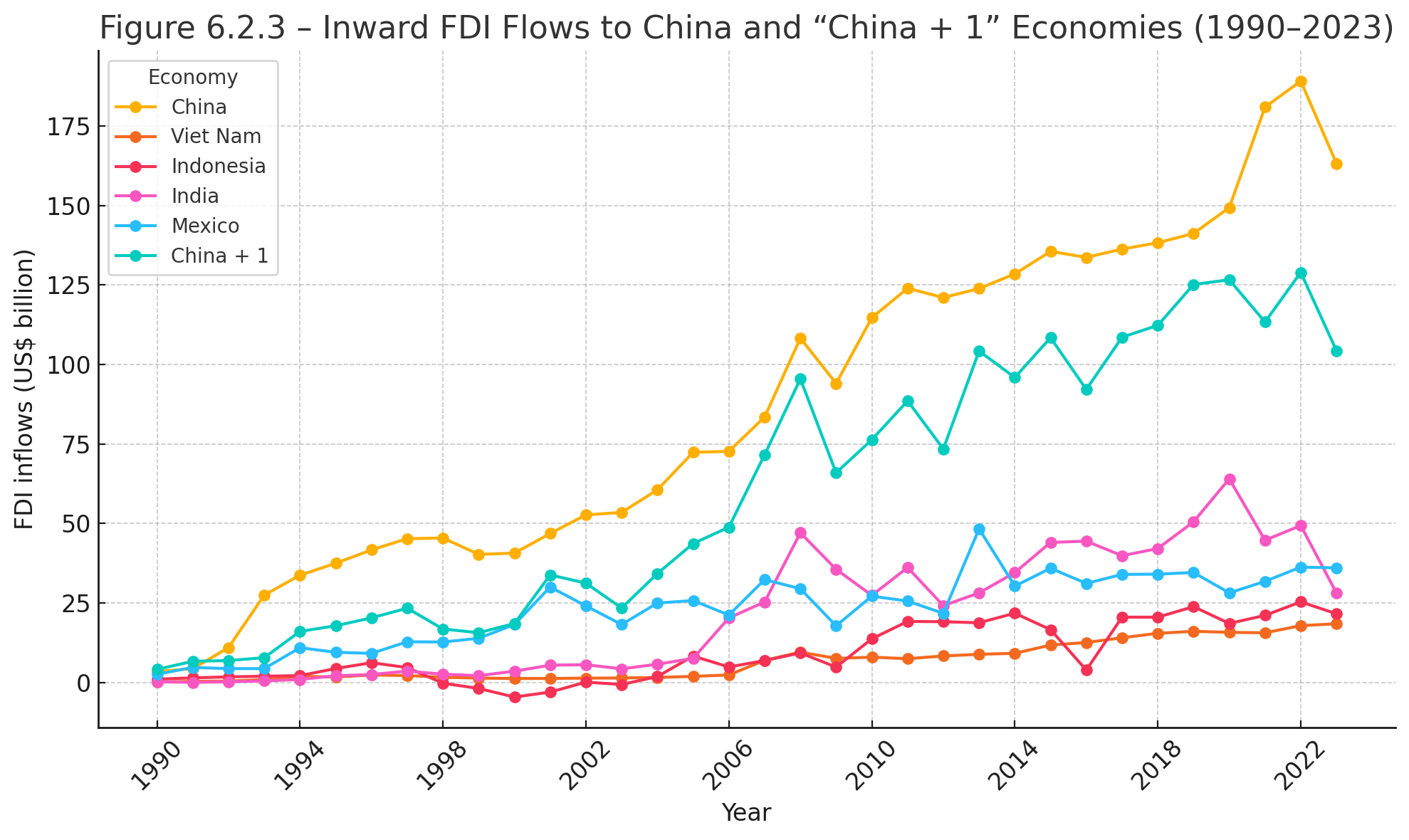

| 2021–23 | Regulatory Crackdowns (Ant, Didi, Big-Tech fines) | Manage financial risks and ensure private-sector alignment with national security. | Tightened Party oversight over private sector activities, emphasizing strategic control over market-driven expansion. |